Back now to subjects that really matter, and whose relevance will never fade; of course I am referring to Elizabethan poetry.

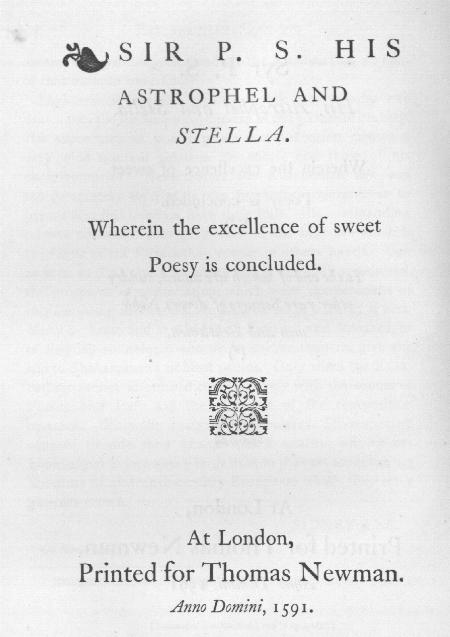

I wrote about Sir Philip Sidney's spectacular career in an earlier which I can't find at the moment. You may have noticed that I have slowly been going back and assigning labels to some of the old posts--eventually there will be a Sir Philip Sidney category. Sidney died at age 31 of an infection after being shot in the thigh fighting against the Spanish in Holland; in contrast to Laurence Sterne (whom I wrote about last week) however, his biography is packed with action and brilliant accomplishment. Obviously it helped that he was very well born, but plenty of people are well born and disturbingly never progress beyond mediocrity in any field. He entered Oxford at 13 and was graduated by 18. A portion of his recorded travels include Paris, Strasbourg, Frankfurt, Heidelberg, Vienna, Venice, Padua, Genoa, Florence, Poland, Brno, Prague, Dresden, Antwerp, and all over Ireland and England as well. At 22 he was named Cup-bearer to the queen, about the significance of which post I can't find much satisfactory hard information right at hand, but it appears to have been considered desirable. At 23 he was sent to Prague as ambassador. Member of parliament at 27. Appointed governor of Flushing in the Netherlands, which involved leading English troops in battle. Wrote hundreds of poems ("The Major Works") is 329 pages long, about 215 of which are poetry. Astrophil and Stella, a sequence of love poems, consists of 108 sonnets and 11 songs. As he did not publish his poems during his lifetime, it is considered by scholars unclear why or for whom he wrote them.

Since I have known about him, I have always regarded Sir Philip Sidney as a person whose development, preparation, experience and activity in his adolescence and twenties were pretty close to the ideal. It is one thing, and an admirable thing, to learn to cut fat out of your schedule, not waste time, be purposeful, and all that. I know many people who have succeeded in doing this however, without attaining the ideal level of development that one feels with regard to Sidney. Sidney seems to have been able either to cut the fat from his thinking or perhaps, living in the age he did, to prevent it from ever insinuating itself there in the first place. These things seem likely to be ever-increasingly harder to do in our age, though they are the most vital quality the imaginative writer of poetry especially can possess.

I read the entire Astrophil and Stella sequence back in April of 2004; as with Tristram Shandy, I was astonished by how long it had already been, for it seemed to me something I had read recently. The books I read before I had children I can place very neatly in memory with other things that were going on simultaneously in my life, seasons, outings, trips, the jobs or variety of idleness I had at the time, what rooms I lived in, bars and restaurants I went to, whether I read part of the book in the library or and what chair I sat in. Since the children were born and I have lived in the same house and had the same job everything runs together in a kind of eternal sameness. Evidently I was depressed or something at the time I read this book. My notes largely consist of sighs and 'too distracted to write about today' types of entries. Still I definitely had the impression that Sidney was a great poet, like many of the Elizabethans perhaps too great; their writing expressed their meaning and the process of thought by which they attained that meaning in such precise and perfect English that there seemed nothing really to say about them. As with Spenser, any sign of real struggle or conflict where impression, or truth, is concerned is difficult to detect. Language and perceptions are not with them, as they are to most people, further obstacles to truth, but its servants. This is what makes one find them so beautiful I think but also difficult to write about.

I read the entire Astrophil and Stella sequence back in April of 2004; as with Tristram Shandy, I was astonished by how long it had already been, for it seemed to me something I had read recently. The books I read before I had children I can place very neatly in memory with other things that were going on simultaneously in my life, seasons, outings, trips, the jobs or variety of idleness I had at the time, what rooms I lived in, bars and restaurants I went to, whether I read part of the book in the library or and what chair I sat in. Since the children were born and I have lived in the same house and had the same job everything runs together in a kind of eternal sameness. Evidently I was depressed or something at the time I read this book. My notes largely consist of sighs and 'too distracted to write about today' types of entries. Still I definitely had the impression that Sidney was a great poet, like many of the Elizabethans perhaps too great; their writing expressed their meaning and the process of thought by which they attained that meaning in such precise and perfect English that there seemed nothing really to say about them. As with Spenser, any sign of real struggle or conflict where impression, or truth, is concerned is difficult to detect. Language and perceptions are not with them, as they are to most people, further obstacles to truth, but its servants. This is what makes one find them so beautiful I think but also difficult to write about.The book I use for my reading list had a question on some lines from the 49th sonnet, so that is why I am going to write my commentary today on that one rather than on any other one.

Our horsemanships, while by strange work I prove

A horseman to my horse, a horse to love;

And now man's wrongs in me, poor beast, descry.

First off, the conceit is a good one, having not merely the usual duality of images, but with a common component between them which occupies the opposite position in the second that it does in the first. The fourth line is a little tricky, but as it is emphasized again later on that he is simultaneously riding and being ridden I believe he is encouraging his horse to expatiate on the various cruelties and other indignities he is inflicting on it, as he is about to do with regard to his own hard master.

The reins wherewith my rider doth me tie

Are humbled thoughts, which bit of reverence move,

Curbed in with fear, but with gilt boss* above

Of hope, which makes it seem fair to the eye.

boss-metal knob on the bit.

The humbled thoughts are the part I have the most trouble getting the sense of here. Humbled probably has a slightly different connotation than it does in our modern usage, though I am not sure what it would be. The original root from Latin via Old French, humilis, would translate as low, or lowly, from humus, ground. Certainly there is a hint of baseness, the whole image bespeaks a total degradation and loss of proper manhood on the lover's part. Also we are told directly that the bit of reverence only seems fair. Delusion and denial of one's proper state abound.

Girt fast by memory; and while I spur

My horse, he spurs with sharp desire my heart;

He sits me fast, however I do stir;

I am not quite clear on the wand image. I assume it refers to the switch which one lashes the horse with. But then what is meant by will? The rider's will? Or the beast's, to be driven and overmastered by his rider.

And now hath made me to his hand so right

That in the manage myself takes delight.

I guess this clarifies a little my question about the wand.

The GRE questions on this poem were:

1. The poet's portrayal of "Love" (l.1) is an example of:

A. personification B. metonymy C. synecdoche D. apostrophe E. dead metaphor.

Uh...I'm going to go with A. Gut instinct and all that.

2. Horsemanships (l.2) is plural because:

A. love rides the speaker while the speaker rides his horse. B. the speaker has committed more than one wrong. C. love exercises many forms of control over the speaker. D. love controls him better than he controls love. E. love appears in many forms.

Dare I suppose that the answer is 'A' again?

These were too easy. I got both right.

What I'm getting out of the Elizabethans is not much in the way of philosophy or ethics for the most part, but their imaginative approach to language and understanding the world was developed to a far greater degree than in any other period of English literature, the use of language to elevate and expand the possibilities of what are, in many instances, fairly common thoughts and impressions. This is the secret of all great literature and art I guess, and every age is to an extent seeking the means to figure out how to do this freshly and as the times require. If we don't remind ourselves of this out loud from time to time however we won't even remember what it is we are looking for.

No comments:

Post a Comment