What Literary Age (that I am not taking part in) Are We In Now?

Major literary periods in the English-speaking world run, it is well-established, in more or less 40-year cycles. Obviously there are instances of major writers of the prior era lingering into the new one, and transitional zones of a few years from time to time which appear to be devoid of much meaningful activity, but on the whole this pattern has been remarkably consistent. The exact start and end dates of the various periods differ slightly according to who is the commentator and what is their rationale. My own preferred dates, for the eras I am primarily familiar with, are as follows:

Elizabethan/Shakesperean: c.1580 (first efforts of Spenser & Sidney) to 1616 (death of Shakespeare). Sometimes the reign of James I (1603-25) is referred to as a distinctive Jacobin era, but I tend to regard the years up to Shakespeare's death as still dominated by the spirit of the Elizabethan generation.

Civil War/Miltonian Era: 1621 (publication of the Anatomy of Melancholy) to 1660. Paradise Lost, which was published in 1667, is a good example of a carryover from one period to another.

Restoration: 1660-1700 (death of Dryden). Not my favorite literary era. This was a golden age of science.

Augustan/Neo-Classical Era: 1702 (Ascension of Queen Anne, battle of Blenheim)--1744 (death of Pope).

Enlightenment/Age of Johnson: 1744 (publication of Life of Savage) to 1791 (Publication of Life of Johnson). These dates may run a little long. The start date could be pushed back to 1749 (Tom Jones) or 1750 (start of The Rambler) to keep the theory consistent.

Romantic: c.1795 (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Austen, et al begin writing) to 1832 (death of Scott). Most date the beginning of this era either to 1789 or 1798 (the publication of Lyrical Ballads). I think the earlier date is a little too early. In Germany the romantic era is sometimes said to have been kicked off at least as far back as the Sorrows of Werther in 1774.

Early Victorian/Dickensian: 1832 (first Tennyson poems) to 1870 (death of Dickens). Middlemarch, published in 1871, is kind of a last capstone to this era.

Late Victorian/Edwardian: 1871 (first Hardy novel, unification of Germany) to c. 1908 (rumblings of Modernity begin to grow substantial on all fronts). I've read a lot from this era over the last year or so. While I find the time period rather interesting as the bridge between the really pre-modern world and an environment and mindset that is fairly recognizable even now, it was kind of a bland time for literature. Even the acknowledged great writers of the period, such as Conrad and Henry James, are not terribly exciting and rather a chore to get through, and its renowned iconoclasts like Shaw and Oscar Wilde still wrote within a psychic and cultural atmosphere that seems very narrowly bound and static compared to everything which broke out at the end of the period.

Modernism: 1910-1948. Probably overall the most influential period as far as my own life goes. I chose '48 as the closing date for a variety of reasons. First off, with the Soviets solidifying their position everywhere in Eastern Europe and the economies of the West and the United States in particular stabilizing and beginning their long periods of sustained growth, the proclamation of Israel and the beginnings of decolonization elsewhere, etc, the very different postwar world began to take recognizable shape. Secondly T.S. Eliot won the Nobel Prize that year, which was a symbolic acknowledgement of the triumph of the class of writing and the generation of writers he represented, most of the major figures of which were however already dead or past their prime by 1948.

Postmodernism: 1951 (Waiting For Godot, The Catcher in the Rye) to 1989 (death of Samuel Beckett, collapse of Communism). The Catcher in the Rye is not a characteristically postmodern book, but worldwide it was probably the most representative American book throughout the period and I think it played an influential role in the time's overall cultural imagination akin to that which Werther did during the Romantic era. Samuel Beckett, a figure with whom I have been fascinated for many years, was an embodiment of a strain of old style European bohemianism and deep humanistic learning as the core of life the transmission of which does not seem to have survived the second world war either in the (post-Soviet) East or the West. The collapse of Communist Europe, along with other factors of course, accelerated the emerging globalization trend by several degrees. As I have mentioned elsewhere, nowadays when I take up a movie or a book even from the late 1980s and even the early 90s, the life in it, especially in foreign works but in American ones too to a certain extent, frequently feels like something almost out of the quaint ancestral past.

The New Age: 1992 (Ascension of postwar Baby Boomers to dominant political and economic power across the West) to approx. 2030. So clearly whatever is going on now we are right in the middle of it, judging by the trend of the past we may even already be a few years past the cycle's most fervent & intense manifestation. So what is it? I don't know. This era feels to many people like it is very weak in all of the traditional arts, but of course most people experienced the 50s, which produced plenty of interesting and outstanding stuff, as culturally insipid, and the mainstream literary world in the 1920s considered Galsworthy and Sinclair Lewis and Booth Tarkington and Michael Arlen and people like that to be the major writers of the day, so it is likely that if by some miracle I have grandchild who is both with-it and intelligent he or she will be able to amuse his bohemian friends with tales of how benighted his earnest bourgeois grandfather was. However, I will offer a few theories:

The seed of any identifiable era's dominant tenor is usually found to be the fulfillment in one way or another of the most inisistently proclaimed desires of the previous era; the best eras, like the Romantic and Modernist periods, occur when the addressed desires take on a form that was wholly unforeseen by the articulators of those desires. To speak of the most recent periods, the main wish of the Modernist period, as far as I can deduce, was an ever more extreme, even self-cannibalising modernism, which the postmodern writers did their best to deliver. The strongest desires to emerge from the postmodern period, to my view, were the desire for the critic and scholar/theorist to emerge triumphant over the author and 'art', which could certainly be said to have happened to a certain degree, and the desire for more diversity in terms of race, gender, geography, culture, etc, at the center of the literary world, which also seems to be an identifiable phenomenon, though with the exception of the ascendance of women writers less so within the U.S. than internationally. The current desire, which I expect to manifest itself after 2030, is for literature to address what it means in the internet age, respond to the decline of the author, and the possible death, for all intents, etc, of the book.

My desire, and since I have it I presume it must be widespread, is for the artistic ethos in some kind of identifiable form to reassert itself, and I expect this to happen as well. I was reading one of those status-oriented blogs not long ago where the community was obsessed about IQs and where people went to school and careers and bashing humanities majors as morons who lack the intellect to succeed in anything serious and so on, and I wrote a brief comment to the effect of "doesn't anybody want to be an artist anymore?" Even reading about scenes and people I probably would have hated, like Berkeley in the 60s, the passion and vim and assuredness and instinct for fully indulging in the artistic gesture is enough to make one want to cry when confronted with the completely algorithim-directed and economics-dominated life most of us have to live now. At the moment, any kind of naive artistic instinct operating with something akin to abandon, doesn't seem to exist. I like the middle class kids in Brooklyn giving some semblance of the bohemian life a try today, and I often wish I were a little younger and could join them, but when it comes to making or living art in a natural and unaffected way, it just isn't coming yet. I believe it will come again, that the current intensity and extreme competitiveness of economic, academic and social life will at some point break and the artistic sensibility will be re-awakened, and I think it will be wonderful and the culture will feel very invigorated by this energy. That is my prediction.

As a closing note I am going to link to some videos by a current Brooklyn-based music group that I kind of like, Elizabeth and the Catapult. Elizabeth is good-looking, obviously pretty intelligent, and she seems to straddle the line, albeit narrowly, between being endearing in her progressivism and social correctness, and the alternative--in short, the type I once imagined I would spend a lot of time hanging out with in my twenties in New York or some other interesting place. Still, in the end, they fail. They aren't interesting, one feels they lack conviction, that they have nothing to say, or rather that there is nothing within them that they are willing to reveal.

There was another song of theirs that I thought was very good in spite of all these shortcomings but I can't seem to find it now.

