The emphasis on our (postmodern man's) being out of touch with our bodies, while it seems to be a ubiquitous theme throughout the culture, is more obsessively pursued here than it is in most discourses which take up the subject. I generally think this problem is overstated; that is, it would be my position that our intellects and spirits, relation to language and art and reason and so on, being equally out of sync, and all of these estrangements being problems and deficiencies of the mind above all, that a hyper-increased physicality in itself is unlikely to restore one to a more interesting or complete sense of self.

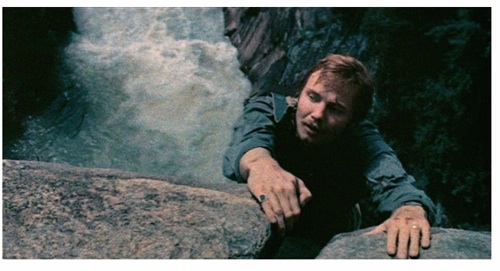

The emphasis on our (postmodern man's) being out of touch with our bodies, while it seems to be a ubiquitous theme throughout the culture, is more obsessively pursued here than it is in most discourses which take up the subject. I generally think this problem is overstated; that is, it would be my position that our intellects and spirits, relation to language and art and reason and so on, being equally out of sync, and all of these estrangements being problems and deficiencies of the mind above all, that a hyper-increased physicality in itself is unlikely to restore one to a more interesting or complete sense of self.p.184: "I was aided by a totally different sense of touch than I had ever had, and it occurred to me that I must have developed it on the cliff." The book has a great belief in unrealized abilities that the circumstances of contemporary life have dulled in us, but that necessity, or adversity, could awaken if we found or put ourselves in a position to experience it. I do believe that when literal survival is at stake, such as in war, that something of this hyperacute awareness and sensibility does instinctively arise, and perhaps these realizations insinuate themselves permanently into consciousness. It is not my impression however that they contribute substantially to a permanent strength of mind if the foundation for such a mind be not already in place.

I interpret the story as supposed to be ultimately uplifting when the main character, Gentry, discovers his power to kill. I was taken along for some ways by this idea, though I was concerned about my health and mental fitness. Among the book's other main lessons is that somebody has to be in charge, has to take charge, and of course in the state of nature or even sometimes in advanced stages of civilization that often involves having to be willing to kill someone.

"Cornholed". There's a nice word. "...a man who had held a gun on it while another one cornholed him..."

The primal energy of the water was remarked upon numerous times. The means writers make of and the importance they attach to water symbolism--and almost all do--is the intellectual equivalent of Gentry's heightened sense of touch when scrambling for his life up the rocks. It ought to be second nature to a properly developed and highly functioning intellect.

The book on the whole, believe it or not, is very understated (quiet, modest, etc).

I wonder how these guys would have handled 3rd world immigration. Probably not well.

No comments:

Post a Comment