The pictures came up on the new format in the opposite order from that I was planning to write about the movies in. That is my problem, but it is a relevant one. Still getting used to the new Blogger. I know I should change to Tumblr or something more up to date but as yet I don't want to lose the continuity.

It's too soon for another movie post, but I'll forget everything about all of these if I don't put it down now.

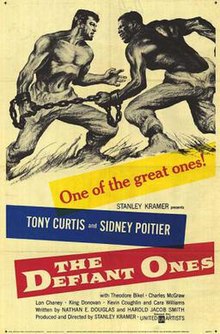

The Defiant Ones (1958)

An earnest, liberal-intended, clunky social message films of the 50s and 60s. Stanley Kramer, as far as I can make out, was the chief practitioner of this school of filmmaking, the particular methods of which are very much out of fashion these days, even with me, though certainly our day has its own didactic tendencies where its most treasured causes are concerned. I don't mind watching these movies on occasion as historical artifacts--and this one is at least less wince-inducing to sit through now than the later Kramer-Sidney Poitier collaboration Guess Who's Coming to Dinner--but there is nothing much inspired in them such as I am wont to look for.

I am considering officially adopting the opinion, based still on fairly scant experience and research, that the years 1955-1959, if not certain other ones on the fringes of these dates also frequently proposed as candidates, really were a down period for Hollywood. Going back through my essays here and recalling my previous filmwatching history, I cannot think of anything I have seen from this five year period (from Hollywood) that I either think of as really first-rate, or that made any significant emotional impact on me. I will probably now see two or three such movies in the next couple of months that give the lie to this assessment, but that is what I see at the moment.

Something that always strikes me about the films of this period compared to those of other periods, the pre-1950 era in particular, is how the world in which they take place, the sets and scenes, seems so uncrowded, uncluttered, quiet, devoid of activity and isolated. It is so noticeable to me that I have to attribute it to something affecting the collective psychology of the time, in which the very idea of a city street, a bedroom, a Sunday dinner, a dance hall, a train station, and all that one might expect to encounter there, suddenly became different from what these had been up to the 1950s. This movie completely partakes of this isolated, anomic, Twilight-Zonesque (to reference another characteristic entertainment of the period) atmosphere.

One aspect of the film I thought was good are the intermittent cuts from one of Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis's subdued and overwrought philosophical dialogues, by the end of which I was usually drifting off to sleep, to the comparatively lively (though ultimately still lackadaisical) police manhunt (the two stars are escaped convicts, one black, one white, who are chained together) usually accompanied by some groovy guitar music that one of the searchers was playing on a transistor radio.

The section with the character of the woman played by Cara Williams was ludicrous, but she herself was sturdy, handsome, loquacious, was really working the southern accent, or the imitation of one, and secretly desperate. All of which I was well in the mood for.

Tony Curtis is one of those people, whose number for me is now dwindling, but who are ubiquitous when you are a kid, who has been presented by the media as a big celebrity my entire life though his career was effectively over before I was born. Jerry Lewis is another guy in that category for me, as is George Hamilton, the guy with the tan (seriously though, what money is that cat living off of? Other than acting in a TV series that ended around 1965, what has he ever done? He's the equivalent of Gay Talese maintaining a reputation, an East Side townhouse and the most envied wardrobe in Manhattan on the strength of some magazine articles written in the 1970s). Anyway, this was the first time I had ever seen Tony Curtis, whom I have always known as fat, rather blatantly flaming in spite of having a well known wife and daughter, and prone to droning on ridiculously about his youthful beauty. He wasn't much of an actor. Sidney Poitier is better, even with the lackluster material--he at least has a presence on the screen, which, yes, besides being the only black star in Hollywood for about 15 years, is probably why he remains a somewhat memorable and symbolic figure in movie history in spite of the dated and mediocre quality of all of his movies that I have seen.

The race relations aspect of this movie, which at the time it was made was both the point and one supposes the most striking thing about it, probably will not make much of an impression among most modern viewers--while I did not forget about it in the course of watching the film, there is little about it that will be novel to most adults in 2012, who will probably find the depiction of white racism too generously understated for a movie from the 1950s.

Look Back in Anger (1959)

The especial brilliance of the Jimmy Porter character (played by Richard Burton in the movie, I thought pretty distinctively, though critical opinion as well as Burton's own apparently consider the matter otherwise) is in the depiction of how relentless the pressure and stress he inflicts on the people around him are, especially the women; he is so overwhelming that whatever they think about him is reduced to irrelevance. He becomes the only plausible sexual option because everyone else is so lifeless by comparison. He is not a suave or especially charming or likable character, but he is a force of nature, a term which in recent times seems to be exclusively applied to women; men used to be forces of nature too however. I have not come across a lot of literary characters where this relentlessness of personality has been so consistently depicted and maintained. It is an accomplishment.