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

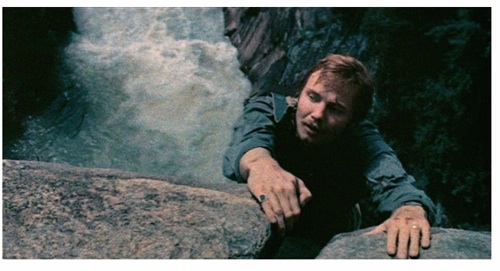

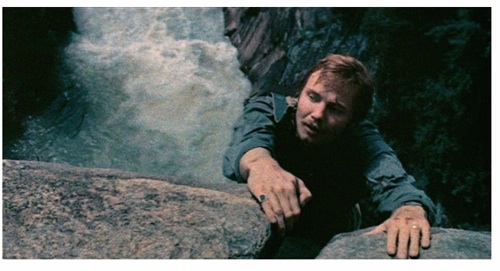

Deliverance 3

The emphasis on our (postmodern man's) being out of touch with our bodies, while it seems to be a ubiquitous theme throughout the culture, is more obsessively pursued here than it is in most discourses which take up the subject. I generally think this problem is overstated; that is, it would be my position that our intellects and spirits, relation to language and art and reason and so on, being equally out of sync, and all of these estrangements being problems and deficiencies of the mind above all, that a hyper-increased physicality in itself is unlikely to restore one to a more interesting or complete sense of self.

The emphasis on our (postmodern man's) being out of touch with our bodies, while it seems to be a ubiquitous theme throughout the culture, is more obsessively pursued here than it is in most discourses which take up the subject. I generally think this problem is overstated; that is, it would be my position that our intellects and spirits, relation to language and art and reason and so on, being equally out of sync, and all of these estrangements being problems and deficiencies of the mind above all, that a hyper-increased physicality in itself is unlikely to restore one to a more interesting or complete sense of self.

p.184: "I was aided by a totally different sense of touch than I had ever had, and it occurred to me that I must have developed it on the cliff." The book has a great belief in unrealized abilities that the circumstances of contemporary life have dulled in us, but that necessity, or adversity, could awaken if we found or put ourselves in a position to experience it. I do believe that when literal survival is at stake, such as in war, that something of this hyperacute awareness and sensibility does instinctively arise, and perhaps these realizations insinuate themselves permanently into consciousness. It is not my impression however that they contribute substantially to a permanent strength of mind if the foundation for such a mind be not already in place.

I interpret the story as supposed to be ultimately uplifting when the main character, Gentry, discovers his power to kill. I was taken along for some ways by this idea, though I was concerned about my health and mental fitness. Among the book's other main lessons is that somebody has to be in charge, has to take charge, and of course in the state of nature or even sometimes in advanced stages of civilization that often involves having to be willing to kill someone.

"Cornholed". There's a nice word. "...a man who had held a gun on it while another one cornholed him..."

The primal energy of the water was remarked upon numerous times. The means writers make of and the importance they attach to water symbolism--and almost all do--is the intellectual equivalent of Gentry's heightened sense of touch when scrambling for his life up the rocks. It ought to be second nature to a properly developed and highly functioning intellect.

The book on the whole, believe it or not, is very understated (quiet, modest, etc).

I wonder how these guys would have handled 3rd world immigration. Probably not well.

The emphasis on our (postmodern man's) being out of touch with our bodies, while it seems to be a ubiquitous theme throughout the culture, is more obsessively pursued here than it is in most discourses which take up the subject. I generally think this problem is overstated; that is, it would be my position that our intellects and spirits, relation to language and art and reason and so on, being equally out of sync, and all of these estrangements being problems and deficiencies of the mind above all, that a hyper-increased physicality in itself is unlikely to restore one to a more interesting or complete sense of self.

The emphasis on our (postmodern man's) being out of touch with our bodies, while it seems to be a ubiquitous theme throughout the culture, is more obsessively pursued here than it is in most discourses which take up the subject. I generally think this problem is overstated; that is, it would be my position that our intellects and spirits, relation to language and art and reason and so on, being equally out of sync, and all of these estrangements being problems and deficiencies of the mind above all, that a hyper-increased physicality in itself is unlikely to restore one to a more interesting or complete sense of self.p.184: "I was aided by a totally different sense of touch than I had ever had, and it occurred to me that I must have developed it on the cliff." The book has a great belief in unrealized abilities that the circumstances of contemporary life have dulled in us, but that necessity, or adversity, could awaken if we found or put ourselves in a position to experience it. I do believe that when literal survival is at stake, such as in war, that something of this hyperacute awareness and sensibility does instinctively arise, and perhaps these realizations insinuate themselves permanently into consciousness. It is not my impression however that they contribute substantially to a permanent strength of mind if the foundation for such a mind be not already in place.

I interpret the story as supposed to be ultimately uplifting when the main character, Gentry, discovers his power to kill. I was taken along for some ways by this idea, though I was concerned about my health and mental fitness. Among the book's other main lessons is that somebody has to be in charge, has to take charge, and of course in the state of nature or even sometimes in advanced stages of civilization that often involves having to be willing to kill someone.

"Cornholed". There's a nice word. "...a man who had held a gun on it while another one cornholed him..."

The primal energy of the water was remarked upon numerous times. The means writers make of and the importance they attach to water symbolism--and almost all do--is the intellectual equivalent of Gentry's heightened sense of touch when scrambling for his life up the rocks. It ought to be second nature to a properly developed and highly functioning intellect.

The book on the whole, believe it or not, is very understated (quiet, modest, etc).

I wonder how these guys would have handled 3rd world immigration. Probably not well.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Some Movies From the 80s & 90s That Are Supposed to be Great

Nothing subversive here. Nothing especially exciting here either, even to me.

Howards End (1992)

I saw this back when it first came out and thought it was solidly good, no grounds for me to give reproach at the very least. Seeing it again 17 or 18 years later, something about it seemed a little more off--such as none of the characters or the world they inhabit seeming believable any longer. This is in part the fault of the book, which I have happened to read in the interval, and which the movie follows pretty closely (and which shares many of the problems I now sense with the movie). The scope of the story seems too narrow and the lives depicted too constricted to make the points it wants to make. There are a lot of symbols of the desire and inner lives of the characters but in the movie these symbols never acquire the animating spirit they need from the characters to achieve realisation.

I wrote the above paragraph late last night. Looking at it now it strikes me that the concern with the story's scope, or smallness, is a very middle class college-educated American's way of critiquing literature, especially. I read a piece characteristic of this mindset recently by one such (presumably middle-class) product of a pre-revolutionary 60s humanities education, a writer named Steven Millhouser whose books have received generally good notice, including a Pulitzer Prize I think, but does not seem either to be much read or to be considered in the ranks of major authors. To get back to the main point, in this story the narrator has a dream of being taken though an endless enormous library which contains all the lost books of antiquity, such as the 150 lost plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles, all the volumes lost in the fire at Alexandria, the missing works of Aristotle, etc (one of the humorists among the students at my college opined that there was doubtless a lost treatise "On Doggy Style", that had been destroyed by monks into whose hands it had fallen in the middle ages); the lost epic poems of the early Middle Ages; the endings of various unfinished works such as Don Juan, Edwin Drood and The Castle; The later works of great authors who died early; ambitious works planned but never written, such as Milton's planned epic poem about the Arthurian legends; books about Don Quixote's childhood or Hamlet's years at the university; not to mention all the millions of books that were written and have been forgotten. Eventually the gimmick was carried too far, but for a while it was effective in making one consider the hopeless pointlessness and insignificance of writing anything. Most English writers of the past century don't seem to have been too oppressed by such worries. They also seem to have a different, and more natural attitude towards writing and the work of making literature than the more strident and earnest model that has prevailed in America. It is sometimes stated that England has not produced a 'major' novelist--major in the sense of depicting a kind of totality of life and experience--since Dickens, which may be true in the most stringent sense, which I suppose is the only one I ought to care about. But on the whole the limited and more finely focused scope has served many English writers well over the last century or so, and Forster is very much a writer in this vein.

The movie is still technically very well made. The pacing is smooth, and I noticed several times, a specific example of which I unfortunately can't remember, that the camera had been unobtrusively placed in a position that was not the obvious place for it but which greatly improved the effect of the scene.

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

I had never seen this before. I wasn't overly excited to see it, though I suspected I might be taken in by it, as Steven Spielberg is famous for his ability to manipulate the masses, even those who should know better, but, to my surprise, I had a hard time getting through it. In fact I couldn't get through it on my own, and it was only when I let my older sons watch the last two-thirds of it with it that I could finish it, and with some pleasure. I am not a knee-jerk Spielberg basher. As almost everyone knows, he does some things extremely well, and other things, usually those involving some level of acceptable intellectual sophistication, not so well, but I am not the kind to hold that against. This movie, I know, is just a sweet kids' film, but I found quite slow and hard to pay attention to.

It is my impression that this movie, which was a huge hit when first released, is not as well known today. My children, who now that they are in school hear all about everything, had never heard of it, and while I think they enjoyed being able to watch a movie with me and were interested in various things that were going on, neither has mentioned it since, and they are at the age where if something makes an impression on them they talk about it incessantly for weeks and months afterwards. I would not rate it as one of the master's better efforts.

Babette's Feast and Au Revoir, Les Enfants (both 1987)

Babette's Feast and Au Revoir, Les Enfants (both 1987)

I am putting these together because they have a number of things in common which interest me. Obviously both were made in the same year. Although Babette is a Danish movie, there is a good deal of Frenchness interlarded in it. Both are set in an earlier time, Babette from approximately the 1830s-70s, and Au Revoir in World War II. Most importantly both are well-steeped in, and to a certain extent take for granted, though not wholly unself-consciously, what we think of as the traditional European culture. Christianity and its traditions are a ubiquitous force in life, regardless of whether the filmmakers are believers themselves, young people are drilled in Euclid and study serious music, the rituals of meals and tea that date back for centuries are observed with attentiveness. The directors, Gabriel Axel (b. 1918) and Louis Malle (b.1932) both had some experience of life before World War II and were well into adulthood before the tumults of the 60s and the more international and high tech society of the last 30 years especially--to say nothing of post-1990 mass immigration and globalization--began eroding the longstanding ways and characters of the ancient nations of Europe. I note this because while 1987 is not that long ago, this generation of filmmakers and artists has passed on, and I do not see the same cultural sensibility at all in the films of the last 15 years especially, with regard to religion, music, literature or other intellectual achievements, in some instances, as I pointed out in my bit about The Best of Youth, even the national film legacy. This is what Americans are getting at when they say that Europe is Dead. The feeling that there is a profound link to the past, to civilization, that our sensitive types have been accustomed to looking to Europeans for, seems not to be there anymore, and we (or at the very, very least I) find we are taking this role on ourselves with regard to our own more recent but still somewhat distinguished and relevant history.

I was actually dreading Babette's Feast, but it was better than I thought it was going to be. While I do love eating French meals, listening to people talk about French meals in a self-satisfied manner--French people especially--I find rather tiresome, and my impression was that that was what this movie was largely about. But in fact it is mainly about severe Scandanavians who are determined to resist earthly pleasures, which was a theme that appeals to me much more. While I am not of such a disciplined cast myself, I might as well be for all the sensualism I actually have indulged in over the years.

I was actually dreading Babette's Feast, but it was better than I thought it was going to be. While I do love eating French meals, listening to people talk about French meals in a self-satisfied manner--French people especially--I find rather tiresome, and my impression was that that was what this movie was largely about. But in fact it is mainly about severe Scandanavians who are determined to resist earthly pleasures, which was a theme that appeals to me much more. While I am not of such a disciplined cast myself, I might as well be for all the sensualism I actually have indulged in over the years.

I used to think that someday before I died I wanted to go to one of these world class French restaurants and have, once, one of these incredible seven course meals. This was largely presuming my developing into a different person however, and, not having been abroad or been to any kind of serious restaurant now in nearly 10 years due to my having so children it simply does not seem realistic anymore. I don't have the practice eating in quality places, having quality drinks and so on, and while up to about age 30 I was kind of on a trajectory to not be terribly out of place in such establishments, but I have fallen off that badly now and at this point the whole idea seems kind of unrealistic, barring a Tony Bennett-like resurrection of my general culturedness in middle age.

Au Revoir Les Enfants is a good movie, and I would recommend it to anybody who wants to see a well made, sensitive film and does not require a lot of provocation or outrage with the experience. I think I might have seen it before, 20 years ago, but I had largely forgotten it, or gotten it confused with Europa, Europa, which is also about a Jewish schoolboy trying to wait out the war by posing as a gentile, though that one, which I also don't remember well, was set in the east. I have a weakness for both school movies and movies that depict Catholic priests as genuinely intelligent and decent men, and this satisfies both of those impulses, so I like it.

Au Revoir Les Enfants is a good movie, and I would recommend it to anybody who wants to see a well made, sensitive film and does not require a lot of provocation or outrage with the experience. I think I might have seen it before, 20 years ago, but I had largely forgotten it, or gotten it confused with Europa, Europa, which is also about a Jewish schoolboy trying to wait out the war by posing as a gentile, though that one, which I also don't remember well, was set in the east. I have a weakness for both school movies and movies that depict Catholic priests as genuinely intelligent and decent men, and this satisfies both of those impulses, so I like it.

Nothing subversive here. Nothing especially exciting here either, even to me.

Howards End (1992)

I saw this back when it first came out and thought it was solidly good, no grounds for me to give reproach at the very least. Seeing it again 17 or 18 years later, something about it seemed a little more off--such as none of the characters or the world they inhabit seeming believable any longer. This is in part the fault of the book, which I have happened to read in the interval, and which the movie follows pretty closely (and which shares many of the problems I now sense with the movie). The scope of the story seems too narrow and the lives depicted too constricted to make the points it wants to make. There are a lot of symbols of the desire and inner lives of the characters but in the movie these symbols never acquire the animating spirit they need from the characters to achieve realisation.

I wrote the above paragraph late last night. Looking at it now it strikes me that the concern with the story's scope, or smallness, is a very middle class college-educated American's way of critiquing literature, especially. I read a piece characteristic of this mindset recently by one such (presumably middle-class) product of a pre-revolutionary 60s humanities education, a writer named Steven Millhouser whose books have received generally good notice, including a Pulitzer Prize I think, but does not seem either to be much read or to be considered in the ranks of major authors. To get back to the main point, in this story the narrator has a dream of being taken though an endless enormous library which contains all the lost books of antiquity, such as the 150 lost plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles, all the volumes lost in the fire at Alexandria, the missing works of Aristotle, etc (one of the humorists among the students at my college opined that there was doubtless a lost treatise "On Doggy Style", that had been destroyed by monks into whose hands it had fallen in the middle ages); the lost epic poems of the early Middle Ages; the endings of various unfinished works such as Don Juan, Edwin Drood and The Castle; The later works of great authors who died early; ambitious works planned but never written, such as Milton's planned epic poem about the Arthurian legends; books about Don Quixote's childhood or Hamlet's years at the university; not to mention all the millions of books that were written and have been forgotten. Eventually the gimmick was carried too far, but for a while it was effective in making one consider the hopeless pointlessness and insignificance of writing anything. Most English writers of the past century don't seem to have been too oppressed by such worries. They also seem to have a different, and more natural attitude towards writing and the work of making literature than the more strident and earnest model that has prevailed in America. It is sometimes stated that England has not produced a 'major' novelist--major in the sense of depicting a kind of totality of life and experience--since Dickens, which may be true in the most stringent sense, which I suppose is the only one I ought to care about. But on the whole the limited and more finely focused scope has served many English writers well over the last century or so, and Forster is very much a writer in this vein.

