Seven Beauties is an Italian movie from 1975 with which I was heretofore unfamiliar. It was directed by Lina Wertmuller, of whom I guess I had heard, but I did not know anything about her. I had assumed she was German, to begin with (she is of aristocratic Swiss descent, but was born, and as far as I can tell primarily grew up, in Rome). Since she seemed to be admired exclusively by either self-serious intellectuals or the most impossibly with-it people, while I was aware of no humbler or duller person who had any familiarity with her work, I had a vague idea that she operated as a director on the more difficult and inaccessible end of the German New Wave. This did not deter my excitement to try to take it on, for I often like movies of this type, though I harbored little realistic hope that I would be able to understand most of what was important about it. And while my taste very often does not agree with what hip and edgy people find worth their time, I usually can find something that is appealing to me in things that real intellectuals like, even if I don't understand them. This may appear a paradox or impossibility, and I suppose it is if one admits that nothing has reality that fails to meet the most basic laws of logic; however it is clear much of conscious life, both of the social and inner varieties, takes place outside of these narrow bounds.

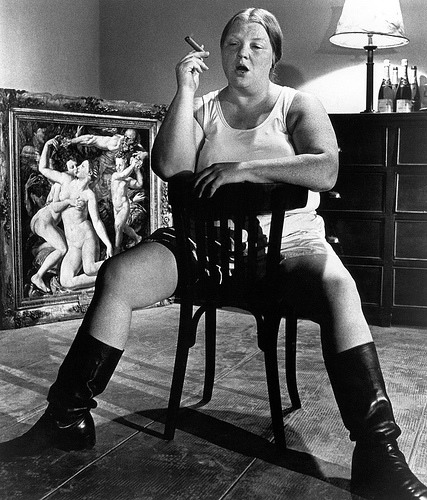

Seemingly everyone who writes about Seven Beauties concurs that it is outstanding, a film of the very first rank all around. I will only join in with this chorus because I do not think this enthusiasm and high opinion have penetrated very far even among the general intelligent cinephile public. In the course of this movie several hundred people are killed by firing squads, the body of a murdered man is chopped up and packed into three separate suitcases and put on three separate trains, a man in a concentration camp contrives his end by diving into a sewage pit and refusing to come up again (though the guards unload a few dozen rounds of machine gun fire into the pit just to be sure), there are a sex scene involving a sadistic 250 pound female prison guard in an office whose furnishings include a swastika rug and an enormous photograph of Hitler, a rape of a woman tied up in a bed in an insane asylum, and some of the ugliest women (contra the title) ever seen in any movie anywhere, as well as one of the clearer representations of the kinds of things a person in a concentration camp could be brought to do that I have seen, at least in a long time. Yet it is in many instances comic, at least in an absurd way. It is also serious, but the interjections of comedy and absurdity insist that this seriousness is no way the result of straining or conscientiousness. The tone and the balance of this mass of horrors juxtaposed with the underlying absurdity and the occasional flash of intelligent or pertinent observation ('How did the world get like this?") is achieved about as perfectly as could have been expected (and it had to be). It is the signature accomplishment here.

Fernando Rey is in this. It is always a delight to see him, even though here it is as a prisoner in a concentration camp. His presence had not been advertised in the brief promotional and critical summaries I had come across, and it is a rather small role. However his whole persona as an actor, especially in this period, is largely of the same animating spirit as that prevalent throughout this movie, so it is almost as if he is there for emphasis (Look! It's Fernando Rey! And he is in a striped concentration camp outfit! And he is still suave and witty and contemptuous! And you love it!)

The star was Giancarlo Giannini, whom I have not seen before. He is most famous for his parts in Lina Wertmuller movies. His performance stands out, enough that he was nominated for the regular best actor Oscar for the 1976 awards despite his movie's obviously being in a foreign language (which is not as rare of an occurrence as I thought, however). Lina Wertmuller was nominated for best director as well, which indicates to me that the film made a splash of some kind at the time. I wonder why it has become relatively forgotten. Besides still being very good, the basic story is not difficult to follow and while entertaining is not exactly the word I would use to describe it because of the nature of the content, its construction and the way it unfolds is in what I would call the entertaining style (that is, the story is always active, each little section builds up to a climax, these occur at intervals that are not too far apart, and the result hurtles you forcefully into the next scene).

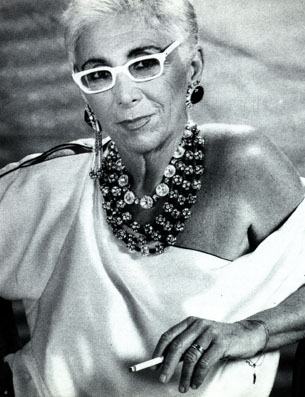

Lina Wertmuller's Oscar nomination for this was the first ever for a female director. I feel like I am supposed to be overcome by trepidation and discomfort as a result of this, but as long as the direction isn't cloying or reveling in opposition to everything our male-centric traditions and civilization hold dear, which is not blatantly the case here, I don't see why I would be. Wertmuller looks to be one of those old European artist-intellectual types who always hung with the big brain boys and knows, and mainly cares about, what is and has been in the past strong and worthy in the arts and thought, who is not motivated by personal animosities or resentments or extreme self-absorption, and who finds interesting stories and things to think and write about outside of this, which is always a rare ability no matter who the group is made up of.