One of the themes of these movies of course is that the young people in them are stuck in these dreary, hopeless lives working in a factory or something and chained for eternity to a spouse they have discovered they don't like all that much. Of course someone entering adulthood in 1960 would just have retired within the last decade or so at the earliest, and things have changed a lot--granted, instead of giving their lives to the assembly line, the pub, and unhappy marriages, the British working classes seemed to have transitioned to the dole, binge drinking, chavism and American style obesity, but still, things must have gotten brighter for some people, perhaps especially the ones who really cared about the unpleasant direction their lives seemed to be heading in.

The Virgin Spring (1960)

I am considering officially adopting the opinion, based still on fairly scant experience and research, that the years 1955-1959, if not certain other ones on the fringes of these dates also frequently proposed as candidates, really were a down period for Hollywood. Going back through my essays here and recalling my previous filmwatching history, I cannot think of anything I have seen from this five year period (from Hollywood) that I either think of as really first-rate, or that made any significant emotional impact on me. I will probably now see two or three such movies in the next couple of months that give the lie to this assessment, but that is what I see at the moment.

Something that always strikes me about the films of this period compared to those of other periods, the pre-1950 era in particular, is how the world in which they take place, the sets and scenes, seems so uncrowded, uncluttered, quiet, devoid of activity and isolated. It is so noticeable to me that I have to attribute it to something affecting the collective psychology of the time, in which the very idea of a city street, a bedroom, a Sunday dinner, a dance hall, a train station, and all that one might expect to encounter there, suddenly became different from what these had been up to the 1950s. This movie completely partakes of this isolated, anomic, Twilight-Zonesque (to reference another characteristic entertainment of the period) atmosphere.

One aspect of the film I thought was good are the intermittent cuts from one of Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis's subdued and overwrought philosophical dialogues, by the end of which I was usually drifting off to sleep, to the comparatively lively (though ultimately still lackadaisical) police manhunt (the two stars are escaped convicts, one black, one white, who are chained together) usually accompanied by some groovy guitar music that one of the searchers was playing on a transistor radio.

The section with the character of the woman played by Cara Williams was ludicrous, but she herself was sturdy, handsome, loquacious, was really working the southern accent, or the imitation of one, and secretly desperate. All of which I was well in the mood for.

Tony Curtis is one of those people, whose number for me is now dwindling, but who are ubiquitous when you are a kid, who has been presented by the media as a big celebrity my entire life though his career was effectively over before I was born. Jerry Lewis is another guy in that category for me, as is George Hamilton, the guy with the tan (seriously though, what money is that cat living off of? Other than acting in a TV series that ended around 1965, what has he ever done? He's the equivalent of Gay Talese maintaining a reputation, an East Side townhouse and the most envied wardrobe in Manhattan on the strength of some magazine articles written in the 1970s). Anyway, this was the first time I had ever seen Tony Curtis, whom I have always known as fat, rather blatantly flaming in spite of having a well known wife and daughter, and prone to droning on ridiculously about his youthful beauty. He wasn't much of an actor. Sidney Poitier is better, even with the lackluster material--he at least has a presence on the screen, which, yes, besides being the only black star in Hollywood for about 15 years, is probably why he remains a somewhat memorable and symbolic figure in movie history in spite of the dated and mediocre quality of all of his movies that I have seen.

The race relations aspect of this movie, which at the time it was made was both the point and one supposes the most striking thing about it, probably will not make much of an impression among most modern viewers--while I did not forget about it in the course of watching the film, there is little about it that will be novel to most adults in 2012, who will probably find the depiction of white racism too generously understated for a movie from the 1950s.

Look Back in Anger (1959)

I also read the original John Osborne play sometime within the last year (actually April 18, 2011, to be exact), one of about fifteen plays I read at that time which I will probably never get around to writing up my notes on here--not that this is any great loss to the public, but I believe that it sometimes provides modest benefits to myself. The dialogue is a little overwritten and awkward in the way it handles some of the scenes with the women but it knows what it is about more than most things I come across nowadays, and Jimmy Porter is really a good character, even admitting this tendency towards his being at times overwritten. I take to the films of this "Kitchen Sink" era very strongly, anyway. I feel as if the characters in them, even a nasty bastard like Jimmy, were missing friends of mine; that the way they dress, the way they drink at the pub, the way they read the newspaper or take a walk on a windy day, the way the girls look when they are sleeping, or kissing, or even the particular nature of their beauty (and the two female leads in this, Mary Ure and Claire Bloom, strike me as especially beautiful as a consequence of this), resemble what I have always perceived to be for me the most realistic, and therefore in some way most beautiful, or most poignant, manifestations of all these things more than I have found elsewhere. What does this say about me? Probably that I have more of a working class, or at least a mid-century working class mindset in me than I usually have the opportunity to fully indulge in. Am I an 'angry young man'? Perhaps in a latent sense. I find I am sympathetic to the attitude.