The movie is still technically very well made. The pacing is smooth, and I noticed several times, a specific example of which I unfortunately can't remember, that the camera had been unobtrusively placed in a position that was not the obvious place for it but which greatly improved the effect of the scene.

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)I had never seen this before. I wasn't overly excited to see it, though I suspected I might be taken in by it, as Steven Spielberg is famous for his ability to manipulate the masses, even those who should know better, but, to my surprise, I had a hard time getting through it. In fact I couldn't get through it on my own, and it was only when I let my older sons watch the last two-thirds of it with it that I could finish it, and with some pleasure. I am not a knee-jerk Spielberg basher. As almost everyone knows, he does some things extremely well, and other things, usually those involving some level of acceptable intellectual sophistication, not so well, but I am not the kind to hold that against. This movie, I know, is just a sweet kids' film, but I found quite slow and hard to pay attention to.

It is my impression that this movie, which was a huge hit when first released, is not as well known today. My children, who now that they are in school hear all about everything, had never heard of it, and while I think they enjoyed being able to watch a movie with me and were interested in various things that were going on, neither has mentioned it since, and they are at the age where if something makes an impression on them they talk about it incessantly for weeks and months afterwards. I would not rate it as one of the master's better efforts.

Babette's Feast and Au Revoir, Les Enfants (both 1987)

Babette's Feast and Au Revoir, Les Enfants (both 1987)I am putting these together because they have a number of things in common which interest me. Obviously both were made in the same year. Although Babette is a Danish movie, there is a good deal of Frenchness interlarded in it. Both are set in an earlier time, Babette from approximately the 1830s-70s, and Au Revoir in World War II. Most importantly both are well-steeped in, and to a certain extent take for granted, though not wholly unself-consciously, what we think of as the traditional European culture. Christianity and its traditions are a ubiquitous force in life, regardless of whether the filmmakers are believers themselves, young people are drilled in Euclid and study serious music, the rituals of meals and tea that date back for centuries are observed with attentiveness. The directors, Gabriel Axel (b. 1918) and Louis Malle (b.1932) both had some experience of life before World War II and were well into adulthood before the tumults of the 60s and the more international and high tech society of the last 30 years especially--to say nothing of post-1990 mass immigration and globalization--began eroding the longstanding ways and characters of the ancient nations of Europe. I note this because while 1987 is not that long ago, this generation of filmmakers and artists has passed on, and I do not see the same cultural sensibility at all in the films of the last 15 years especially, with regard to religion, music, literature or other intellectual achievements, in some instances, as I pointed out in my bit about The Best of Youth, even the national film legacy. This is what Americans are getting at when they say that Europe is Dead. The feeling that there is a profound link to the past, to civilization, that our sensitive types have been accustomed to looking to Europeans for, seems not to be there anymore, and we (or at the very, very least I) find we are taking this role on ourselves with regard to our own more recent but still somewhat distinguished and relevant history.

I was actually dreading Babette's Feast, but it was better than I thought it was going to be. While I do love eating French meals, listening to people talk about French meals in a self-satisfied manner--French people especially--I find rather tiresome, and my impression was that that was what this movie was largely about. But in fact it is mainly about severe Scandanavians who are determined to resist earthly pleasures, which was a theme that appeals to me much more. While I am not of such a disciplined cast myself, I might as well be for all the sensualism I actually have indulged in over the years.

I was actually dreading Babette's Feast, but it was better than I thought it was going to be. While I do love eating French meals, listening to people talk about French meals in a self-satisfied manner--French people especially--I find rather tiresome, and my impression was that that was what this movie was largely about. But in fact it is mainly about severe Scandanavians who are determined to resist earthly pleasures, which was a theme that appeals to me much more. While I am not of such a disciplined cast myself, I might as well be for all the sensualism I actually have indulged in over the years.I used to think that someday before I died I wanted to go to one of these world class French restaurants and have, once, one of these incredible seven course meals. This was largely presuming my developing into a different person however, and, not having been abroad or been to any kind of serious restaurant now in nearly 10 years due to my having so children it simply does not seem realistic anymore. I don't have the practice eating in quality places, having quality drinks and so on, and while up to about age 30 I was kind of on a trajectory to not be terribly out of place in such establishments, but I have fallen off that badly now and at this point the whole idea seems kind of unrealistic, barring a Tony Bennett-like resurrection of my general culturedness in middle age.

Au Revoir Les Enfants is a good movie, and I would recommend it to anybody who wants to see a well made, sensitive film and does not require a lot of provocation or outrage with the experience. I think I might have seen it before, 20 years ago, but I had largely forgotten it, or gotten it confused with Europa, Europa, which is also about a Jewish schoolboy trying to wait out the war by posing as a gentile, though that one, which I also don't remember well, was set in the east. I have a weakness for both school movies and movies that depict Catholic priests as genuinely intelligent and decent men, and this satisfies both of those impulses, so I like it.

Au Revoir Les Enfants is a good movie, and I would recommend it to anybody who wants to see a well made, sensitive film and does not require a lot of provocation or outrage with the experience. I think I might have seen it before, 20 years ago, but I had largely forgotten it, or gotten it confused with Europa, Europa, which is also about a Jewish schoolboy trying to wait out the war by posing as a gentile, though that one, which I also don't remember well, was set in the east. I have a weakness for both school movies and movies that depict Catholic priests as genuinely intelligent and decent men, and this satisfies both of those impulses, so I like it.My main observation on this movie is that I wonder, as more years go by, and the Nazi era fades wholly from living memory, if people will be able to find it believable, or wonder if certain aspects of it have not been exaggerated. In this movie for example, the main tension, is that the school is sheltering several Jewish boys who are pretending to be Christians. The boys in question are 11-12 years old, and I admit that I found myself saying, is it really plausible that the Nazis are going to devote all this energy to tracking down and imprisoning a handful of children? And when they are losing the war to boot? And I know that it actually happened, but from the viewpoint of the world as we know it today, it does not make any sense, even acknowledging that they hate the children and want to kill them, from our position it's a waste of resources, not to mention that any official policy involving cruelty towards children, though not uncommon even in this country until the last 40-50 years, is just unfathomable to us. I think if trends of acceptable attitudes continue as they are, the Nazi history will become something that people have a hard time really believing, and will tend to presume it either has been exaggerated or is not anyhow relevant to them, in the same way that we don't get worked up about the atrocities committed by the ancient Persians or Romans.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Summer Pictures, New Hampshire

A few leftovers from the end of August. Self-explanatory

Self-explanatory

The same party, a few minutes later

The same party, a few minutes later

Newfound Lake, Wellington State Park, Bristol, NH. This lake is usually very crowded, so in my original posting I mistook for another, less-popular, man-made lake near a dam that we go to, but when I made it bigger I noticed the duck and the houses visible on the opposite shore and realized that this was actually Newfound, and somehow we had gotten a picture without any other people in it.

Newfound Lake, Wellington State Park, Bristol, NH. This lake is usually very crowded, so in my original posting I mistook for another, less-popular, man-made lake near a dam that we go to, but when I made it bigger I noticed the duck and the houses visible on the opposite shore and realized that this was actually Newfound, and somehow we had gotten a picture without any other people in it.

A few leftovers from the end of August.

Self-explanatory

Self-explanatory The same party, a few minutes later

The same party, a few minutes later Newfound Lake, Wellington State Park, Bristol, NH. This lake is usually very crowded, so in my original posting I mistook for another, less-popular, man-made lake near a dam that we go to, but when I made it bigger I noticed the duck and the houses visible on the opposite shore and realized that this was actually Newfound, and somehow we had gotten a picture without any other people in it.

Newfound Lake, Wellington State Park, Bristol, NH. This lake is usually very crowded, so in my original posting I mistook for another, less-popular, man-made lake near a dam that we go to, but when I made it bigger I noticed the duck and the houses visible on the opposite shore and realized that this was actually Newfound, and somehow we had gotten a picture without any other people in it.

Summer Pictures, Connecticut II

Now that I have a digital camera and take 275 pictures every time I leave the house, rather than poring over them and picking out 10 "best" ones, I am experimenting with posting a random selection based on some number games of my own devising. Anything that is egregiously bad I don't include, but otherwise the sample should give a reasonable idea of the story I am trying to relate. One thing I notice is that compared to other people I almost never take restaurant/eating pictures, especially pictures of the food. One can easily overdo this, but sometimes I do find it of interest to see where other people go and what they are eating. A lot of people also take a lot of on-the-road shots, highways, signs, rest areas, which I also find I like a little of in a travel narrative, though I usually forget to take such pictures myself. This is all a roundabout way of explaining why this second batch of pictures is rather dull.

1. The Connecticut State Heroine, Prudence Crandall, and Her Student. Prudence Crandall ran a girls' school somewhere in Connecticut, I forget exactly what town, to which in 1833 she admitted a single black student, sending the local community into convulsions. When Crandall refused their demands that this student be put out of the school, she was briefly imprisoned. Shortly thereafter the school was shut down and Crandall ended up going to the Kansas/Nebraska area, never returning to Connecticut. Now she is the official state heroine there, which honor I do not think exists in every state. This monument is a very recent addition, supposedly the result of a campaign by the enlightened schoolchildren of the state, who objected to state hero Nathan Hale's having a fine statue of himself in the capitol building while his feminine counterpart had no such commemoration.

1. The Connecticut State Heroine, Prudence Crandall, and Her Student. Prudence Crandall ran a girls' school somewhere in Connecticut, I forget exactly what town, to which in 1833 she admitted a single black student, sending the local community into convulsions. When Crandall refused their demands that this student be put out of the school, she was briefly imprisoned. Shortly thereafter the school was shut down and Crandall ended up going to the Kansas/Nebraska area, never returning to Connecticut. Now she is the official state heroine there, which honor I do not think exists in every state. This monument is a very recent addition, supposedly the result of a campaign by the enlightened schoolchildren of the state, who objected to state hero Nathan Hale's having a fine statue of himself in the capitol building while his feminine counterpart had no such commemoration.

2. View of the Rotunda. This statue is called "The Genius of Connecticut". It is large and bronze and occupies the center of the building's rotunda. It is a replica of an older statue which used to stand atop the dome but was removed after being damaged in the hurricane of 1938 and melted down during World War II. There is evidently a plan to eventually put this statue on top of the dome as well; at the moment they can't afford it.

2. View of the Rotunda. This statue is called "The Genius of Connecticut". It is large and bronze and occupies the center of the building's rotunda. It is a replica of an older statue which used to stand atop the dome but was removed after being damaged in the hurricane of 1938 and melted down during World War II. There is evidently a plan to eventually put this statue on top of the dome as well; at the moment they can't afford it.

3. I believe this is a much smaller cast of the "Genius".

3. I believe this is a much smaller cast of the "Genius".

Now that I have a digital camera and take 275 pictures every time I leave the house, rather than poring over them and picking out 10 "best" ones, I am experimenting with posting a random selection based on some number games of my own devising. Anything that is egregiously bad I don't include, but otherwise the sample should give a reasonable idea of the story I am trying to relate. One thing I notice is that compared to other people I almost never take restaurant/eating pictures, especially pictures of the food. One can easily overdo this, but sometimes I do find it of interest to see where other people go and what they are eating. A lot of people also take a lot of on-the-road shots, highways, signs, rest areas, which I also find I like a little of in a travel narrative, though I usually forget to take such pictures myself. This is all a roundabout way of explaining why this second batch of pictures is rather dull.

1. The Connecticut State Heroine, Prudence Crandall, and Her Student. Prudence Crandall ran a girls' school somewhere in Connecticut, I forget exactly what town, to which in 1833 she admitted a single black student, sending the local community into convulsions. When Crandall refused their demands that this student be put out of the school, she was briefly imprisoned. Shortly thereafter the school was shut down and Crandall ended up going to the Kansas/Nebraska area, never returning to Connecticut. Now she is the official state heroine there, which honor I do not think exists in every state. This monument is a very recent addition, supposedly the result of a campaign by the enlightened schoolchildren of the state, who objected to state hero Nathan Hale's having a fine statue of himself in the capitol building while his feminine counterpart had no such commemoration.

1. The Connecticut State Heroine, Prudence Crandall, and Her Student. Prudence Crandall ran a girls' school somewhere in Connecticut, I forget exactly what town, to which in 1833 she admitted a single black student, sending the local community into convulsions. When Crandall refused their demands that this student be put out of the school, she was briefly imprisoned. Shortly thereafter the school was shut down and Crandall ended up going to the Kansas/Nebraska area, never returning to Connecticut. Now she is the official state heroine there, which honor I do not think exists in every state. This monument is a very recent addition, supposedly the result of a campaign by the enlightened schoolchildren of the state, who objected to state hero Nathan Hale's having a fine statue of himself in the capitol building while his feminine counterpart had no such commemoration. 2. View of the Rotunda. This statue is called "The Genius of Connecticut". It is large and bronze and occupies the center of the building's rotunda. It is a replica of an older statue which used to stand atop the dome but was removed after being damaged in the hurricane of 1938 and melted down during World War II. There is evidently a plan to eventually put this statue on top of the dome as well; at the moment they can't afford it.

2. View of the Rotunda. This statue is called "The Genius of Connecticut". It is large and bronze and occupies the center of the building's rotunda. It is a replica of an older statue which used to stand atop the dome but was removed after being damaged in the hurricane of 1938 and melted down during World War II. There is evidently a plan to eventually put this statue on top of the dome as well; at the moment they can't afford it. 3. I believe this is a much smaller cast of the "Genius".

3. I believe this is a much smaller cast of the "Genius".

Summer Pictures, Connecticut I

I have been driving across Connecticut 8-10 times a year for most of the last two decades without ever stopping for much more than the occasional hour, so when I had a short four day vacation coming to me in August I decided to go down there for a couple of days as a change from routine. We stayed at a hotel on the Berlin Turnpike in Berlin, about 10 miles south of Hartford, and close to the front line where "New England" in the cultural sense comes to an end and the "New York" homeland, which encroaches a little farther into Connecticut every few years, begins to be predominate. My sense was that we were still pretty squarely on the New England side, though in the way that Alsace is decidedly a part of France while having much more in common with Germany than for example the Loire Valley.

1. Scenic Vista, Devil's Hopyard State Park, East Haddam. This was another recommendation from my 1966 (which I sometime mistakenly refer to as my 1962) encyclopedia, and it was a modest but pleasant site, some mild hiking and a waterfall, as well as a campground. I thought this view had an especially colonial, or maybe an infancy-of-the-republic look about it. Though this is the Connecticut River Valley--itself one of the most idyllic stretches of land I am familiar with--it calls to my mind the spirits of Washington Irving and some of the painters of the Hudson River School.

1. Scenic Vista, Devil's Hopyard State Park, East Haddam. This was another recommendation from my 1966 (which I sometime mistakenly refer to as my 1962) encyclopedia, and it was a modest but pleasant site, some mild hiking and a waterfall, as well as a campground. I thought this view had an especially colonial, or maybe an infancy-of-the-republic look about it. Though this is the Connecticut River Valley--itself one of the most idyllic stretches of land I am familiar with--it calls to my mind the spirits of Washington Irving and some of the painters of the Hudson River School.

The affluent town of East Haddam with its antique but still functioning riverside opera house, remains safely within the boundaries of New England. The area around it for a good 15-20 miles in every direction was surprisingly rural, twisting two lane roads, no regular (i.e., non-boutique) hotels, few restaurants. I had originally planned to stay nearer to the park, but the closest hotels were a half an hour away, and these appeared to be or belonged to chains which in our advancing age we consider to be substandard; so we ended up staying closer to Hartford on a busy and somewhat built up though not suffocating stretch of state/U.S. highway where we were able to eat and shop for supplies and of which I grew rather fond by the end of three days.

2. Dome of the State House, Hartford. We also went to Mark Twain's house while we were in town, but that was evidently so much fun that we forgot to take pictures--it has been a long time since we have been to any literary sites and are out of practice as far as recording the occasion goes. We made up for it with lots of pictures at the capitol, which building is subtantially larger than the other state houses I am primarily familiar with, those in Annapolis and Concord. The one in Boston actually looks rather huge too, but I never gone inside it.

2. Dome of the State House, Hartford. We also went to Mark Twain's house while we were in town, but that was evidently so much fun that we forgot to take pictures--it has been a long time since we have been to any literary sites and are out of practice as far as recording the occasion goes. We made up for it with lots of pictures at the capitol, which building is subtantially larger than the other state houses I am primarily familiar with, those in Annapolis and Concord. The one in Boston actually looks rather huge too, but I never gone inside it.

3. Monument to Nathan Hale, The Official State Hero of Connecticut. I made the joke elsewhere that while I love the guy as much as anyone else, Nathan Hale is probably the most overrated of the really famous founding parents, even Molly Pitcher reputedly having brought more actual pain to bear on the enemy. Still, the story of the Revolution and the founding of this republic has a satisfying and classical beauty. I was surprised by how many little reminders and commemorations of this period are to be found in Connecticut, which one does not ordinarily think of as having been a central state in the struggle. Most of the historical reminders are understated, but after a while there are so many of them that the cumulative effect begins to stir feelings of pride and second hand strength in such as are susceptible to them.

3. Monument to Nathan Hale, The Official State Hero of Connecticut. I made the joke elsewhere that while I love the guy as much as anyone else, Nathan Hale is probably the most overrated of the really famous founding parents, even Molly Pitcher reputedly having brought more actual pain to bear on the enemy. Still, the story of the Revolution and the founding of this republic has a satisfying and classical beauty. I was surprised by how many little reminders and commemorations of this period are to be found in Connecticut, which one does not ordinarily think of as having been a central state in the struggle. Most of the historical reminders are understated, but after a while there are so many of them that the cumulative effect begins to stir feelings of pride and second hand strength in such as are susceptible to them.

4. Son #3 Rolling Around on the Grass Outside the State House. While largely devoid of people and activity, the setup of the area around the state house in Hartford looks a lot like a mini-Boston. There is a large park like the Common, maybe 1/4 to 1/2 as large, gathered around one side of it, with a carousel and paved walkways and I believe a place for skating, and many of the streets right off of this park had the same Boston feel of narrowness and a mixture of dignity, age and modern economic necessity emanating from them, including at least one major hotel. As I say though, there were not many people around, I saw mostly intense 20 and 30 something professional types, doubtless employed either in the government or the insurance industry working out (running) in the park. They did not look, as people running sometimes do in Boston, as if they resided anywhere nearby.

4. Son #3 Rolling Around on the Grass Outside the State House. While largely devoid of people and activity, the setup of the area around the state house in Hartford looks a lot like a mini-Boston. There is a large park like the Common, maybe 1/4 to 1/2 as large, gathered around one side of it, with a carousel and paved walkways and I believe a place for skating, and many of the streets right off of this park had the same Boston feel of narrowness and a mixture of dignity, age and modern economic necessity emanating from them, including at least one major hotel. As I say though, there were not many people around, I saw mostly intense 20 and 30 something professional types, doubtless employed either in the government or the insurance industry working out (running) in the park. They did not look, as people running sometimes do in Boston, as if they resided anywhere nearby.

5. Under the Portico Outside the Main Entrance. As I mentioned in a previous post a few weeks ago, Hartford does not have a positive reputation as a city. The demographics are extremely un-New England like, being 41% Hispanic, mainly Puerto Rican, 38% black and just 18% non-Hispanic white. My guess would be that the suburbs around it would be almost all-white: just checking a couple of well-known places, Berlin, where my hotel was, is 97% white, Middletown is 80% white and West Hartford, where the median family income is $98,000 (in the city of Hartford it's $27,000), is 86% white. While Hartford city has demographics more akin to cities in New Jersey or elsewhere in the mid-atlantic, the layout of the streets, housing stock, style of restaurants, bars and other businesses, recognizable chains and of course the vegetation are still predominantly of a New England character. The parts of it that I saw anyway do not look like a place where %30 of the population lives in poverty. It looks tough and a little run down like a lot of the older cities in New England, but compared to poor neighborhoods in the south or the mid-atlantic it looks somewhat livable, and not terribly menacing. The crime statistics that I am finding don't look all that bad, but crime is down almost everywhere from what it was when I was a teenager and in my early 20s, when the murder rate was, looking back at it now, almost unbelievable. I guess the point is, my impression of Hartford is that it's OK, and seeing as I pass through it all the time, maybe I'll stop in again. The Wadsworth Atheneum, their art museum, is apparently a serious place, and there are several other above average touristic attractions there.

5. Under the Portico Outside the Main Entrance. As I mentioned in a previous post a few weeks ago, Hartford does not have a positive reputation as a city. The demographics are extremely un-New England like, being 41% Hispanic, mainly Puerto Rican, 38% black and just 18% non-Hispanic white. My guess would be that the suburbs around it would be almost all-white: just checking a couple of well-known places, Berlin, where my hotel was, is 97% white, Middletown is 80% white and West Hartford, where the median family income is $98,000 (in the city of Hartford it's $27,000), is 86% white. While Hartford city has demographics more akin to cities in New Jersey or elsewhere in the mid-atlantic, the layout of the streets, housing stock, style of restaurants, bars and other businesses, recognizable chains and of course the vegetation are still predominantly of a New England character. The parts of it that I saw anyway do not look like a place where %30 of the population lives in poverty. It looks tough and a little run down like a lot of the older cities in New England, but compared to poor neighborhoods in the south or the mid-atlantic it looks somewhat livable, and not terribly menacing. The crime statistics that I am finding don't look all that bad, but crime is down almost everywhere from what it was when I was a teenager and in my early 20s, when the murder rate was, looking back at it now, almost unbelievable. I guess the point is, my impression of Hartford is that it's OK, and seeing as I pass through it all the time, maybe I'll stop in again. The Wadsworth Atheneum, their art museum, is apparently a serious place, and there are several other above average touristic attractions there.

6. This is Back at Devil's Hopyard. The hiking trails began at the foot of this bridge (on the left). We had our swim first in the pool by the waterfall.

6. This is Back at Devil's Hopyard. The hiking trails began at the foot of this bridge (on the left). We had our swim first in the pool by the waterfall.

7. In the Room at the Best Western in Berlin, CT. I liked our hotel, but one thing I find objectionable about the mid-market chains is that they almost all seem to put too much chlorine in their swimming pools. And yes, breakfast could be a little more dynamic, but I suppose we are lucky we get anything at all.

7. In the Room at the Best Western in Berlin, CT. I liked our hotel, but one thing I find objectionable about the mid-market chains is that they almost all seem to put too much chlorine in their swimming pools. And yes, breakfast could be a little more dynamic, but I suppose we are lucky we get anything at all.

I have been driving across Connecticut 8-10 times a year for most of the last two decades without ever stopping for much more than the occasional hour, so when I had a short four day vacation coming to me in August I decided to go down there for a couple of days as a change from routine. We stayed at a hotel on the Berlin Turnpike in Berlin, about 10 miles south of Hartford, and close to the front line where "New England" in the cultural sense comes to an end and the "New York" homeland, which encroaches a little farther into Connecticut every few years, begins to be predominate. My sense was that we were still pretty squarely on the New England side, though in the way that Alsace is decidedly a part of France while having much more in common with Germany than for example the Loire Valley.

1. Scenic Vista, Devil's Hopyard State Park, East Haddam. This was another recommendation from my 1966 (which I sometime mistakenly refer to as my 1962) encyclopedia, and it was a modest but pleasant site, some mild hiking and a waterfall, as well as a campground. I thought this view had an especially colonial, or maybe an infancy-of-the-republic look about it. Though this is the Connecticut River Valley--itself one of the most idyllic stretches of land I am familiar with--it calls to my mind the spirits of Washington Irving and some of the painters of the Hudson River School.

1. Scenic Vista, Devil's Hopyard State Park, East Haddam. This was another recommendation from my 1966 (which I sometime mistakenly refer to as my 1962) encyclopedia, and it was a modest but pleasant site, some mild hiking and a waterfall, as well as a campground. I thought this view had an especially colonial, or maybe an infancy-of-the-republic look about it. Though this is the Connecticut River Valley--itself one of the most idyllic stretches of land I am familiar with--it calls to my mind the spirits of Washington Irving and some of the painters of the Hudson River School.The affluent town of East Haddam with its antique but still functioning riverside opera house, remains safely within the boundaries of New England. The area around it for a good 15-20 miles in every direction was surprisingly rural, twisting two lane roads, no regular (i.e., non-boutique) hotels, few restaurants. I had originally planned to stay nearer to the park, but the closest hotels were a half an hour away, and these appeared to be or belonged to chains which in our advancing age we consider to be substandard; so we ended up staying closer to Hartford on a busy and somewhat built up though not suffocating stretch of state/U.S. highway where we were able to eat and shop for supplies and of which I grew rather fond by the end of three days.

2. Dome of the State House, Hartford. We also went to Mark Twain's house while we were in town, but that was evidently so much fun that we forgot to take pictures--it has been a long time since we have been to any literary sites and are out of practice as far as recording the occasion goes. We made up for it with lots of pictures at the capitol, which building is subtantially larger than the other state houses I am primarily familiar with, those in Annapolis and Concord. The one in Boston actually looks rather huge too, but I never gone inside it.

2. Dome of the State House, Hartford. We also went to Mark Twain's house while we were in town, but that was evidently so much fun that we forgot to take pictures--it has been a long time since we have been to any literary sites and are out of practice as far as recording the occasion goes. We made up for it with lots of pictures at the capitol, which building is subtantially larger than the other state houses I am primarily familiar with, those in Annapolis and Concord. The one in Boston actually looks rather huge too, but I never gone inside it. 3. Monument to Nathan Hale, The Official State Hero of Connecticut. I made the joke elsewhere that while I love the guy as much as anyone else, Nathan Hale is probably the most overrated of the really famous founding parents, even Molly Pitcher reputedly having brought more actual pain to bear on the enemy. Still, the story of the Revolution and the founding of this republic has a satisfying and classical beauty. I was surprised by how many little reminders and commemorations of this period are to be found in Connecticut, which one does not ordinarily think of as having been a central state in the struggle. Most of the historical reminders are understated, but after a while there are so many of them that the cumulative effect begins to stir feelings of pride and second hand strength in such as are susceptible to them.

3. Monument to Nathan Hale, The Official State Hero of Connecticut. I made the joke elsewhere that while I love the guy as much as anyone else, Nathan Hale is probably the most overrated of the really famous founding parents, even Molly Pitcher reputedly having brought more actual pain to bear on the enemy. Still, the story of the Revolution and the founding of this republic has a satisfying and classical beauty. I was surprised by how many little reminders and commemorations of this period are to be found in Connecticut, which one does not ordinarily think of as having been a central state in the struggle. Most of the historical reminders are understated, but after a while there are so many of them that the cumulative effect begins to stir feelings of pride and second hand strength in such as are susceptible to them. 4. Son #3 Rolling Around on the Grass Outside the State House. While largely devoid of people and activity, the setup of the area around the state house in Hartford looks a lot like a mini-Boston. There is a large park like the Common, maybe 1/4 to 1/2 as large, gathered around one side of it, with a carousel and paved walkways and I believe a place for skating, and many of the streets right off of this park had the same Boston feel of narrowness and a mixture of dignity, age and modern economic necessity emanating from them, including at least one major hotel. As I say though, there were not many people around, I saw mostly intense 20 and 30 something professional types, doubtless employed either in the government or the insurance industry working out (running) in the park. They did not look, as people running sometimes do in Boston, as if they resided anywhere nearby.

4. Son #3 Rolling Around on the Grass Outside the State House. While largely devoid of people and activity, the setup of the area around the state house in Hartford looks a lot like a mini-Boston. There is a large park like the Common, maybe 1/4 to 1/2 as large, gathered around one side of it, with a carousel and paved walkways and I believe a place for skating, and many of the streets right off of this park had the same Boston feel of narrowness and a mixture of dignity, age and modern economic necessity emanating from them, including at least one major hotel. As I say though, there were not many people around, I saw mostly intense 20 and 30 something professional types, doubtless employed either in the government or the insurance industry working out (running) in the park. They did not look, as people running sometimes do in Boston, as if they resided anywhere nearby. 5. Under the Portico Outside the Main Entrance. As I mentioned in a previous post a few weeks ago, Hartford does not have a positive reputation as a city. The demographics are extremely un-New England like, being 41% Hispanic, mainly Puerto Rican, 38% black and just 18% non-Hispanic white. My guess would be that the suburbs around it would be almost all-white: just checking a couple of well-known places, Berlin, where my hotel was, is 97% white, Middletown is 80% white and West Hartford, where the median family income is $98,000 (in the city of Hartford it's $27,000), is 86% white. While Hartford city has demographics more akin to cities in New Jersey or elsewhere in the mid-atlantic, the layout of the streets, housing stock, style of restaurants, bars and other businesses, recognizable chains and of course the vegetation are still predominantly of a New England character. The parts of it that I saw anyway do not look like a place where %30 of the population lives in poverty. It looks tough and a little run down like a lot of the older cities in New England, but compared to poor neighborhoods in the south or the mid-atlantic it looks somewhat livable, and not terribly menacing. The crime statistics that I am finding don't look all that bad, but crime is down almost everywhere from what it was when I was a teenager and in my early 20s, when the murder rate was, looking back at it now, almost unbelievable. I guess the point is, my impression of Hartford is that it's OK, and seeing as I pass through it all the time, maybe I'll stop in again. The Wadsworth Atheneum, their art museum, is apparently a serious place, and there are several other above average touristic attractions there.

5. Under the Portico Outside the Main Entrance. As I mentioned in a previous post a few weeks ago, Hartford does not have a positive reputation as a city. The demographics are extremely un-New England like, being 41% Hispanic, mainly Puerto Rican, 38% black and just 18% non-Hispanic white. My guess would be that the suburbs around it would be almost all-white: just checking a couple of well-known places, Berlin, where my hotel was, is 97% white, Middletown is 80% white and West Hartford, where the median family income is $98,000 (in the city of Hartford it's $27,000), is 86% white. While Hartford city has demographics more akin to cities in New Jersey or elsewhere in the mid-atlantic, the layout of the streets, housing stock, style of restaurants, bars and other businesses, recognizable chains and of course the vegetation are still predominantly of a New England character. The parts of it that I saw anyway do not look like a place where %30 of the population lives in poverty. It looks tough and a little run down like a lot of the older cities in New England, but compared to poor neighborhoods in the south or the mid-atlantic it looks somewhat livable, and not terribly menacing. The crime statistics that I am finding don't look all that bad, but crime is down almost everywhere from what it was when I was a teenager and in my early 20s, when the murder rate was, looking back at it now, almost unbelievable. I guess the point is, my impression of Hartford is that it's OK, and seeing as I pass through it all the time, maybe I'll stop in again. The Wadsworth Atheneum, their art museum, is apparently a serious place, and there are several other above average touristic attractions there. 6. This is Back at Devil's Hopyard. The hiking trails began at the foot of this bridge (on the left). We had our swim first in the pool by the waterfall.