The opening sequence included some film footage of Hitler and Mussolini. We all know what Hitler looks like, but I had never seen much tape on Mussolini. He was really absurd.

There was an interview with Lina Wertmuller in the extras that came with the movie. It was over an hour long so I did not watch much of it, but there was one minor, prosaic item in it that caught my attention. Wertmuller's father was an important lawyer in Rome, and his idea, which he did not neglect to plant in her head, had been that she would be one too. This made an impression on me because I have noticed people are starting to ask my older two sons what they want to be when they grow up, and invariably they say "I don't know". I am sure this is an honest reply, and that they have no idea what they would like to do, because the serious work world that the people who are asking these questions have in mind can hardly have much reality for my children, mainly because it is does not have much for me. There is an immortal line in the old movie Dead Poet's Society where a heartless father barks to his son, who is overindulging in the romantic side of his personality at his exclusive boarding school, "You're going to Harvard, and you're going to be a doctor". This line has always stuck with me, because it not only sets a clear bar of what is the minimum that will be acceptable for the child going forward, but that the parent knows absolutely what he is saying, and that it is easily within his power to bring about the desired result if the child has the least capacity and will to attain it. A more humbly placed family cannot in most instances insist that their children get into and attend elite colleges and become doctors, because they simply don't have the knowledge of what is actually required to achieve those goals. Of course lower class families have pride and set bars as well--even at the bottom, Chris Rock's famous joke about keeping your daughter off the pole applies--but in the case of Lina Wertmuller and many other writers and other creative people that one reads about, even if there is some flexibility with regard to the ultimate occupation, the message was clear that anything below the education level and respectability of 'lawyer' was essentially the equivalent of 'the pole', and was not to be considered as acceptable, ever. People who come from this kind of background of expected success are not wholly conscious of this, because it is the very atmosphere they breathe; but it is real, and powerful.

But to return to my children: Where we live there are a lot of Libertarian types, people who hate taxes and worship capitalism, and due to choices we have made with regard to schools and activities in addition to the relative density of their numbers locally, we are coming into contact with them with increasing frequency. These people don't quite know what to make of me, which is understandable, as I don't know what to make of myself, but they see that my wife is an energetic and extremely resourceful person who never whines about fate or limitations or not being able to do something she wants to do, but immediately and constantly sets to making plans for how her various desires might be brought about (I would tell you some of these successful and to me marvelous schemes, but I don't think she would like being brought alive as a character in this blog to that extent) and that my sons are not complete blockheads either in academics or in practical matters, and seem to be doing at least as well as their own children, in spite of their comparatively lackluster paternal guidance and example. I have noticed a couple of times now people not only asking the two older ones what they wanted to be when they grew up, but whether they had chores at home or not, and indeed one person asked them whether they were aware that they would have to have a job someday (thankfully they answered yes to that one). I remember on several occasions when I was an adolescent adult men trying to strike up conversations with me about matters on responsible adulthood as if they suspected my father of being deficient in these areas (perhaps he was, but as he seemed to me, and still does, much more intelligent and vital than most of these other people, their efforts did not leave much of an impression on me). Some of the upright blue collar types (policemen, independent contractors, etc) who populated our neighborhood (and who really disliked my father) took it upon themselves to talk to me about the necessity of morality and work ethic and proper decency in social intercourse, which I naturally resented, enough that this in part prompted me to move to Maine (where my father actually was). When I was there I remember the father of one of my friends, who was a lawyer, and didn't know my father, but had seen enough of me to not like the impression, giving me a harangue one evening at their dinner table about how I needed to be productive in my life, and how I was not productive. Anyway I wonder if something like that is going on now with my children. Still, I think because of my wife that the bar of acceptability may be already, and for the most part unconsciously on her part, set higher than I suspect it is. I believe that certain failures of will or talent or fortune that cannot be overcome are possibilities that I do not think she believes are possibilities, because they are not an imbued part of her experience. I certainly hope that this is the dominant impression that the children will receive in these instances.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1997)

This is the Disney cartoon version. I want to record and leave at least a brief note on all of the highly rated movies I see. Going on twelve years of having small children, a cartoon has to have something really, really unique and appealing about it for me to take much of an interest in it. That was not the case here, though I acknowledge the greatness of the story, the elements of which were ready-made to be classic, and were only waiting to be combined into a narrative. I don't know if the execution ever lives up to the promise offered by the scenario, as I have neither read the book nor seen any of the other numerous movie versions, several of which are considered classics in their own right. All of these I am pretty sure will turn up on one or another of my various lists at some point (if I live long enough, henceforth shortened to the internet word IILLE).

Sometimes I do searches on this blog to see if I have ever, in seven and a half years, used certain words. Today I discovered that I have never used the word "spreading" in this blog (Until now).

When I was really little I thought The Hunchback of Notre Dame was a true story about football.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment