The Pilgrimage to Parnassus; The Return from Parnassus (c. 1598-1602)

A series of plays put on at St John's College, Cambridge around the end of the Elizabethan period, as part of their Christmas festivities, though they are not about Christmas. They are about a couple of students who decide to make their way in the world as poets, and the predictable indifference, humiliation, and poverty that befall them when they set out to do this. There is some comfort in being reminded that the problem of impractical young people with liberal arts degrees leaving school without any prospects for obtaining an income, nor any realization of how one might ever go about developing any did not just spring up in the last 20 years. Maybe these kinds of schools, which ironically seem to be most emotionally necessary as a pleasant refuge during youth from the otherwise pitiless business of real life for the less successful of their graduates, will continue to sputter along in some form, in spite of even the most well-meaning, though mistaken efforts to kill them off and spare these more hopeless graduates from what is perceived to be the source of all of their perceived subsequent misery.

The plays themselves are hard going at times to read--I guess they have not been edited so as to be made intelligible to modern readers, assuming that can be done, and there are lots of references to people and inside jokes and slang that doubtless meant something to the assembled audience but can signify nothing to me. There are numerous references to contemporary as well as historical English poets (i.e. Chaucer), including Shakespeare, which accounts in some part for its historical interest. Shakespeare is identified only as a poet and the author of the Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis. His plays I did not notice as being referenced at all, though even by 1598 a good part of the comedies and histories would already have been written.

It could be interesting if it could be made more intelligible, I guess, though even most of the experts seem to be of the opinion that only the middle play (the first part of The Return) contains any real literary value.

Philippics--Cicero (44-43 B.C.)

This was the first Cicero I had ever read, and I am well into my forties. My education has been light on the Romans, so he is not the last of them that I have yet to read either (all in translation, of course, which I know scarcely counts anyway). These writings, being purportedly the transcripts of orations, are much different in tone from those of other classical authors with which I am familiar, having much more raw agitation and hostility in them. Of course Cicero here is an active partisan politician who has to sway the wavering opinions of, if not precisely a mob, a body of senators. I suppose I was expecting the style of delivery and the subject matter to be grander, less earthbound.

The Young Cicero Reading--Vicenzo Foppa (1464)

The fourteen Philippics are denunciations of Mark Antony, who at this time following the assassination of Julius Caesar was out of the city seeking military allies and in Cicero's opinion carrying on the worst of the dead Caesar's transgressions against the traditions of the old Republic. It is a different view of Antony than we usually get from both classical and post-renaissance literature. His arrogance, which in other depictions is usually presented with a heavy emphasis on vanity, here is expressed as of a more dangerous and willful quality. He is ambitious, a driver of events and a leader, of sorts anyway. I didn't previously think of him (based mainly on Plutarch and all the Shakespeare and Cleopatra plays) as a man capable of rousing this degree of anger and condemnation as a main target in himself, separate from his association with other people or events that are greater than he is.

I did not read this all that well. I suppose it is possible that the entire book is not great as a whole (various of the individual Philippics, especially the second, seem to be considered more important than the whole collection), maybe the translation did not perfectly capture the mood of high excitement and historical seriousness. I also have the sense that the Orations against Catiline (which Cicero himself, reliving that glory, references dozens of times in the course of the Philippics) are the essential Ciceronian reading. In any case he demands a more serious consideration than I seem to be able to give him at present.

Ben Jonson's Conversations with Drummond of Hawthornden (1618-19)

There is not much conversation here, on Drummond's part anyway, and what was recorded was mostly snippets--what would become popularly known as table talk--of Ben Jonson's observations, which amounted to 58 printed pages, most of which were more than half taken up with footnotes. The impression given is that there was not much in the way of give and take between Drummond and his guest, but that their talk consisted mostly of Jonson making pronouncements in a vaguely bullying manner. I don't remember much of this, either. Obviously I have reached the point where it is pointless for me to read any more. I am struck by so little of it, and as you can see I have trouble even putting my most simple general observations into words at this point. But I would have to take up some other pursuit to fill the time--I still can't just spend all my waking hours doing laundry and dishes, but maybe I am being ground down to the state where that is all I will be capable of doing--and I still desperately want to have some communication with the reasonably intelligent (and socially relevant) part of the world, and I don't know how else I can achieve this than by some attempt at producing content.

Drummond of Hawthornden

Tour of the Hebrides--Boswell (1773)

Not included in most editions of the Life of Johnson, this comparatively under-celebrated work is a book-sized bonus treat for people like me who are fans of this lively duo and their exploits in the social and literary society of their day. Johnson wrote his own account of this famous trip as well, which is one last further treat for me to look forward to, assuming I ever get around to reading it.

This is the edition I read.

I ordered my copy of this book online, and as sometimes happens with older memoir-type books, the edition I received was not the edited and polished standard one that all of the professors and other critics who have promoted the book as great are primarily thinking of, but the rougher version of the tour as it appeared in Boswell's journals. Nothing was left out as far as the major episodes of the trip went; on several occasions where pages of the journal had gone missing, the editors filled in the missing parts with the text from the printed Tour. These finished excerpts were far superior from a reading standpoint to the journal account, giving off much of the same high-spiritedness and humor of the Life itself, and I kind of wish now I had abandoned my edition entirely and found a copy of the traditional printed Tour. The journal was by no means a bad read, and almost certainly was more representative of what the trip was like on a day to day basis. There were numerous passages in it detailing parts of the trip where Johnson especially was bored and restless on account of the inferior level of education and dull conversation of many of the people they encountered, which provoked in him some rather harsh and decidedly unforgiving observations with regard to the limitations that several of their hosts and new acquaintances had revealed. My impression from the scholarly notes is that most of this material was either left out of the published version, or softened so as to appear more in a humorous and flattering light. And I think this was a good idea, as much of the special quality of these Johnson books come from the atmosphere of heightened intellectual alertness and drama that the scenes in them evoke. The life and conversation in them is far more entertaining and captivating than anything that ever occurs in real time, while plausibly resembling reality (if nothing else, the contrast between the journal and the published book reminds the reader of the art that is essential even in the production of a ostensibly non-fiction account to give it this sheen of heightened reality); but I realize more and more that it is these appearances of life heightened and made more consistently intense and significant and exhilirating that I seek in reading and other artistic entertainment.

Showing posts with label roman empire. Show all posts

Showing posts with label roman empire. Show all posts

Wednesday, January 07, 2015

Wednesday, February 03, 2010

I Have a New Scanner I Need to Try Out

This one is a piece of cake to use, which means, I am afraid, you can expect to see ever more of my detritus as time goes on. I believe a few months ago when I was recording my reading of something by Shelley that I threatened some Rome vacation pictures as accompaniment, only to discover that my old scanner was broken. So I give them to you now. I have tried to keep in mind that everybody already is familiar with the major monuments and sights in that city and tried to keep the photos to relative novelties.

This particular trip was in February/March 2001. Before I had children instead of going to Florida every year for winter vacation I used to go to places like Italy, and clinging to the idea that I might someday be able to do so again, remote and perhaps even trivial as it seems, does offer a strange kind of psychological satisfaction during the grinding weeks and months and years of daily life. Doing the sights and sitting around sipping cheap red wine in a cafe in Rome is the kind of thing a lot of the smarter and more conscientious modern kids are moving on from, preferring to seek out nobler and more mutually enriching experiences like laboring on farms and learning how to make artisanal cheeses in Armenia, or digging wells and building schools in Africa. I still found it pretty exciting to be there though. I guess arriving at the station or amidst one of the signature scenes of one of the great European capitals gets old for some people, though I have not been enough places for it to have happened with me yet.

On the Spanish Steps. I know this is a famous sight, but some people would be disappointed if I didn't include any pictures of pretty girls if I had them. I know I am when others don't. As for myself, I was looking rather bloated and had a bad haircut and an especially inane expression on my face on this trip, so there won't be much of me on view either. Pyramid of Gaius Cestius, a wealthy tribune of the early Empire, died 12 B.C. Now just outside the walls of the Protestant Cemetery.