6. This is Back at Devil's Hopyard. The hiking trails began at the foot of this bridge (on the left). We had our swim first in the pool by the waterfall. 7. In the Room at the Best Western in Berlin, CT. I liked our hotel, but one thing I find objectionable about the mid-market chains is that they almost all seem to put too much chlorine in their swimming pools. And yes, breakfast could be a little more dynamic, but I suppose we are lucky we get anything at all.

7. In the Room at the Best Western in Berlin, CT. I liked our hotel, but one thing I find objectionable about the mid-market chains is that they almost all seem to put too much chlorine in their swimming pools. And yes, breakfast could be a little more dynamic, but I suppose we are lucky we get anything at all. Monday, September 13, 2010

Deliverance Part 2

I seemed to think that the prose poem type style employed in this book was big at the time. What else could I have been thinking of? John Gardner's Grendel? Margaret Drabble's The Waterfall? The works of Donald Barthelme? It does seem to be characteristic of the kind of writing that was praised in university writing programs of the period, the better examples of which I have begun to find more tolerable in recent years.

The woods in the north are not as scary as what we find in this book, though judging by my trip to the Blue Ridge and Smokies this summer, even much of Appalachia has largely been tamed and brought within the pale of semi-respectable civilization.

Page 28, some married, mature adult sex talk (My initial response was 'yucky'). "I knelt and entered her, and her buttocks rose and fell. 'Oh,' she said, 'oh yes.'" Hey, I'm sure he did. Good for him.

On page 37, a reminiscence of vomiting after the office Christmas party. One thing I am truly jealous of the 60s for is that it had awesome Christmas parties, both at the office and in private homes, the like of which seem unlikely to return before I am too far gone into my dotage to enjoy them any longer.

These guys really are suburban if they can't recognize different kinds of trees, never see deer, and so on. Of course at this time, and throughout my earlier childhood certainly, one did not see nearly as many animals out by the highway as one does today. Deer especially, though one occasionally saw them in the country, but turkeys, skunks, foxes, porcupines, I don't recall ever seeing at all until I was in my twenties at least, and now they seem to be quite numerous even in well-populated areas.

These guys really are suburban if they can't recognize different kinds of trees, never see deer, and so on. Of course at this time, and throughout my earlier childhood certainly, one did not see nearly as many animals out by the highway as one does today. Deer especially, though one occasionally saw them in the country, but turkeys, skunks, foxes, porcupines, I don't recall ever seeing at all until I was in my twenties at least, and now they seem to be quite numerous even in well-populated areas.

P. 69: "He went down the other side as I came up, feeling dirt on my hands for the first time in years." This has to be an exaggeration. His wife never wanted him to dig or pull up any roots or trees in the backyard?

On page 76 there is a discussion of plastic, how it does not decompose and go back to its elements. Plastic is a good example of a evil that people at the time when it began its ascendence recognized and denounced almost at once, and of which everyone was more or less powerless to stop the proliferation anyway. Was much in the collective thought of the era.

What is the word for what this story is trying to be? A fable? It is trying to do the kind of thing I really like, which is to write about something quite implausible in such a way that it seems, or becomes for the time anyway, as believable and 'real' as anything else one's mind has encountered, but I don't think it quite makes it.

The kind of male-bonding that is a big part of this book is not really done much anymore, at least among urban/overcivilized types, of which group I am kind of a member. Personally I would prefer the Mr Chips style male bonding holiday, where one discusses theories of art or geological discoveries with a mental and social equal rather than carrying weapons and fighting with either wild animals or savage men, though it looks like neither is very likely to happen anytime soon.

The kind of male-bonding that is a big part of this book is not really done much anymore, at least among urban/overcivilized types, of which group I am kind of a member. Personally I would prefer the Mr Chips style male bonding holiday, where one discusses theories of art or geological discoveries with a mental and social equal rather than carrying weapons and fighting with either wild animals or savage men, though it looks like neither is very likely to happen anytime soon.

The theme of the book, I venture, is that we should always assume trouble. It is the normal condition of life. We have let our guard down in comfortable modern life--life is supposed to be fairly horrible a good deal of the time, and we try to skirt that at our own peril.

This is definitely a pre-cell phone adventure.

The narrator, on the unfortunate friend who got raped, after the fact: "None of this was his fault, but he felt tainted to me. I remembered how he had looked over the log, how willing to let anything be done to him, and how high his voice was when he screamed." Yes Abby, we're a long way from Wordsworth now.

Is the book optimistic about human capability even when the proper manly spirit and knowledge have atrophied? I think it is on the fence.

Is the book optimistic about human capability even when the proper manly spirit and knowledge have atrophied? I think it is on the fence.

I wa surprised at the brevity of the famous scene. The rest of the plot--about 150 pages--seems dictated by necessities that are predictable based on the length of the book.

Beholding (as opposed to seeing) the river is presented as having some kind of relevance to life. Nature in this book is always presented as being rather alien to the most refined human qualities. On page 171 alone it is described as "blank", "mindless", "icy" and "uncomprehending". It offers no guidance to a man. Compare this with some lines from John Denham on the Thames River, written in 1655:

"O could I flow like thee, and make thy stream

My great example, as it is my theme!

Though deep, yet clear; though gentle, yet not dull;

Strong without rage, without o'erflowing full."

This is culturally, I think, a more serious and useful way of engaging with nature.

I seemed to think that the prose poem type style employed in this book was big at the time. What else could I have been thinking of? John Gardner's Grendel? Margaret Drabble's The Waterfall? The works of Donald Barthelme? It does seem to be characteristic of the kind of writing that was praised in university writing programs of the period, the better examples of which I have begun to find more tolerable in recent years.

The woods in the north are not as scary as what we find in this book, though judging by my trip to the Blue Ridge and Smokies this summer, even much of Appalachia has largely been tamed and brought within the pale of semi-respectable civilization.

Page 28, some married, mature adult sex talk (My initial response was 'yucky'). "I knelt and entered her, and her buttocks rose and fell. 'Oh,' she said, 'oh yes.'" Hey, I'm sure he did. Good for him.

On page 37, a reminiscence of vomiting after the office Christmas party. One thing I am truly jealous of the 60s for is that it had awesome Christmas parties, both at the office and in private homes, the like of which seem unlikely to return before I am too far gone into my dotage to enjoy them any longer.

These guys really are suburban if they can't recognize different kinds of trees, never see deer, and so on. Of course at this time, and throughout my earlier childhood certainly, one did not see nearly as many animals out by the highway as one does today. Deer especially, though one occasionally saw them in the country, but turkeys, skunks, foxes, porcupines, I don't recall ever seeing at all until I was in my twenties at least, and now they seem to be quite numerous even in well-populated areas.

These guys really are suburban if they can't recognize different kinds of trees, never see deer, and so on. Of course at this time, and throughout my earlier childhood certainly, one did not see nearly as many animals out by the highway as one does today. Deer especially, though one occasionally saw them in the country, but turkeys, skunks, foxes, porcupines, I don't recall ever seeing at all until I was in my twenties at least, and now they seem to be quite numerous even in well-populated areas.P. 69: "He went down the other side as I came up, feeling dirt on my hands for the first time in years." This has to be an exaggeration. His wife never wanted him to dig or pull up any roots or trees in the backyard?