hand precognition and genius people crazy said stardom

I wanted to make a few remarks on the recent retirement of Mariano Rivera. I have been planning to do this all season, not because he was an iconic and unusually beloved player whose departure undoubtedly marks the close of a significant era in New York City sports history, which various eras parallel those in the city's social history with surprising closeness, but because he was the last remaining active player in any of the three big professional team sports who was older than I am. I have not gotten around yet to watching the dramatic scene from his final game when he broke down in tears after facing his last batter, probably because I heard and read too much about it in the days after it happened from people with whom I don't feel any bond. Still, it is a milestone that my generation has now passed from the competitive professional sporting scene entirely. Even if Brett Favre wants to come back again, I don't think they will let him at this point. Rivera had become an exceptionally piquant player in recent years due to the circumstance that his mere presence on the field, and even around town in some instances, had become comforting and even uplifting to New York fans, many of whom of course are legitimately sophisticated people. When he made his first appearance in a game at the beginning of this season after having missed most of last year due to tearing up his knee, numerous of my 40-something New York area friends expressed a mild but palpable excitement and joy that is rarely felt by people our age. Even though he is a link to when we were younger, and the city, while already in transition to its present state, still had a different personality and feel about than it has now, this was not, I think, all about nostalgia and the lost Eden, for many of my contemporaries adapted well to the new world and the new New York--indeed, they may be said, by their agility in and embrace of these, to have grown up along with them and contributed in no insignificant way to their development. Still, while the responses of middle-aged fans to Rivera's last year were tributes to an ongoing sense of excellence and stability and sense of self that he projected, it is hard not to feel that an era is coming to an end, and not merely in baseball.

Eras in New York sports history track pretty squarely with the prevailing cultural and socio-economic zeitgeist. Obviously one could make the same argument with regard to Broadway shows, or restaurants, or toy stores, or anything else. Sports come at things from a somewhat different angle, and it is not always obvious how the era of sweatshops and teeming tenements and Tin Pan Alley connects with the career of Christy Mathewson, other than that the life trajectories of these disparate careers and phenomena coincide rather wonderfully.

1840s--Invention of baseball, or at least the first widespread evidence of its being a popular recreation. Working men would ferry from the city to Brooklyn and Hoboken, much of both of which cities at that time was still farmland.

I'm skipping ahead a few decades, as I don't have any sense of the New York sports scene from 1850-1880.

1883-1892--The Buck Ewing era. The early New York Giants had an outstanding team in this era, with multiple Hall of Famers, culminating in back-to-back pennants in 1888 & '89. The team relocated from Troy (N.Y.) to the original Polo Grounds in 1883. Ewing continued to receive votes in media polls for the greatest player of all time into the 1940s, after which presumably everyone who had any memory of him had passed on. This was the era when fighting, drinking, gambling, throwing bottles at the umpires, etc, reached its zenith, and a lady would no sooner go to a ballgame than she would to a cockfight. It sounds reminiscent of the 1970s.

1893-1899--The personality of the remainder of the sporting 1890s in New York is unclear to me. Baltimore and Boston had the most famous teams in this period (though Brooklyn had some good years). When I was a child, the 1890s were still (sort of) dimly remembered as "gay"--images still come to mind of mustachioed men in bowler hats riding unicycles and ladies in white fruffy dresses with matching parasols seated in the carriage of an early motorcar singing "In the Good Old Summer-Time" as they puttered under the elm-tree and picket fence-lined avenue--but in many ways it had a lot of similarities to our own time. Cheating was rampant, not merely in sports but throughout society, enormous fortunes were amassed even though there was a major economic depression in the middle of the decade, immigration was transforming the population, technological and economic forces were rendering millions obsolete and leaving them and their children seemingly behind forever. Yet because the upper middle and wealthy classes lived so charmingly in this period, or came to be seen as having done so, by the 1950s, 60s, 70s, this image of the decade had become the predominant one in the popular memory.