Pyramid of Gaius Cestius, a wealthy tribune of the early Empire, died 12 B.C. Now just outside the walls of the Protestant Cemetery.

Grave of Devereux Platagenet Cockburn. Wealthy Victorian-era Romantic/foppish type who died in Rome at the age of 21. I thought his tomb was interesting. He isn't otherwise anybody notable.

Grave of Devereux Platagenet Cockburn. Wealthy Victorian-era Romantic/foppish type who died in Rome at the age of 21. I thought his tomb was interesting. He isn't otherwise anybody notable.

Unlike this Guy. There we are, the grave of Shelley, who actually drowned off the coast of, I don't remember where, Lerici and Leghorn (Livorno) are standing out (It was Leghorn). Some part of his body, probably his heart, was returned to England and interred at Bournemouth with his wife and her famous parents. He is not alone however, as his good friend and I believe biographer Edward Trelawny, who lived until 1881, dying at the age of 88 (grave not shown) is buried alongside him.

Unlike this Guy. There we are, the grave of Shelley, who actually drowned off the coast of, I don't remember where, Lerici and Leghorn (Livorno) are standing out (It was Leghorn). Some part of his body, probably his heart, was returned to England and interred at Bournemouth with his wife and her famous parents. He is not alone however, as his good friend and I believe biographer Edward Trelawny, who lived until 1881, dying at the age of 88 (grave not shown) is buried alongside him.

I Pose at Shelley's Grave. I am not sure what the purpose of doing this is, I admit. It is less of an oddity with the Romantic poets since it is the sort of thing they did themselves all the time. I'm sure I've seen an etching somewhere of Shelley or Byron at the tomb of Dante in Ravenna in the posture of trying to channel the master's spirit. With more modern writers, and the growth of the active, or wannabe active, segment of the literary world beyond reasonably intimate limits, these kinds of attempts at commiseration are a little more problematic. I saw that of course J.D. Salinger is not going to be buried, and doubtless whatever is done with his remains is not going to be revealed to the public. Einstein I believe took a similar approach, in large part in distaste at the idea of his tomb or whatever becoming a kind of shrine. On the other hand, when Norman Mailer died he was interred with some fanfare at Provincetown in Massachusetts; one suspects that the prospect of his monument's attracting attention after he had passed did not displease him.

I Pose at Shelley's Grave. I am not sure what the purpose of doing this is, I admit. It is less of an oddity with the Romantic poets since it is the sort of thing they did themselves all the time. I'm sure I've seen an etching somewhere of Shelley or Byron at the tomb of Dante in Ravenna in the posture of trying to channel the master's spirit. With more modern writers, and the growth of the active, or wannabe active, segment of the literary world beyond reasonably intimate limits, these kinds of attempts at commiseration are a little more problematic. I saw that of course J.D. Salinger is not going to be buried, and doubtless whatever is done with his remains is not going to be revealed to the public. Einstein I believe took a similar approach, in large part in distaste at the idea of his tomb or whatever becoming a kind of shrine. On the other hand, when Norman Mailer died he was interred with some fanfare at Provincetown in Massachusetts; one suspects that the prospect of his monument's attracting attention after he had passed did not displease him.

Oppian Hill; Scant Remains of the Bath of Titus (with Colosseum in Background). Before the baths of Titus this was also the site of the villa of Maecenas, the great patron of Horace and other poets and artists whose name indeed became synonomous with patronage down even to our own time.

Oppian Hill; Scant Remains of the Bath of Titus (with Colosseum in Background). Before the baths of Titus this was also the site of the villa of Maecenas, the great patron of Horace and other poets and artists whose name indeed became synonomous with patronage down even to our own time.

This one is a piece of cake to use, which means, I am afraid, you can expect to see ever more of my detritus as time goes on. I believe a few months ago when I was recording my reading of something by Shelley that I threatened some Rome vacation pictures as accompaniment, only to discover that my old scanner was broken. So I give them to you now. I have tried to keep in mind that everybody already is familiar with the major monuments and sights in that city and tried to keep the photos to relative novelties.

This particular trip was in February/March 2001. Before I had children instead of going to Florida every year for winter vacation I used to go to places like Italy, and clinging to the idea that I might someday be able to do so again, remote and perhaps even trivial as it seems, does offer a strange kind of psychological satisfaction during the grinding weeks and months and years of daily life. Doing the sights and sitting around sipping cheap red wine in a cafe in Rome is the kind of thing a lot of the smarter and more conscientious modern kids are moving on from, preferring to seek out nobler and more mutually enriching experiences like laboring on farms and learning how to make artisanal cheeses in Armenia, or digging wells and building schools in Africa. I still found it pretty exciting to be there though. I guess arriving at the station or amidst one of the signature scenes of one of the great European capitals gets old for some people, though I have not been enough places for it to have happened with me yet.

On the Spanish Steps. I know this is a famous sight, but some people would be disappointed if I didn't include any pictures of pretty girls if I had them. I know I am when others don't. As for myself, I was looking rather bloated and had a bad haircut and an especially inane expression on my face on this trip, so there won't be much of me on view either.

Pyramid of Gaius Cestius, a wealthy tribune of the early Empire, died 12 B.C. Now just outside the walls of the Protestant Cemetery.

Pyramid of Gaius Cestius, a wealthy tribune of the early Empire, died 12 B.C. Now just outside the walls of the Protestant Cemetery. Grave of Devereux Platagenet Cockburn. Wealthy Victorian-era Romantic/foppish type who died in Rome at the age of 21. I thought his tomb was interesting. He isn't otherwise anybody notable.

Grave of Devereux Platagenet Cockburn. Wealthy Victorian-era Romantic/foppish type who died in Rome at the age of 21. I thought his tomb was interesting. He isn't otherwise anybody notable. Unlike this Guy. There we are, the grave of Shelley, who actually drowned off the coast of, I don't remember where, Lerici and Leghorn (Livorno) are standing out (It was Leghorn). Some part of his body, probably his heart, was returned to England and interred at Bournemouth with his wife and her famous parents. He is not alone however, as his good friend and I believe biographer Edward Trelawny, who lived until 1881, dying at the age of 88 (grave not shown) is buried alongside him.

Unlike this Guy. There we are, the grave of Shelley, who actually drowned off the coast of, I don't remember where, Lerici and Leghorn (Livorno) are standing out (It was Leghorn). Some part of his body, probably his heart, was returned to England and interred at Bournemouth with his wife and her famous parents. He is not alone however, as his good friend and I believe biographer Edward Trelawny, who lived until 1881, dying at the age of 88 (grave not shown) is buried alongside him. I Pose at Shelley's Grave. I am not sure what the purpose of doing this is, I admit. It is less of an oddity with the Romantic poets since it is the sort of thing they did themselves all the time. I'm sure I've seen an etching somewhere of Shelley or Byron at the tomb of Dante in Ravenna in the posture of trying to channel the master's spirit. With more modern writers, and the growth of the active, or wannabe active, segment of the literary world beyond reasonably intimate limits, these kinds of attempts at commiseration are a little more problematic. I saw that of course J.D. Salinger is not going to be buried, and doubtless whatever is done with his remains is not going to be revealed to the public. Einstein I believe took a similar approach, in large part in distaste at the idea of his tomb or whatever becoming a kind of shrine. On the other hand, when Norman Mailer died he was interred with some fanfare at Provincetown in Massachusetts; one suspects that the prospect of his monument's attracting attention after he had passed did not displease him.