The especial brilliance of the Jimmy Porter character (played by Richard Burton in the movie, I thought pretty distinctively, though critical opinion as well as Burton's own apparently consider the matter otherwise) is in the depiction of how relentless the pressure and stress he inflicts on the people around him are, especially the women; he is so overwhelming that whatever they think about him is reduced to irrelevance. He becomes the only plausible sexual option because everyone else is so lifeless by comparison. He is not a suave or especially charming or likable character, but he is a force of nature, a term which in recent times seems to be exclusively applied to women; men used to be forces of nature too however. I have not come across a lot of literary characters where this relentlessness of personality has been so consistently depicted and maintained. It is an accomplishment.

One of the themes of these movies of course is that the young people in them are stuck in these dreary, hopeless lives working in a factory or something and chained for eternity to a spouse they have discovered they don't like all that much. Of course someone entering adulthood in 1960 would just have retired within the last decade or so at the earliest, and things have changed a lot--granted, instead of giving their lives to the assembly line, the pub, and unhappy marriages, the British working classes seemed to have transitioned to the dole, binge drinking, chavism and American style obesity, but still, things must have gotten brighter for some people, perhaps especially the ones who really cared about the unpleasant direction their lives seemed to be heading in.

The Virgin Spring (1960)

Ingmar Bergman movie centered around the rape and murder of a very young girl in medieval Sweden, based on an indigenous legend of that far off period. Although I am something of a Bergman fan, my instinct, or preference, in the past has been to avoid this kind of blatantly dark and unrelenting subject matter. So I have mainly only seen his comparatively happier films. Bergman was a real artist--as were a great many of the people he worked with, obviously, but his was evidently the dominant vision--and this was an important transitional movie in his progression, the style and look still retaining something of the cleaner, more youthful air of his 50s films, with the very direct confrontation with the grim and dirty realities of existence pointing ahead to the second, and in most serious critics' opinions, greater half of his career. As alluded to earlier, Bergman was always a working artist who had many projects going on in the course of a year, and the script and the way some of the themes and ideas of this movie are explored reflect that. I would not call it a wholly successful work--I certainly cannot say that I enjoyed it, if you believe that pleasure counts for anything--but it has very beautiful, memorable images, and it is frequently smart, or at least feels smart in the late Modernist, mid-century way which is my idea of feeling smart.

Though widely panned in Europe--the French I believe declared that they were finished with Bergman when this film was released--Bergman was still something of a novelty in America among the art house crowd at the time, and Virgin Spring even won the Oscar for best foreign film in its year. I know or have read of several people who were college age or just after at the time who have memories of seeing this and of its being a big deal at the time. Again, enjoying it or even having an opinion on whether it was good or not seems to have been less of a consideration than that it was just so different from what everybody here was used to as to be exciting. I like to think I would have fit in well in that milieu where young people found Bergman movies exciting, but I doubtless would not have gotten them and would have found them threatening and indecent had I actually been young at the time.

One Swedish reviewer at the time chastised Bergman for presenting an image of their country to the world as a "gloomy, introverted culture full of angst and despair." I love that quote.

The Leopard (1963)

This is going to be a speed review, as I am determined to finish this tonight. If I sense that there is any public demand for an expansion, I will try to satisfy it.The book is one of the best books of all time, and is much beloved by serious people, so I think you have to consider the movie as a movie, and separate from the book. The movie does have some worthwhile attributes. It has a major director (Visconti) who does some interesting things. I like the long, leisurely pace of the scenes, and all the usual reminders of the old lost Europe, which was one of Visconti's specialties. I was reminded that I would still like to go to Sicily sometime, and wondered anew if I ever will get there, or will ever see Italy again at all. I thought Burt Lancaster was pretty good as the Prince, Alain Delon...

My time is up. I didn't even get to talk about the bombshell Claudia Cardinale, who however I must confess finishes behind the two British girls and maybe even Cara Williams in my affections out of this group, though I know she is one of the most scintillating, take me on the floor right now babes ever to grace a movie screen.

My writing just is not likable no matter how conscientious I am about it. I hope my children turn out more likable people than I am

No comments:

Post a Comment