1900-1915--The Christy Mathewson/John McGraw era. The years when the Giants ruled New York--indeed, as Laughing Larry Doyle put it circa 1911, "It's great to be young and a Giant." They were a fascinating team. McGraw was famous for being a short-tempered Irish bully, but he loved the Bucknell -educated and gracious Mathewson like a son and among his players there were as many who could be said to be almost gentlemen, especially when compared with the era of the 1890s when he himself had played--Rube Marquard, whose immigrant parents had wanted him to be a doctor and despaired at his becoming a ballplayer, Chief Meyers, Fred Snodgrass, the eccentric Charles Victory Faust, a non-player who persuaded McGraw that he had had received a prophecy that the Giants would win the pennant if they put him on the team (they did). McGraw would last as the manager until 1932, and even enjoy a run of success with four straight pennants and 2 more championships from 1921-24, but by that time he was a decided second banana in town.

1916-1919--interregnum--like Western civilization, the original Giant dynasty suddenly fell apart in August of 1914. McGraw did manage to lead a fairly nondescript team to a pennant in 1917, where they lost the World Series, but overall this was a dark few years of baseball history, plagued by gambling and ferocious battles over money, as well as the last years of the 'dead-ball' era, which like the last years of any era appears in retrospect to have been tired and waiting for the next big development to come along, even though at the time no one had any sense of this happening.

1920-1934--Babe Ruth era. The Babe was obviously one of the main men of the roaring 20s in any field. His age overlaps into the first half of the Depression, though his departure does coincide more or less with the ascendance of Roosevelt and the New Deal and the more sober mayorality of Laguardia--almost as if nobody could fully realize until the Babe faded that the good old days were really gone and politics and the temperament of the city could move on accordingly

1933-1937--New Deal Interlude, Gehrig/Hubbell/Ott micro-era. Giants briefly resurgent with 3 pennants and 1 championship, Yankees in transition '33-'35.

1936-1951--DiMaggio era, core from 1937-47, covering the World's Fair, consolidation of New Deal. World War II and the flush of the immediate aftermath before the big postwar developments (television/suburbanization) roared into full throttle

1947-1955--Another overlapping period--Jackie Robinson/Boys of Summer/Young Willie Mays/Yogi Berra era. Last notable thrusts, ever diminishing through this crucial period, of the old New York of the 1900-45 period.

1951-1968--Mickey Mantle era, core from 1956-64. Departure of baseball Dodgers & Giants to west coast in 1958 taken by many at time as symbolic of cultural shift to California. Also features the glamorous New York Giant football team in that era, with Frank Gifford, Rosey Grier, Sam Huff, Kyle Rote, Y.A. Tittle, among the first N.F.L. players to achieve widespread crossover fame. After long runs of success the Giants abruptly collapsed in '64 and the Yankees in '65, with neither team to re-emerge as a force for more than a decade. In that same year the city was struck by the famous blackout and the ill-fated Lindsay was elected mayor.

1967-1973--Joe Namath/Tom Seaver/Willis Reed era. The city descends into its infamous epoch of crime, filth & bankruptcy, though in these years it retains a certain charm in sports/movies/popular culture anyway. By the time the Mets drop the World Series in October of '73 even this charm is largely played out.

1974-1975--The Death Wish era.

1976-1981--Bronx Zoo Era. Crime and filth firmly entrenched, believed at time to be permanent and unresolvable. Lots of decadence--disco, cocaine, rampant sex to the extent of, in many cases, physical debilitation and even death. To my unending surprise this era has in recent years become somewhat celebrated (by those in the know) as a great one in the annals of the city, with an intellectual ferment and sexual energy and flavor to daily life that today's sanitized corporate city is lacking. I think once the more self-aggrandizing baby boomer and stridently anti-social generation x-types who are pushing this narrative pass on, it will be difficult for most people to honestly feel this to be the case. This is the city I encountered on my first visit as an 8 year old in 1978, already well immersed from books and so in an image of the city that dated from the pre-1960 period at least. It was still exciting to be there, but my impression was that it was obviously pretty crummy compared to what it used to be and that I had missed the beautiful time.

1982-1990--The Mattingly/Gooden/Mets/Bill Parcells/Chris Mullin era. I'm not sure what the defining characteristic of this period was. Old school rap music? When I see a movie made during these years I think, oh yes, that's New York the way I usually think of it as being, even now.

1991-1994--Another transition period. Patrick Ewing era?

1995-2013--Rivera/Jeter, et al era--coincides with Giuliani/Bloomberg mayorships, crime decline, techno-city and new gilded age. Whatever has been lost in this new age, whenever I go there now I can never get over how clean it is. It seemed impossible in the 1970s and 80s.

My computer is running out of juice, or something, and I want to finish off this post, but as I have been watching the baseball playoffs, and seeing the Detroit Tigers lose several games because they had to take out their star pitcher in the 7th inning due to his pitch count getting to 110, I was reminded of how much I hate pitch counts. I had seen that somebody had put up a link to the full telecast of Game 7 of the 1965 World Series, when Sandy Koufax threw a three hit shutout on two days rest in a 2-0 victory. I have long been curious about what pitch counts were like in the 60s and beyond, when pitchers threw way more innings and complete games than they do today (Koufax in '65 for example pitched 323 and 27 in these categories in the regular series, before making three starts and throwing 2 more shutouts in the World Series). I thought it possible that pitchers might have been able to breeze through games in 110 pitches or less, seeing as lineups in the 60s were loaded with 150-pound middle infielders who hit .215 with no power, overweight guys with glasses who hit .230 and popped a home run once a week or so, pitchers still batted in both leagues, and consciously trying to build up the opposing pitcher's pitch count to get him out of the game was not employed as a particular strategy, because the pitcher wouldn't be taken out of the game unless he was getting hit harder than his relief would likely be. In short, I decided to track Koufax's pitch count for Game 7. To my surprise it was pretty high, given that he only gave up three hits and three walks and the Twins never came really close to scoring. He threw 132 pitches (on two days rest, remember), 86 for strikes, for the record. He threw 26 in the first inning alone, when he walked two hitters, but after that he was between 10 and 19 for every other inning. Breaking it down further, from innings 1-3 he threw 50 pitches, 39 in innings 4-6, and 43 in innings 7-9. His 100th pitch came with two outs in the 7th. At the end of seven innings he had thrown 103 pitches, at the end of eight 116. There was someone warming in the bullpen in the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 8th innings (shown after pitch 109), which surprised me, though it indicates that there was some slight concern about Koufax's stamina, and manager Alston made a visit to the mound in the fifth. Koufax gave up a single on pitch 124, with one out in the 9th in a 2-0 game. Even in the (doubtful, near miraculous) event that a starter would still be in at that point in today's baseball, it is impossible to imagine a manager daring to leave him in the game at that point, whoever he was. There were also three check swings that were called balls where the batter so blatantly went around that I was embarrassed for the umpires. These were all on what would have been third strikes, and probably added 5-7 pitches to Koufax's total. The Twins sent up a left-handed pinch hitter to face Sandy Koufax trailing 2-0 in the 8th inning of Game 7 of the World Series. I think those are all the notes I took on the game.

Maybe I will do this on some other historic games. I am curious about it. However, it just demonstrates how this insidious number of the pitch count has totally taken over the way people like me experience baseball games. The whole drama and mental focus of the middle innings now is how many outs can the starter get through before he hits his number and has to leave the game. There is no chance of his having to gut out a nine inning--let along extra-inning victory, and will likely be afforded the opportunity to finish nine innings once or twice a year, and then only if he encounters no trouble--literally nothing goes even slightly wrong--over the last two innings. I dislike this. However, I have to end the post now or it could be another week before I finish it...

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Got To Keep Up With the Movie Posts

I have lots of great essays on general and pertinent topics coming.

The Journey of Natty Gann (1985)

Disney movie, not really for little children so much as for the 10-14 range I would think, that one of my ratings guides (my favorite one, actually) really liked. I don't think they make this kind of movie much anymore. The modern child would doubtless find its pace and method of storytelling hopelessly old-fashioned and ponderous. Not my children perhaps, or at least some of them, but we seem to be well out of the main currents of contemporary life. I already feel my sons' pain when they will arrive at college and be surrounded by boys who have long had the text message booty call (or whatever its 2020s equivalent will be) down cold; because they probably won't. I didn't like the movie quite that much, though I'm not going to rip it either. It is set in the 30s, a time period which often works well in cinematic renderings, and is probably popular for that reason. Comparatively speaking, movies from the 20s are much rarer, and usually feel off besides; and the 1910s are essentially a decade forgotten by everyone at this point, in part because nobody has a good feel, or much interest, in how to make visually compelling movies about them. But filmmakers seem to have some sense of the aesthetic of the 30s, what they felt like visually if nothing else, that is more accurate than that which they have for other periods.

The star of the movie was the great Meredith Salenger, who is two months younger than I am. Who didn't

Reminder of What the 80s Could Have Been Like (if it had only been given to one to be a winner)

I have assumed in past posts (Vanessa Paradis, Jennifer Connelly) the privilege of being allowed to express my teen-aged thoughts about teen-aged girls who were teenagers at the same time I was. Is it not more wistful in that sense than perverse, to recall that lost but in retrospect beautiful summer of 1985, when Meredith and I were both 15, and I was walking up the Easton Road or across some parched empty ball field on a 93 degree day, and she was out there, in Hollywood hanging out with the Corey Feldmans of the world, our paths decidedly not doomed to cross...I have always liked the name Meredith, since about 1985 in fact, enough that usually the mere hint that one bearing that name might be in the vicinity has always had the effect of piquing my consciousness and arousing some heat to flow into the old joints in anticipation of pleasurable experience. The name calls to mind the girl one knew at summer camp (I never went to summer camp), standing on the dock, framed by the encompassing silhouette made by countless and endless pine trees, her wet shoulder length hair and field hockey player's taut calves and arms glistening in the half moon, and you soon to know to partake of the pleasure contained in this for the first time...For those of us who never got to be young in this way, there is a kind of therapy in pretending we once were.

I once knew a bartender named Meredith who was kind of a loudmouthed party girl, but I liked her personality. She had a slight belly, but she had beautiful arms, and beautiful teeth, both of which stood out especially, as well as blue eyes and shoulder length black hair which had, or which she had given, the aspect of being animated. She had no use for me at all, but how could she? I have no personality, have nothing to say that will interest them, to 999 out of every 1,000 women I encounter.

I could look at pictures of Meredith Salenger, if not quite all day, for a while. I had forgotten about her. Probably this was for the best.

Meredith Salenger Today.

And Another One. Hey, Why Not?

To Die in Madrid (1963)

This could go on the list of supposedly great movies that are not readily available in this country. I did watch it on the internet, however I could not find any uploads (?) of it with English subtitles. It is in French, and while I can understand more French than I can any other language, I don't understand it well enough to really follow the narration in its finer points. The movie is a documentary about the Spanish Civil War. Whether all of the footage was historical or if there were some parts (the non-battle, non-mass crowds under wartime condition parts obviously), mainly of traditional or pastoral settings, that were filmed contemporaneously by the (a?) director. The Spanish Civil War of course has always spoken to intellectuals and artists. Apart from the most superficial facts and analyses of it I don't know very much about it, as least not what inspires such deep responses to it by astute and gifted people; though perhaps it is nothing more than the sense of the unique and antiquated beauty of the Spanish country and culture that seems viscerally to contain a depth and nobility that is inaccessible to people living in modern societies. I don't know how much this movie would have taught me, as I got the impression from the narrator's tone of voice, what I could make out of the French, and the types of footage that were emphasized, that the filmmakers were of the strident, highly indignant school and that the view of the war that they were pressing, while it might have explained a great deal, might also have explained nothing useful to me. Nonetheless, the film was strong on this antiquated Spanish beauty and atmosphere--is it a lie, or a distraction from facing very unpleasant facts about a culture (or the several cultures who co-exist to however much of an extent in the territory known as Spain) and the people who make it up? I don't think so, simply because the atmosphere is so seductive and is the main reason many people care so much about the war that took place there in the 1930s. I have very much wanted to go to Spain over the last couple of years, as if doing so would clear my head and restore my lost equilibrium in some way, as if all of the elements that I am missing and which are essential to living a fully human life, or at least a Western idea of a human life, could still be found there.

Witness For the Prosecution (1957)

As I have noted often, courtroom movies are not the kind of thing I usually get excited about. I was a little more open to seeing this one than the run of pictures of this type, because it was directed by Billy Wilder and had Charles Laughton as one of its stars. Wilder is probably in the top five of my all time favorite directors at this point, and while I have not seen a lot of Charles Laughton, I already have the idea that he always delivers. And Laughton does deliver here. He is great, the movie is worth watching for him alone. It is not that Billy Wilder doesn't deliver--the movie is eminently watchable, and makes for good entertainment--it does not exactly feel like a Billy Wilder movie however. This is probably because it is based on an Agatha Christie story and is set in the Inns of Court in London. I have never read any Agatha Christie, but this is the 2nd movie (And Then There Were None was the other) based on one of her stories that I have seen; evidently her trademark was the multiple twist ending. These are clever, but they are not, at this stage of my development, what I am going to remember, or even be particularly interested in, about either of these films. Among the other stars in this movie worth noting are Marlene Dietrich, whom I had never seen before, and who I thought had retired after the 30s. She is about 55 in this and looks quite remarkable. Combined with her German attitude this is at times a genuinely scary combination. Elsa Lanchester, a great beauty in the 30s (Rembrandt) and the wife of Charles Laughton, looks more her age, which is the same as Marlene Dietrich's, in a deliberately somewhat dowdy role here, though it is still evident that she had been a beautiful young woman. Charles Laughton himself was always one of those jowly, enormous-headed, highly competent and well-trained, brandy-drinking, decidedly non-metrosexual British men of the Brideshead generation (what happened to this stock?). Tyrone Power, an American who was a fairly big star for a brief period in the 50s (he died of a heart attack at age 44 the year after this came out) was in this as well. I haven't seen him before; he wasn't very impressive--or at least he seems out of place--when contrasted against all of the other talent here.*

I would give this movie 3 1/2 stars out of five, maybe push it to four on the basis of Laughton's performance alone. Otherwise my prejudice against courtroom movies is too much to overcome for me to truly love it, and the cleverness of the twists at the end after being led so diligently for the better part of two hours to another specific and pat conclusion does not provide enough satisfaction. It is much better to have a sense of myriad possibilities for an ending and anticipate which direction the story will end up taking than to be persuaded throughout that the story and the characters are of such and such a type, only to have the switch at the end that tells you, no, no, it is all completely the opposite of what the entirety of our previous storytelling would have permitted you to believe, which latter I obviously do not like as a technique.

*I have since discovered that Tyrone Power was actually quite a big star in the 1930s and 40s. However he must be largely forgotten today, as I had scarcely heard of him and had never seen him in a movie until this.

Sunday, October 06, 2013

Vivian Grey (1826-7)--Benjamin Disraeli Part 1

basis porch gathering alone 1834 undergraduates

I started this May 6, 2009. I scarcely remember anything about it, except that the title character went to Germany and hung out in several bizarre castles belonging to various of the petty princelings there, and that there was not a plot that was intelligible to me over the last 2/3rds of the book. So I am going to have to rely on my largely illegible notes to see what my impressions of it were.

This is a 393 page Victorian novel written by a 21-year old. It shows in over-elaborate constructions (I presume sentence constructions), and 100-something something, (maybe 100-pound words)?

I could have used a glossary for all the school terms and slang (I have still not really learned to use the internet as a real-time reference while reading, though I will go to it if there is a question that I simply must have the answer to).

Someone's eyes gaze 'in all the vacancy of German listlessness." This was the stereotype for a long time. Of course most people in the West wold have considered the Chinese and the Indians to have been listless as recently as the 1960s. I wonder what happens at certain points of history to kick large groups of people into gear where in the course of a generation they come to be seen as just about the antithesis of listless (and apply the discovery in my own family).

I was musing at one point about Vivian's being a member of the famous family of literary Greys--Dorian, Agnes, et al--I did not check the spelling on these names, and besides bohemian English people are at liberty to spell their names any way they want. This probably tells you something about how scintillating the story was.

It only took to page 57 to find the Minor Character Who is Just Like Me for this book: "Mr Boreall (nice name) was one of those unfortunate men who always take things to the letter."

Goethe was still alive at the time this book was published. For some reason this struck me as remarkable when I considered it at the time.

Party Girls in Warsaw (see below)

It also struck me as remarkable that the author of such a juvenile novel could go on to have the political career that Disraeli had without constantly being attacked about the thoughts he revealed in it. Maybe he was, but it doesn't seem to have hurt him if it did happen.

I also noted on the same page that Disraeli was obviously of the type that has no sympathy for timid hem-hawers, people who don't know their own minds.

It only took as far as page 79 to find the one sentence Anti-me of this book: "Frederick Cleveland was educated at Eton and at Cambridge; and after having proved, both at the school and the University, that he possessed talents of a high order, he had the courage, in order to perfect them, to immure himself for three years in a German University."

B.D. is more of a teller than a shower (as in one who shows, not a fall of water under which one cleans oneself, which is how I was trying to read it before I could decipher "teller").

This is a strange book. Mrs Felix Lorraine is strange. The scene of the midnight meeting evokes the college atmosphere well though, via rustles, shadows, odd silence and the unnatural stillness of objects. This is all one note, and I don't have the slightest idea what I meant by it.

Smart people (really smart people) have so much attitude and easy superiority. It gets to be a bit much for me however.

Of course they have to talk about Byron. His role in the civilizational imagination at this time cannot be overstated. He was a presence that people could not get around. When Byron's admiration of Bolivar is referenced, it is spoken of as if Bolivar's personal greatness is confirmed as much by Byron's opinion of it as by the man's own actions. Frederick Cleveland, already shown to be a superior being himself, said of the poet, "He was indeed a real man; and when I say this, I award him the most splendid character which human nature need aspire to."

Heidelberg is described as 'a place of surpassing loveliness, where all the romantic wildness of German scenery is blended with the soft beauty of the Italian." I haven't been there.

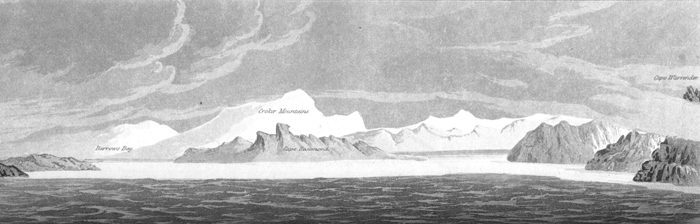

Warsaw is described as a 'Paradise of women' by the Baron Julius von Konigstein. I suspect that it is. The Baron was a great traveler, and claimed that the only places he hadn't seen were "In Europe...the miracles of Prince Hohenlohe. In Asia, everything except the ruins of Babylon; In Africa, I have seen everything but Timbuctoo; and in America, everything except Croker's Mountains." Croker's Mountains were a mirage reported as being seen near Baffin Island in Arctic Canada by a British explorer who was searching for the Northwest Passage, the non-existence of which were demonstrated shortly before this book was written.

I started this May 6, 2009. I scarcely remember anything about it, except that the title character went to Germany and hung out in several bizarre castles belonging to various of the petty princelings there, and that there was not a plot that was intelligible to me over the last 2/3rds of the book. So I am going to have to rely on my largely illegible notes to see what my impressions of it were.

This is a 393 page Victorian novel written by a 21-year old. It shows in over-elaborate constructions (I presume sentence constructions), and 100-something something, (maybe 100-pound words)?

I could have used a glossary for all the school terms and slang (I have still not really learned to use the internet as a real-time reference while reading, though I will go to it if there is a question that I simply must have the answer to).

Someone's eyes gaze 'in all the vacancy of German listlessness." This was the stereotype for a long time. Of course most people in the West wold have considered the Chinese and the Indians to have been listless as recently as the 1960s. I wonder what happens at certain points of history to kick large groups of people into gear where in the course of a generation they come to be seen as just about the antithesis of listless (and apply the discovery in my own family).

I was musing at one point about Vivian's being a member of the famous family of literary Greys--Dorian, Agnes, et al--I did not check the spelling on these names, and besides bohemian English people are at liberty to spell their names any way they want. This probably tells you something about how scintillating the story was.

It only took to page 57 to find the Minor Character Who is Just Like Me for this book: "Mr Boreall (nice name) was one of those unfortunate men who always take things to the letter."

Goethe was still alive at the time this book was published. For some reason this struck me as remarkable when I considered it at the time.

Party Girls in Warsaw (see below)

It also struck me as remarkable that the author of such a juvenile novel could go on to have the political career that Disraeli had without constantly being attacked about the thoughts he revealed in it. Maybe he was, but it doesn't seem to have hurt him if it did happen.

I also noted on the same page that Disraeli was obviously of the type that has no sympathy for timid hem-hawers, people who don't know their own minds.

It only took as far as page 79 to find the one sentence Anti-me of this book: "Frederick Cleveland was educated at Eton and at Cambridge; and after having proved, both at the school and the University, that he possessed talents of a high order, he had the courage, in order to perfect them, to immure himself for three years in a German University."

B.D. is more of a teller than a shower (as in one who shows, not a fall of water under which one cleans oneself, which is how I was trying to read it before I could decipher "teller").

This is a strange book. Mrs Felix Lorraine is strange. The scene of the midnight meeting evokes the college atmosphere well though, via rustles, shadows, odd silence and the unnatural stillness of objects. This is all one note, and I don't have the slightest idea what I meant by it.

Smart people (really smart people) have so much attitude and easy superiority. It gets to be a bit much for me however.

Of course they have to talk about Byron. His role in the civilizational imagination at this time cannot be overstated. He was a presence that people could not get around. When Byron's admiration of Bolivar is referenced, it is spoken of as if Bolivar's personal greatness is confirmed as much by Byron's opinion of it as by the man's own actions. Frederick Cleveland, already shown to be a superior being himself, said of the poet, "He was indeed a real man; and when I say this, I award him the most splendid character which human nature need aspire to."

Heidelberg is described as 'a place of surpassing loveliness, where all the romantic wildness of German scenery is blended with the soft beauty of the Italian." I haven't been there.

Warsaw is described as a 'Paradise of women' by the Baron Julius von Konigstein. I suspect that it is. The Baron was a great traveler, and claimed that the only places he hadn't seen were "In Europe...the miracles of Prince Hohenlohe. In Asia, everything except the ruins of Babylon; In Africa, I have seen everything but Timbuctoo; and in America, everything except Croker's Mountains." Croker's Mountains were a mirage reported as being seen near Baffin Island in Arctic Canada by a British explorer who was searching for the Northwest Passage, the non-existence of which were demonstrated shortly before this book was written.

Labels:

disraeli,

eurobabes,

germany,

lord byron,

novels--england 19th c.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)