I Pose at Shelley's Grave. I am not sure what the purpose of doing this is, I admit. It is less of an oddity with the Romantic poets since it is the sort of thing they did themselves all the time. I'm sure I've seen an etching somewhere of Shelley or Byron at the tomb of Dante in Ravenna in the posture of trying to channel the master's spirit. With more modern writers, and the growth of the active, or wannabe active, segment of the literary world beyond reasonably intimate limits, these kinds of attempts at commiseration are a little more problematic. I saw that of course J.D. Salinger is not going to be buried, and doubtless whatever is done with his remains is not going to be revealed to the public. Einstein I believe took a similar approach, in large part in distaste at the idea of his tomb or whatever becoming a kind of shrine. On the other hand, when Norman Mailer died he was interred with some fanfare at Provincetown in Massachusetts; one suspects that the prospect of his monument's attracting attention after he had passed did not displease him. Oppian Hill; Scant Remains of the Bath of Titus (with Colosseum in Background). Before the baths of Titus this was also the site of the villa of Maecenas, the great patron of Horace and other poets and artists whose name indeed became synonomous with patronage down even to our own time.

Oppian Hill; Scant Remains of the Bath of Titus (with Colosseum in Background). Before the baths of Titus this was also the site of the villa of Maecenas, the great patron of Horace and other poets and artists whose name indeed became synonomous with patronage down even to our own time.I know a lot of people aren't big on ruins, but if you have some sense of or feeling for the world of antiquity--even a Victorian one--they can be very inspiring, especially if the surrounding landscape has retained a plausibly ancient appearance.

One of the Pools at the Villa. It wasn't crowded when we were there, so the place was nearly silent, it is you practically all alone on the vast estate of one of the greatest Roman Emperors, the remains of pools, theaters, baths, a Greek library and a Latin library, beautiful scenery, no cynical or jabbering or critical voices dampening your absorption. It is really a quite heady experience.

One of the Pools at the Villa. It wasn't crowded when we were there, so the place was nearly silent, it is you practically all alone on the vast estate of one of the greatest Roman Emperors, the remains of pools, theaters, baths, a Greek library and a Latin library, beautiful scenery, no cynical or jabbering or critical voices dampening your absorption. It is really a quite heady experience.

But now look at all the things I did not see when I was there. The famous statue of Moses by Michelangelo in the church of St Peter-in-Chains; various of the other celebrated churches (981 in all) such as St John Laterano and St Paul outside-the-walls. The Borghese Gallery. The grounds of the Forum itself. I should still like to see those things. Perhaps I should do something for the world first, and earn the privilege. That seems to be the attitude the most proper people from my social class anyway take nowadays.

But now look at all the things I did not see when I was there. The famous statue of Moses by Michelangelo in the church of St Peter-in-Chains; various of the other celebrated churches (981 in all) such as St John Laterano and St Paul outside-the-walls. The Borghese Gallery. The grounds of the Forum itself. I should still like to see those things. Perhaps I should do something for the world first, and earn the privilege. That seems to be the attitude the most proper people from my social class anyway take nowadays.

One of the Pools at the Villa. It wasn't crowded when we were there, so the place was nearly silent, it is you practically all alone on the vast estate of one of the greatest Roman Emperors, the remains of pools, theaters, baths, a Greek library and a Latin library, beautiful scenery, no cynical or jabbering or critical voices dampening your absorption. It is really a quite heady experience.

One of the Pools at the Villa. It wasn't crowded when we were there, so the place was nearly silent, it is you practically all alone on the vast estate of one of the greatest Roman Emperors, the remains of pools, theaters, baths, a Greek library and a Latin library, beautiful scenery, no cynical or jabbering or critical voices dampening your absorption. It is really a quite heady experience. But now look at all the things I did not see when I was there. The famous statue of Moses by Michelangelo in the church of St Peter-in-Chains; various of the other celebrated churches (981 in all) such as St John Laterano and St Paul outside-the-walls. The Borghese Gallery. The grounds of the Forum itself. I should still like to see those things. Perhaps I should do something for the world first, and earn the privilege. That seems to be the attitude the most proper people from my social class anyway take nowadays.

But now look at all the things I did not see when I was there. The famous statue of Moses by Michelangelo in the church of St Peter-in-Chains; various of the other celebrated churches (981 in all) such as St John Laterano and St Paul outside-the-walls. The Borghese Gallery. The grounds of the Forum itself. I should still like to see those things. Perhaps I should do something for the world first, and earn the privilege. That seems to be the attitude the most proper people from my social class anyway take nowadays. Friday, June 05, 2009

Caesar & Cleopatra--Part 2

I am doing a second book report post in a row because I didn't feel like writing about anything else when I started this post last Thursday. I realize that I haven't undertaken any kind of longer essay-type piece in a while as I have become more accustomed to *blogging*. This is not improving my overall ability to either write or think however.

We are in Act III now.

APOLLODOROUS: "...when a stupid man is doing something he is ashamed of, he always declares that it is his duty."

One of the highest praises that can be bestowed on a work of art or thought is to declare that it tears one's previous assumptions to pieces. This "one" I assume is never quite everybody, except in works of the absolute highest genius, like the Principia or something; in most instances I assume (one of my assumptions here) that the author or artist's truth is not wholly but just generally unknown, and that the fellow whose mental superstructure is being torn apart is a common fellow who fancied himself to be more clever and knowledgeable about the world than reality justified and needed to be knocked down a peg or two. For otherwise the critics and the intellectuals would be having their assumptions devastated so frequently that I would think they would have to lose all faith in them and cease to be effective in their professions. This is sort of what has happened with me. Whatever my assumptions are, I know far better than to imagine they will stand up to any rigorous scrutiny when challenged, and I cannot seem to formulate for myself very many that will. If anything, my intellect is at this point so shredded that I find I cannot even deal with actual ideas at all most of the time but am just looking at things like basic sentence structures, word usages, running themes across particular strains of history, and the like, simply to try to recover some base of language and cultural possession to enable me to live out the remainder of my days in some semblance of a human condition formed under some influence of noble and civilizing forces.

I had forgotten about the stage direction where a hook-nosed man looks longingly at a purse. It is certainly crude, as well as petty, neither of which however is uncharacteristic of this author in his descriptions of characters he holds in low regard. Shaw seems to have been pretty blatantly anti-Semitic, certainly by any standard that would be acceptable today. The main argument usually presented in his semi-defense is that he was more or less a general misanthrope, but this latter affliction, which literature at least often finds to be secretly lovable, is distinct from racial bigotry, which is certainly held to be a much worse wrong, either as based on faultier premises, supposing guilt, or suspicion, but peculiar to and by association with the particular group being demonized, and of which, of course, the bigot can with greater assurance claim and feel no association. I knew of nothing of this some years ago when I was visiting the home of a (Jewish) friend of mine, and blithely responded when the father, an old New Yorker, asked me what I was reading lately, Arms and the Man. "Really," the man had said, not in an angry but more an incredulous tone, "I didn't think anybody read Shaw anymore." Nothing at the time so much as set off the slightest suspicion in my mind that Shaw might be offensive to this guy. I just thought he was laughing at it (which maybe he was that, too). The tone however was just weird enough that it always kind of stuck with me. I was not really sure at this point where Act III was going, and felt compelled to record this in my notes. Caesar makes more idiosyncratic political statements (to the suggestion that he examine some letters which will reveal who is plotting against him, he replies "Would you have me waste the next three years of my life in proscribing and condemning men who will be my friends when I have proved that my friendship is worth more than Pompey's was--than Cato's is") and the act ends with a demonstration of the excitement alpha males like himself arouse in everyone around them when he makes a minor military attack that appears dangerous to the others in his party (and in which he easily triumphs) an occasion for spontaneous gaiety and even hijinks.

I was not really sure at this point where Act III was going, and felt compelled to record this in my notes. Caesar makes more idiosyncratic political statements (to the suggestion that he examine some letters which will reveal who is plotting against him, he replies "Would you have me waste the next three years of my life in proscribing and condemning men who will be my friends when I have proved that my friendship is worth more than Pompey's was--than Cato's is") and the act ends with a demonstration of the excitement alpha males like himself arouse in everyone around them when he makes a minor military attack that appears dangerous to the others in his party (and in which he easily triumphs) an occasion for spontaneous gaiety and even hijinks.

Act IV begins with a satire of a pompous musician which is moderately funny if you are in the right mood.

(Later) CAESAR: "...Oh, this military life! this tedious, brutal life of action! That is the worst of us Romans: we are mere doers and drudgers: a swarm of bees turned into men. Give me a good talker--one with wit and imagination enough to live without continually doing something." This will have to speak for itself.

I know nothing about food, so most of the jokes in the section about Caesar's dinner I don't quite get. He raves at some length about the greatness of British oysters, which I assumed was facetious, but my researches indicate that the general opinion of them is that they are good. He then requests barley water instead of wine and threatens to outlaw extravagances of diet when he gets back to Rome. Austerity of diet is one of Shaw's pet themes. Among other things, I know he was a vegetarian, and his funeral featured, at his own direction, a parade of various animals he had pointedly not eaten in life.

I know nothing about food, so most of the jokes in the section about Caesar's dinner I don't quite get. He raves at some length about the greatness of British oysters, which I assumed was facetious, but my researches indicate that the general opinion of them is that they are good. He then requests barley water instead of wine and threatens to outlaw extravagances of diet when he gets back to Rome. Austerity of diet is one of Shaw's pet themes. Among other things, I know he was a vegetarian, and his funeral featured, at his own direction, a parade of various animals he had pointedly not eaten in life.

I am doing a second book report post in a row because I didn't feel like writing about anything else when I started this post last Thursday. I realize that I haven't undertaken any kind of longer essay-type piece in a while as I have become more accustomed to *blogging*. This is not improving my overall ability to either write or think however.

We are in Act III now.

APOLLODOROUS: "...when a stupid man is doing something he is ashamed of, he always declares that it is his duty."

One of the highest praises that can be bestowed on a work of art or thought is to declare that it tears one's previous assumptions to pieces. This "one" I assume is never quite everybody, except in works of the absolute highest genius, like the Principia or something; in most instances I assume (one of my assumptions here) that the author or artist's truth is not wholly but just generally unknown, and that the fellow whose mental superstructure is being torn apart is a common fellow who fancied himself to be more clever and knowledgeable about the world than reality justified and needed to be knocked down a peg or two. For otherwise the critics and the intellectuals would be having their assumptions devastated so frequently that I would think they would have to lose all faith in them and cease to be effective in their professions. This is sort of what has happened with me. Whatever my assumptions are, I know far better than to imagine they will stand up to any rigorous scrutiny when challenged, and I cannot seem to formulate for myself very many that will. If anything, my intellect is at this point so shredded that I find I cannot even deal with actual ideas at all most of the time but am just looking at things like basic sentence structures, word usages, running themes across particular strains of history, and the like, simply to try to recover some base of language and cultural possession to enable me to live out the remainder of my days in some semblance of a human condition formed under some influence of noble and civilizing forces.

I had forgotten about the stage direction where a hook-nosed man looks longingly at a purse. It is certainly crude, as well as petty, neither of which however is uncharacteristic of this author in his descriptions of characters he holds in low regard. Shaw seems to have been pretty blatantly anti-Semitic, certainly by any standard that would be acceptable today. The main argument usually presented in his semi-defense is that he was more or less a general misanthrope, but this latter affliction, which literature at least often finds to be secretly lovable, is distinct from racial bigotry, which is certainly held to be a much worse wrong, either as based on faultier premises, supposing guilt, or suspicion, but peculiar to and by association with the particular group being demonized, and of which, of course, the bigot can with greater assurance claim and feel no association. I knew of nothing of this some years ago when I was visiting the home of a (Jewish) friend of mine, and blithely responded when the father, an old New Yorker, asked me what I was reading lately, Arms and the Man. "Really," the man had said, not in an angry but more an incredulous tone, "I didn't think anybody read Shaw anymore." Nothing at the time so much as set off the slightest suspicion in my mind that Shaw might be offensive to this guy. I just thought he was laughing at it (which maybe he was that, too). The tone however was just weird enough that it always kind of stuck with me.

I was not really sure at this point where Act III was going, and felt compelled to record this in my notes. Caesar makes more idiosyncratic political statements (to the suggestion that he examine some letters which will reveal who is plotting against him, he replies "Would you have me waste the next three years of my life in proscribing and condemning men who will be my friends when I have proved that my friendship is worth more than Pompey's was--than Cato's is") and the act ends with a demonstration of the excitement alpha males like himself arouse in everyone around them when he makes a minor military attack that appears dangerous to the others in his party (and in which he easily triumphs) an occasion for spontaneous gaiety and even hijinks.

I was not really sure at this point where Act III was going, and felt compelled to record this in my notes. Caesar makes more idiosyncratic political statements (to the suggestion that he examine some letters which will reveal who is plotting against him, he replies "Would you have me waste the next three years of my life in proscribing and condemning men who will be my friends when I have proved that my friendship is worth more than Pompey's was--than Cato's is") and the act ends with a demonstration of the excitement alpha males like himself arouse in everyone around them when he makes a minor military attack that appears dangerous to the others in his party (and in which he easily triumphs) an occasion for spontaneous gaiety and even hijinks.Act IV begins with a satire of a pompous musician which is moderately funny if you are in the right mood.

(Later) CAESAR: "...Oh, this military life! this tedious, brutal life of action! That is the worst of us Romans: we are mere doers and drudgers: a swarm of bees turned into men. Give me a good talker--one with wit and imagination enough to live without continually doing something." This will have to speak for itself.

I know nothing about food, so most of the jokes in the section about Caesar's dinner I don't quite get. He raves at some length about the greatness of British oysters, which I assumed was facetious, but my researches indicate that the general opinion of them is that they are good. He then requests barley water instead of wine and threatens to outlaw extravagances of diet when he gets back to Rome. Austerity of diet is one of Shaw's pet themes. Among other things, I know he was a vegetarian, and his funeral featured, at his own direction, a parade of various animals he had pointedly not eaten in life.

I know nothing about food, so most of the jokes in the section about Caesar's dinner I don't quite get. He raves at some length about the greatness of British oysters, which I assumed was facetious, but my researches indicate that the general opinion of them is that they are good. He then requests barley water instead of wine and threatens to outlaw extravagances of diet when he gets back to Rome. Austerity of diet is one of Shaw's pet themes. Among other things, I know he was a vegetarian, and his funeral featured, at his own direction, a parade of various animals he had pointedly not eaten in life. Why have Caesar denounce vengeance and violence? Because unlike lesser men he knows what he is talking about? Because he is great and different standards are applied to his character? Because human excellence presupposes, due to the overall baseness of the race, a certain necessity of unsavory action to move humanity forward? Because in Shaw's moral system, understanding and being able to explain your reasons for what you are doing is the most important quality, and is the only possible source of human good attainable?

RUFIO: "Tell your executioner that if Pothinus had been properly killed--i n t h e t h r o a t--he would not have called out. Your man bungled his work." I thought it might be useful to remember this someday.

BELZANOR: A marvelous man, this Caesar! Will he come soon, think you?

APPOLLODORUS: He was settling the Jewish question when I left.

Another pretty rough joke, if you look at it either from the point of view that the "Jewish question" the implication of which I take here to be "how to either render the Jews more or less docile and impotent in society (A) under question or find somewhere else (B) where they can go which will make everyone happy", could be considered never to have been settled to the satisfaction, or at least resignation, of all interests, or also that Caesar's way of "settling" questions, while breezily alluded to in the dialogue here, could suggest rather brutal connotations.

APPOLLODORUS: ...Rome will produce no art itself; but it will buy up and take away whatever the other nations produce.

CAESAR: What! Rome produce no art! Is peace not an art? is war not an art? is government not an art? is civilization not an art? All these we give you in exchange for a few ornaments. You will have the best of the bargain...

The interesting quality of these plays is that they are never earnest with regard to their ideas in themselves apart from the character who is speaking them. It is in the person and mind of the particular character only that ideas have value and merit consideration. Ideas are only important really in the sense of how they take hold in and act upon stupid people, which is where they become dangerous. A world where everyone was of fairly equal (high) intelligence and more or less had a good grasp of what was going on would, it is suggested, mitigate the effects any particular distortion of a human phenomenon could have.

I'll have to do one more on this.

I'll have to do one more on this.

Monday, June 01, 2009

George Bernard Shaw--Caesar and Cleopatra--Part 1 (1907)

I had a dream the other night that my wife had decided that our lives had grown stale and that we had consequently moved to Los Angeles (the chance of this happening in real life is zero). This Los Angeles was more like a wine-growing country or at least the back lot towns and villages in movies from Charlie Chaplin's era than anything like Los Angeles is supposed to be now. Being me, I naturally went straight to a TV studio to look for work (I apparently arrived in town unemployed), and all the employees talked in the exaggerated style of commercials and game show hosts. And I loved it. I was quite confident I was going to be offered a good position in the industry too--perhaps acting like a person on television?--based on these positive first impressions. I was thinking this was really a brilliant and invigorating midlife move, just what I needed. My wife seemed happy to be in California too. In reality of course I have never been to California. I would still like to go someday, but it strikes as a place you can't really go to on vacation and get much out of it, unless it's for six weeks at least. Probably you really have to live there for a time, and trying to achieve something that you haven't achieved before and can't achieve in the same way anywhere else. That is what people do there. You have to have some purpose.

George Bernard Shaw is a funny kind of writer to read today, about a hundred years after his heyday. It is easy to tear apart his political and social opinions, declare their fallacies and feel generally superior about oneself from the internet commentator understanding of the world, but from the literary point of view he was really quite brilliant. His plots and situations are truly funny and ingenious compared to almost all other writers. He was a great iconoclast, in a time when the whole of cultural life was dominated by icons and idols in which people had a lot invested, and it is this that I take to be the main object and value of his assertions. I think you have to be wary of taking much of what he says literally and seriously. I can pretty much be brought to believe in anything if it is presented well enough, but there are always several occasions in any Shaw play where I find myself writing "This guy is totally full of shit" or something to that effect. That, and all the doubts one has about this author's sincerity, decency, courage, that you either detect from the writing or see hinted at in the commentaries of other authors, aside, Caesar and Cleopatra is a highly entertaining--not to mention short--piece of literature. Take it to the beach even, if you go to a beach where it would not be wholly unreasonable to whip out a copy of G.B. Shaw. I think you could do this at East Hampton town beach in NY, Ipswich in MA, Rye and nearby state beaches in NH, York (Long Sands), Ogunquit and Kennebunk in ME, among doubtless many others. It's a very smart play, even if half the opinions or more expressed in it are dubious; indeed, it even causes one to question the importance of having correct opinions, or if these are actually possible given the absurd state of human existence.

My Model Hasn't Figured How to Pose the Cover of the Book For the Camera Yet. Which is why you see a struggle taking place for the positioning of the book. Act I begins with more irreverent stage directions than are customary. Examples: "Below...are two notable drawbacks of civilization: a palace, and soldiers." "The palace...is not so ugly as Buckingham Palace." "(Belzanor, a warrior) Is rather to be pitied just now in view of the fact that Julius Caesar is invading his country." It is thus established right way that one must be wary of taking anything seriously with George Bernard Shaw.

Act I begins with more irreverent stage directions than are customary. Examples: "Below...are two notable drawbacks of civilization: a palace, and soldiers." "The palace...is not so ugly as Buckingham Palace." "(Belzanor, a warrior) Is rather to be pitied just now in view of the fact that Julius Caesar is invading his country." It is thus established right way that one must be wary of taking anything seriously with George Bernard Shaw.

A soldier entering the camp in flight from a battle with the Romans ("I am Bel Affris, descended from the gods." (Auditors) "Hail, cousin!" states that their javelins "drove through my shield as through a papyrus." I thought that was funny.

The Romans seem, after some degree of consideration, to be an exteme case of a race of men that is more exciting to read about than to experience first hand.

There is an absurd exchange among the besieged Egyptians regarding whether they should kill the women to protect them from the Romans. At length it is decided that it would be cheaper to let the Romans kill them, because they would have to pay blood money if they did it themselves.

This Was a Picture of the Box of a Caesar and Cleopatra Card Game. I am surprised they do not allow it to be shown, as it would be good advertising for them. Who is more likely to buy this kind of game than the kind of person who would find this site distracting?

The stage directions for Act II, ostensibly laying out for us the scene at Cleopatra's palace, include one of George Bernard Shaw's most cherished hobby horses, a direct dig at the English bourgeoisie ("The clean lofty walls...absence of mirrors, sham perspectives, stuffy upholsteries and textiles, make the place handsome, wholesome, simple and cool, or, as a rich English manufacturer would express it, poor, bare, ridiculous and unhomely"). Bourgeois sensibilities never change of course, because such people, I gather from my reading, have no other distinguishing personal characteristics than what can be glossed from their possessions and their manner of ornament, so the observation can more or less be applied to the same crew in our own time and nation.

The stage directions for Act II, ostensibly laying out for us the scene at Cleopatra's palace, include one of George Bernard Shaw's most cherished hobby horses, a direct dig at the English bourgeoisie ("The clean lofty walls...absence of mirrors, sham perspectives, stuffy upholsteries and textiles, make the place handsome, wholesome, simple and cool, or, as a rich English manufacturer would express it, poor, bare, ridiculous and unhomely"). Bourgeois sensibilities never change of course, because such people, I gather from my reading, have no other distinguishing personal characteristics than what can be glossed from their possessions and their manner of ornament, so the observation can more or less be applied to the same crew in our own time and nation.

The part where Caesar's aide-de-camp Rufio "with Roman resourcefulness and indifference to foreign superstitions" dismantles the tripod where incense was burning upon entering the palace because it was in Caesar's way I thought was presented amusingly.

Cleopatra is 16 in this play, and Shaw writes her as a silly and totally naive (though intelligent) schoolgirl ("Mark Antony, Mark Antony, Mark Antony! What a beautiful name!"). I don't know how accurate this take is--my impression is that 16-year old girls from educated backgrounds in the Victorian and Edwardian eras were more sheltered from the sordidities of worldly social life than has been common historically--but it does add a degree of charm to the play.

At one point in Act II the famous library of Alexandria catches on fire (though something like this does seem to have happened during Caesar's invasion, the big and final destruction especially lamented by scholars, historians, book lovers, etc. occurred several centuries afterwards). Shaw presents the occasion as the notorious fire however, or at least implies it, and naturally uses the opportunity to skewer anyone who might be inclined to regard the event as some kind of tragedy:

CAESAR (on hearing from an hysterical scholarly type that the library is in flames): Is that all?

THEODOTUS (the hysterical scholar) (S.D. unable to believe his senses): All! Caesar: will you go down to posterity as a barbarous soldier too ignorant to know the value of books?

CAESAR: Theodotus: I am an author myself; and I tell you it is better that the Egyptians should live their lives than dream them away with the help of books.

THEODOTUS (kneeling, with genuine literary emotion: the passion of the pedant): Caesar: once in ten generations of men, the world gains an immortal book.

CAESAR (inflexible): If it did not flatter mankind, the common executioner would burn it.

THEODOTUS: Without history, death would lay you beside your meanest soldier.

CAESAR: Death will do that in any case. I ask no better grave.

While Shaw may have (sort of) believed all of these things about books, I find it highly improbable that Julius Caesar would have been in quite as close agreement with his sentiments on the matter as this play would suggest. Do I agree with any of it? I agree that books and other entertainments--and if you are of a pedantic nature, even a work of incomprehensible philosophy can still serve as an entertainment for you in the contemplation of reading/understanding it, etc--often have the unfortunate effect of substituting for any other engagement in life. It is not clear to me that removing the books will necessarily force an improvement in the typical faux-intellectual's level of engagement with life however.

Reading much Shaw at any one time can quickly become exasperating however, and leads one to ask the question, O.K., so what did Shaw like? I was able to come up with three possible things that he seems not at least to have openly detested. 1. I remember reading somewhere that he liked Wendy Hiller , who acted in a lot of his plays, and was the female lead in the outstanding movie versions of Major Barbara and Pygmalion. She was very good at playing the humor, which she clearly "got", and without which watching a production of Shaw would be excruciating. 2. Music? His mother was one of those fanatical Dublin singers and music aficiondos whose passion led so far as to bring trouble to her domestic life, and Shaw's early writing career consisted largely of music criticism, so it was at least central to his view of life. He probably would not have liked this though. 3. Caesar, evidently, at least in that he writes his character as being a great deal like George Bernard Shaw himself, which is a high compliment from the pen of this author.

Reading much Shaw at any one time can quickly become exasperating however, and leads one to ask the question, O.K., so what did Shaw like? I was able to come up with three possible things that he seems not at least to have openly detested. 1. I remember reading somewhere that he liked Wendy Hiller , who acted in a lot of his plays, and was the female lead in the outstanding movie versions of Major Barbara and Pygmalion. She was very good at playing the humor, which she clearly "got", and without which watching a production of Shaw would be excruciating. 2. Music? His mother was one of those fanatical Dublin singers and music aficiondos whose passion led so far as to bring trouble to her domestic life, and Shaw's early writing career consisted largely of music criticism, so it was at least central to his view of life. He probably would not have liked this though. 3. Caesar, evidently, at least in that he writes his character as being a great deal like George Bernard Shaw himself, which is a high compliment from the pen of this author.

Shaw loves to teach lessons and set people straight. Nowadays he would probably be the host of a talk radio program.

CLEOPATRA: "Those Roman helmets are so becoming." This is followed by a discussion of Caesar's baldness, which of course only someone with the mentality of a teenage girl would think important. Rules of playwriting for the entertainment of a bourgeois audience #1: Exploit any popular and easily recognized cliches your subject offers to the full (See Amadeus or any other popular biographical drama of a Great historical figure).

I had a dream the other night that my wife had decided that our lives had grown stale and that we had consequently moved to Los Angeles (the chance of this happening in real life is zero). This Los Angeles was more like a wine-growing country or at least the back lot towns and villages in movies from Charlie Chaplin's era than anything like Los Angeles is supposed to be now. Being me, I naturally went straight to a TV studio to look for work (I apparently arrived in town unemployed), and all the employees talked in the exaggerated style of commercials and game show hosts. And I loved it. I was quite confident I was going to be offered a good position in the industry too--perhaps acting like a person on television?--based on these positive first impressions. I was thinking this was really a brilliant and invigorating midlife move, just what I needed. My wife seemed happy to be in California too. In reality of course I have never been to California. I would still like to go someday, but it strikes as a place you can't really go to on vacation and get much out of it, unless it's for six weeks at least. Probably you really have to live there for a time, and trying to achieve something that you haven't achieved before and can't achieve in the same way anywhere else. That is what people do there. You have to have some purpose.

George Bernard Shaw is a funny kind of writer to read today, about a hundred years after his heyday. It is easy to tear apart his political and social opinions, declare their fallacies and feel generally superior about oneself from the internet commentator understanding of the world, but from the literary point of view he was really quite brilliant. His plots and situations are truly funny and ingenious compared to almost all other writers. He was a great iconoclast, in a time when the whole of cultural life was dominated by icons and idols in which people had a lot invested, and it is this that I take to be the main object and value of his assertions. I think you have to be wary of taking much of what he says literally and seriously. I can pretty much be brought to believe in anything if it is presented well enough, but there are always several occasions in any Shaw play where I find myself writing "This guy is totally full of shit" or something to that effect. That, and all the doubts one has about this author's sincerity, decency, courage, that you either detect from the writing or see hinted at in the commentaries of other authors, aside, Caesar and Cleopatra is a highly entertaining--not to mention short--piece of literature. Take it to the beach even, if you go to a beach where it would not be wholly unreasonable to whip out a copy of G.B. Shaw. I think you could do this at East Hampton town beach in NY, Ipswich in MA, Rye and nearby state beaches in NH, York (Long Sands), Ogunquit and Kennebunk in ME, among doubtless many others. It's a very smart play, even if half the opinions or more expressed in it are dubious; indeed, it even causes one to question the importance of having correct opinions, or if these are actually possible given the absurd state of human existence.

My Model Hasn't Figured How to Pose the Cover of the Book For the Camera Yet. Which is why you see a struggle taking place for the positioning of the book.

Act I begins with more irreverent stage directions than are customary. Examples: "Below...are two notable drawbacks of civilization: a palace, and soldiers." "The palace...is not so ugly as Buckingham Palace." "(Belzanor, a warrior) Is rather to be pitied just now in view of the fact that Julius Caesar is invading his country." It is thus established right way that one must be wary of taking anything seriously with George Bernard Shaw.

Act I begins with more irreverent stage directions than are customary. Examples: "Below...are two notable drawbacks of civilization: a palace, and soldiers." "The palace...is not so ugly as Buckingham Palace." "(Belzanor, a warrior) Is rather to be pitied just now in view of the fact that Julius Caesar is invading his country." It is thus established right way that one must be wary of taking anything seriously with George Bernard Shaw.A soldier entering the camp in flight from a battle with the Romans ("I am Bel Affris, descended from the gods." (Auditors) "Hail, cousin!" states that their javelins "drove through my shield as through a papyrus." I thought that was funny.

The Romans seem, after some degree of consideration, to be an exteme case of a race of men that is more exciting to read about than to experience first hand.

There is an absurd exchange among the besieged Egyptians regarding whether they should kill the women to protect them from the Romans. At length it is decided that it would be cheaper to let the Romans kill them, because they would have to pay blood money if they did it themselves.

This Was a Picture of the Box of a Caesar and Cleopatra Card Game. I am surprised they do not allow it to be shown, as it would be good advertising for them. Who is more likely to buy this kind of game than the kind of person who would find this site distracting?

The stage directions for Act II, ostensibly laying out for us the scene at Cleopatra's palace, include one of George Bernard Shaw's most cherished hobby horses, a direct dig at the English bourgeoisie ("The clean lofty walls...absence of mirrors, sham perspectives, stuffy upholsteries and textiles, make the place handsome, wholesome, simple and cool, or, as a rich English manufacturer would express it, poor, bare, ridiculous and unhomely"). Bourgeois sensibilities never change of course, because such people, I gather from my reading, have no other distinguishing personal characteristics than what can be glossed from their possessions and their manner of ornament, so the observation can more or less be applied to the same crew in our own time and nation.

The stage directions for Act II, ostensibly laying out for us the scene at Cleopatra's palace, include one of George Bernard Shaw's most cherished hobby horses, a direct dig at the English bourgeoisie ("The clean lofty walls...absence of mirrors, sham perspectives, stuffy upholsteries and textiles, make the place handsome, wholesome, simple and cool, or, as a rich English manufacturer would express it, poor, bare, ridiculous and unhomely"). Bourgeois sensibilities never change of course, because such people, I gather from my reading, have no other distinguishing personal characteristics than what can be glossed from their possessions and their manner of ornament, so the observation can more or less be applied to the same crew in our own time and nation.The part where Caesar's aide-de-camp Rufio "with Roman resourcefulness and indifference to foreign superstitions" dismantles the tripod where incense was burning upon entering the palace because it was in Caesar's way I thought was presented amusingly.

Cleopatra is 16 in this play, and Shaw writes her as a silly and totally naive (though intelligent) schoolgirl ("Mark Antony, Mark Antony, Mark Antony! What a beautiful name!"). I don't know how accurate this take is--my impression is that 16-year old girls from educated backgrounds in the Victorian and Edwardian eras were more sheltered from the sordidities of worldly social life than has been common historically--but it does add a degree of charm to the play.

At one point in Act II the famous library of Alexandria catches on fire (though something like this does seem to have happened during Caesar's invasion, the big and final destruction especially lamented by scholars, historians, book lovers, etc. occurred several centuries afterwards). Shaw presents the occasion as the notorious fire however, or at least implies it, and naturally uses the opportunity to skewer anyone who might be inclined to regard the event as some kind of tragedy:

CAESAR (on hearing from an hysterical scholarly type that the library is in flames): Is that all?

THEODOTUS (the hysterical scholar) (S.D. unable to believe his senses): All! Caesar: will you go down to posterity as a barbarous soldier too ignorant to know the value of books?

CAESAR: Theodotus: I am an author myself; and I tell you it is better that the Egyptians should live their lives than dream them away with the help of books.

THEODOTUS (kneeling, with genuine literary emotion: the passion of the pedant): Caesar: once in ten generations of men, the world gains an immortal book.

CAESAR (inflexible): If it did not flatter mankind, the common executioner would burn it.

THEODOTUS: Without history, death would lay you beside your meanest soldier.

CAESAR: Death will do that in any case. I ask no better grave.

While Shaw may have (sort of) believed all of these things about books, I find it highly improbable that Julius Caesar would have been in quite as close agreement with his sentiments on the matter as this play would suggest. Do I agree with any of it? I agree that books and other entertainments--and if you are of a pedantic nature, even a work of incomprehensible philosophy can still serve as an entertainment for you in the contemplation of reading/understanding it, etc--often have the unfortunate effect of substituting for any other engagement in life. It is not clear to me that removing the books will necessarily force an improvement in the typical faux-intellectual's level of engagement with life however.

Reading much Shaw at any one time can quickly become exasperating however, and leads one to ask the question, O.K., so what did Shaw like? I was able to come up with three possible things that he seems not at least to have openly detested. 1. I remember reading somewhere that he liked Wendy Hiller , who acted in a lot of his plays, and was the female lead in the outstanding movie versions of Major Barbara and Pygmalion. She was very good at playing the humor, which she clearly "got", and without which watching a production of Shaw would be excruciating. 2. Music? His mother was one of those fanatical Dublin singers and music aficiondos whose passion led so far as to bring trouble to her domestic life, and Shaw's early writing career consisted largely of music criticism, so it was at least central to his view of life. He probably would not have liked this though. 3. Caesar, evidently, at least in that he writes his character as being a great deal like George Bernard Shaw himself, which is a high compliment from the pen of this author.

Reading much Shaw at any one time can quickly become exasperating however, and leads one to ask the question, O.K., so what did Shaw like? I was able to come up with three possible things that he seems not at least to have openly detested. 1. I remember reading somewhere that he liked Wendy Hiller , who acted in a lot of his plays, and was the female lead in the outstanding movie versions of Major Barbara and Pygmalion. She was very good at playing the humor, which she clearly "got", and without which watching a production of Shaw would be excruciating. 2. Music? His mother was one of those fanatical Dublin singers and music aficiondos whose passion led so far as to bring trouble to her domestic life, and Shaw's early writing career consisted largely of music criticism, so it was at least central to his view of life. He probably would not have liked this though. 3. Caesar, evidently, at least in that he writes his character as being a great deal like George Bernard Shaw himself, which is a high compliment from the pen of this author.Shaw loves to teach lessons and set people straight. Nowadays he would probably be the host of a talk radio program.

CLEOPATRA: "Those Roman helmets are so becoming." This is followed by a discussion of Caesar's baldness, which of course only someone with the mentality of a teenage girl would think important. Rules of playwriting for the entertainment of a bourgeois audience #1: Exploit any popular and easily recognized cliches your subject offers to the full (See Amadeus or any other popular biographical drama of a Great historical figure).

Saturday, April 25, 2009

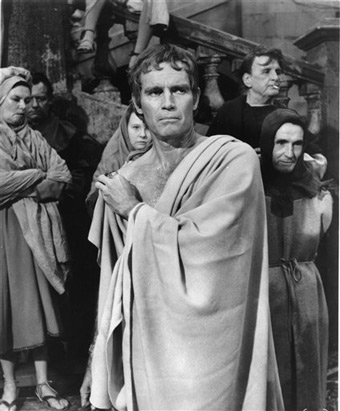

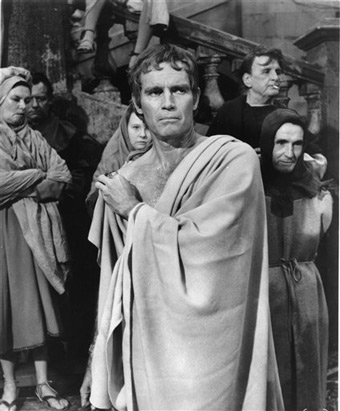

Julius Caesar--Shakespeare (Part 1)

Cleopatra of course isn't in this one. It was doubtless thrown in at this spot on my list source as a deceptive answer.

I had read it a couple of times, but not for many years, and never officially for this reading program I have made more or less my fate (which increasingly appears to have been not quite the right choice).

With reference to an earlier discussion on Gil Roth's site, this is, I am pretty sure, the 14th Shakespeare play I have read. In any case, if I have read more, I have no memory of them. There are quite a few big ones still out there.

I still find Julius Caesar a great, ebullient entertainment. It is not usually reputed by most maturer and more advanced readers among this author's first rank of work. I am more of a pass/fail reader than one of those who feels compelled to rank everything into very distinct gradations of quality. Life is short and potentially grisly enough, I think, and decidedly good or pretty things are rare enough occurrences even to one of a generally generous disposition, that if a book or anything else has ought of excellence in it, and no obvious deficiencies or uglinesses by the usual standards of human existence, I am more than delighted to have it.

This prevents me from attaining real connoisseurship or expertise in any field, I suppose, and allows the possibility that my pleasures and insights are cheaper, if not catastrophically so, then they otherwise might be. However, if I were to prove unable, or were to succumb to the idea that I were unable to properly comprehend, for example, Hamlet--which if I were to take someone like Harold Bloom's word for it (which obviously I don't), no one currently living, apart from himself, does, and the culture and language are greatly diminished for it--I would run the risk of becoming unable to find delight in anything, which has actually been a problem I have struggled with for some years.

This is the standard 10th grade English Shakespeare play in American high schools, which probably accounts for a good deal of the surprising lack of fervor for it I detect among large swathes of the current grown-up intelligentsia. The play does seem to lend itself, even in years long afterwards, to a sort of tenth-grade level interpretation no matter how much additional knowledge and experience you bring to the reading. As I was not at a tenth-grade level of reading or anything else when I was actually in tenth grade, at this late date it is not so much irritating, as it is moderately pleasant, to feel oneself having attained somewhat of that status of proper sophomorehood at last.

Many of my notes on this play are enigmas to me as I finally get ready to post my thoughts on it. I said--probably mouthed--"One can see it is the work of a man in the unfolding of construction, matter of fact language of introductory scene." Did I mean here man as opposed to woman? Or man as in man--mensch, philosopher-king, etc? If the first why did this strike me as important? We are talking about Shakespeare, it is hardly of interest that he wrote in some way characteristic of one sex, which he probably was, rather than another. I don't understand.

Cassius's famous speech at I.ii.135 ("Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world/Like a Colossus, and we petty men, etc...") demonstrates succintly why there had to be war; there were too many great (in the sense of largeness of presence and self-conception) men, independent men, spirited men, strong men, what have you, yet active to allow for a bloodless submission to Caesar. This is often the case during the origins and ascendencies of great peoples--this is where England considered itself to be in the 1590s incidentally, and with reason--but maturity and decline largely winnows such spirits as a percentage, almost even as an identifiable type, of the population.

Cassius's famous speech at I.ii.135 ("Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world/Like a Colossus, and we petty men, etc...") demonstrates succintly why there had to be war; there were too many great (in the sense of largeness of presence and self-conception) men, independent men, spirited men, strong men, what have you, yet active to allow for a bloodless submission to Caesar. This is often the case during the origins and ascendencies of great peoples--this is where England considered itself to be in the 1590s incidentally, and with reason--but maturity and decline largely winnows such spirits as a percentage, almost even as an identifiable type, of the population.

"One goes over every line not gotten because of the anticipation of its importance." I wrote this, and certainly I meant something by it, I was trying to express that the play was not in fact wholly dead to me, that there was something in it comprehensible that had resonance in my mental if not my visible and social life. It is still a conflicted and tortured relation to literature however.

II. i. 63-65 BRUTUS: "Between the acting of a dreadful thing

And the first motion, all the interim is

Like a phantasma or a hideous dream:"

"The Roman code of honor as painted by W.S. has 'universal' application...Tension of action/necessity--would have been avoided." More of my notations. I don't know what the second refers to. The first I think is the old bit that the Roman code of honor, or the chronicles of the Hebrews, or anything else that is a product of a particular society in a particular time, has lasting resonance and importance across time not in themselves and on account of their original purposes but because writers of genius caused the ideas in them to be formed as fundamental developments and ideals in the collective imagination.

"The Roman code of honor as painted by W.S. has 'universal' application...Tension of action/necessity--would have been avoided." More of my notations. I don't know what the second refers to. The first I think is the old bit that the Roman code of honor, or the chronicles of the Hebrews, or anything else that is a product of a particular society in a particular time, has lasting resonance and importance across time not in themselves and on account of their original purposes but because writers of genius caused the ideas in them to be formed as fundamental developments and ideals in the collective imagination.

Apparently at the time I read this play I was quoting from it in arguments with my wife, and seem to have especially proud of employing a variation of the "Upon what meat doth this Caesar feed/That he is grown so great..." speech in such a combat, which seems to have momentarily disarmed my tyrannic opponent, for the end of the note states with rare assurance, "Women love W.S."

II. ii. 30-33 CALPURNIA: "When beggars die, there are no comets seen,

The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes.

CAESAR: "Cowards die many times before their deaths;

The valiant never taste of death but once."

These are accurately expressed ideas, the real dint of which I need to try to impress upon my sons before they develop too strong a stake in death and cowardice.

"What is W.S.'s position regarding this action (the murder of Caesar)? Crowd is silly--Antony's rhetoric silly." Wow. That's a rather bold assertion for me. I guess I was thinking maybe he was subtly sympathetic with it.

"What is W.S.'s position regarding this action (the murder of Caesar)? Crowd is silly--Antony's rhetoric silly." Wow. That's a rather bold assertion for me. I guess I was thinking maybe he was subtly sympathetic with it.

Some other quickie observations:

Brutus sees Cassius as self-possessed, but himself as not.

Brutus shows concern on numerous occasions for the will of the people as opposed to the will of the conspirators.

Cassius's speeches denouncing Caesar nonetheless reveal grudging, perhaps even unconscious, acknowledgements of his leadership and other virtues.

Cassius laments that "Rome, thou hast lost the breed of noble bloods/When went there by an age, since the great flood/But it was famed with more than one man", though ironically, admittedly in large part due to the conspiracy, this age in the end produced more famous Romans than any other.

Caesar notes of Cassius that he cares not for representations of life (art, music, etc) and that this indicates danger.

I thought it noteworthy to state that this play is funnier than Coriolanus.

Whereas the greatness of Coriolanus is acknowledged throughout his play, that of Caesar is minimized. Caesar also appears more affected by the crowd. The ideas in this play are lighter. Life and death themselves are lighter.

Cleopatra of course isn't in this one. It was doubtless thrown in at this spot on my list source as a deceptive answer.

I had read it a couple of times, but not for many years, and never officially for this reading program I have made more or less my fate (which increasingly appears to have been not quite the right choice).

With reference to an earlier discussion on Gil Roth's site, this is, I am pretty sure, the 14th Shakespeare play I have read. In any case, if I have read more, I have no memory of them. There are quite a few big ones still out there.

I still find Julius Caesar a great, ebullient entertainment. It is not usually reputed by most maturer and more advanced readers among this author's first rank of work. I am more of a pass/fail reader than one of those who feels compelled to rank everything into very distinct gradations of quality. Life is short and potentially grisly enough, I think, and decidedly good or pretty things are rare enough occurrences even to one of a generally generous disposition, that if a book or anything else has ought of excellence in it, and no obvious deficiencies or uglinesses by the usual standards of human existence, I am more than delighted to have it.

This prevents me from attaining real connoisseurship or expertise in any field, I suppose, and allows the possibility that my pleasures and insights are cheaper, if not catastrophically so, then they otherwise might be. However, if I were to prove unable, or were to succumb to the idea that I were unable to properly comprehend, for example, Hamlet--which if I were to take someone like Harold Bloom's word for it (which obviously I don't), no one currently living, apart from himself, does, and the culture and language are greatly diminished for it--I would run the risk of becoming unable to find delight in anything, which has actually been a problem I have struggled with for some years.

This is the standard 10th grade English Shakespeare play in American high schools, which probably accounts for a good deal of the surprising lack of fervor for it I detect among large swathes of the current grown-up intelligentsia. The play does seem to lend itself, even in years long afterwards, to a sort of tenth-grade level interpretation no matter how much additional knowledge and experience you bring to the reading. As I was not at a tenth-grade level of reading or anything else when I was actually in tenth grade, at this late date it is not so much irritating, as it is moderately pleasant, to feel oneself having attained somewhat of that status of proper sophomorehood at last.

Many of my notes on this play are enigmas to me as I finally get ready to post my thoughts on it. I said--probably mouthed--"One can see it is the work of a man in the unfolding of construction, matter of fact language of introductory scene." Did I mean here man as opposed to woman? Or man as in man--mensch, philosopher-king, etc? If the first why did this strike me as important? We are talking about Shakespeare, it is hardly of interest that he wrote in some way characteristic of one sex, which he probably was, rather than another. I don't understand.

Cassius's famous speech at I.ii.135 ("Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world/Like a Colossus, and we petty men, etc...") demonstrates succintly why there had to be war; there were too many great (in the sense of largeness of presence and self-conception) men, independent men, spirited men, strong men, what have you, yet active to allow for a bloodless submission to Caesar. This is often the case during the origins and ascendencies of great peoples--this is where England considered itself to be in the 1590s incidentally, and with reason--but maturity and decline largely winnows such spirits as a percentage, almost even as an identifiable type, of the population.

Cassius's famous speech at I.ii.135 ("Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world/Like a Colossus, and we petty men, etc...") demonstrates succintly why there had to be war; there were too many great (in the sense of largeness of presence and self-conception) men, independent men, spirited men, strong men, what have you, yet active to allow for a bloodless submission to Caesar. This is often the case during the origins and ascendencies of great peoples--this is where England considered itself to be in the 1590s incidentally, and with reason--but maturity and decline largely winnows such spirits as a percentage, almost even as an identifiable type, of the population."One goes over every line not gotten because of the anticipation of its importance." I wrote this, and certainly I meant something by it, I was trying to express that the play was not in fact wholly dead to me, that there was something in it comprehensible that had resonance in my mental if not my visible and social life. It is still a conflicted and tortured relation to literature however.

II. i. 63-65 BRUTUS: "Between the acting of a dreadful thing

And the first motion, all the interim is

Like a phantasma or a hideous dream:"