Monday, March 29, 2010

Gil Roth over at Virtual Memories is an excellent linker (look at this, for example), something of which I do not do very much. I had wanted to comment on several items he had posted about in the past few weeks but when, as usual, I was unable to do so either succintly or quickly, I thought I would just do my own post of some of these items.

David Shields

There was a link to a new book by this guy which I can't find now, the premise of which is that Shields thinks the novel as we have think of it is essentially dead and a new approach to writing about the kinds of subjects that have in recent centuries have been dealt with by novels, updated to the consciousness and thought processes of our contemporary times, is demanded. The book got some attention for a week or two and then, as usually happens, everyone quickly moved on. My comments weren't going to be about the subject of the book--as far as I have an opinion, it is that novels succeed or fail largely based on how compelling their voice is, and while innovation often proves to be the means for a compelling voice to emerge, I think the innovation is more likely to emerge out of the needs of the voice than vice versa--but because David Shields was one of the professionals at the writing conference I attended and I was going to write my observations regarding his personality.

At this point I paused to consider whether this sort of impression was something one ought to write about a living person whose level of fame and sales are probably not all that much higher than mine are. It is not quite the same thing as saying that one once met, say, Salman Rushdie and thought he was a jerk (for the record, I have not met him). There would not be much of a likelihood of him or one of his friends reading my commentary, nor of his being affected by it one way or the other. However, seeing as Shields evidently is pleased to offer himself as a provocateur of significance with more than the usual edge to him, one would suppose him either far above the level of being capable of having his feelings hurt by the likes of me, or at least flattered by the attention.

So David Shields, when I had the opportunity to observe him pretty near to hand, was around 50 years old but looked much younger, at least six foot three with a shaven pate, and he appeared to be relatively fit. Combined with the attitude he tried to affect, one would suspect him to convey an air of authority, but he did not do this. What he did convey was an odd combination of self-loathing, part fairly blatant frustration at not having achieved the literary success even of people like Jonathan Franzen, let alone the likes of Flaubert and Mann whom he had imagined himself contending with as a young man, and part largely, it seemed, centering around the incovenient circumstance of his undeniable whiteness, which I will expound upon below, and an air of "but I'm still better than you" aimed at the placid, mostly white people who doubtless constitute the overwhelming majority of his university students and whatever audience he has. At the time he had just published an earnest, respectful book about the culture of the NBA--he had spent a season covering and travelling with the Seattle Supersonics I believe, and he was still very much in thrall to the dynamism of black culture and the wondrousness of black physicality, especially when set against the polite, bloodless, sexless worlds of university English departments and writer's conferences which gave him his living, but towards which he appeared to feel an ambivalence that flirted mightily with revulsion and contempt. So the minute I read about this new book I was immediately reminded of all these things.

The Great Books

The second link was to an article about a book about the Great Books (author: Alex Beam), which included a visit to my alma mater, St John's College. Most of the reviewers of the book seem to have thought the college came off badly in this section. Since I admit to a curiosity about what the mainstream educated society makes of the college, because by extension it is largely the same as what it must make of me, I got the book from the library and read the chapter on St John's. I thought the school actually came off rather well. The depiction of what it is like seemed more accurate to me than what is usual in these kinds of accounts, and my experience and point of view being what it is, the impression made on me was a positive one. This is not evidently how it reads to people without connections to the college however.

St John's is, I suppose, an odd place, quaint, always behind the times, populated by people with whom it seems to be supposed by most reporters his readers at this stage of historical development must have very little in common. It is sort of like the Gibraltar of the American college system, which tiny colony sophisticated visitors frequently describe as being in all the worst ways as like being in a provincial British town in the 1950s and basically feeling incongruous with life as it is supposed to be in the 21st century. And it is true that the typical class, especially lab class, on a day-in, day-out basis is not very scintillating. Very rarely does one walk out of any class with some specific, measurable morsel of learning that will belong to him forever henceforth and be directly practicable in a multitude of circumstances. Sometimes things that are said or that one reads lodge somewhere in the mind and then years afterward the meaning or significance of them become somewhat more clear. This conception of the educational process is not something in which the modern world as a whole has much trust, and perhaps for those at the far right end of the cognitive spectrum, largely rightfully so. Much of the tangible learning that does go on is admittedly of a basic nature, the progress of intellectual history, the nature of language and translation, the very basic fundamentals of music, introduction to major books (Homer, Plato, Dante, the Bible, etc.), the sorts of things one arguably should have learned in high school; most people of course, even bright ones, don't learn them in high school anymore however. History and writing are considered by many people both in and out of the college to be two major areas where the curriculum is weakest, though personally I found them to be among the subjects where my understanding advanced the most during my time there. Most of the people in a bad lab class are people who would probably never have taken any kind of science class had they gone to another college, which might be taken into consideration before denouncing it as having no value, for the students are intelligent enough that three years of attendance, exposure, writing papers and so on gives them some greater, if still amateurish, understanding of the subject compared to what they had before. I suppose that the argument I think is, for $50,000 a year, that's not enough, and besides all the Great Books, even Plotinus, are available online for free now if you really want to read them anyway. Obviously one has to put his own value on what things are worth. In spite of all my shortcomings and what would be perceived by most people to be my unimpressive income and career accomplishments, I think the improvement in the overall quality of my life compared to if I had never gone there, or somewhere pretty similar, justifies the expense accrued by me and my family certainly (which, as I attended 20 years ago and received aid, the direct cost to me was not anywhere near the amount quoted above). The case that the expense borne by the taxpayers for my education was wholly worthwhile is perhaps harder to assert, though I am comfortable in asserting that I think the national economy has, or will have, recovered its investment where I am concerned. Only the college itself has yet to reap either financial dividend or the satisfaction of basking in any reflected glory from my accomplishments commensurate to the generosity they showed towards me. I think it is true that people with world class talent in some area where cultivating that talent requires rigorous study under the tutelage of the very top professionals in the field or even who already have an advanced level of proficiency in Greek or mathematics or physics beyond what St John's can contribute to need to seek a place that is suited to their particular requirements. I suspect this is a very small portion of even the most brilliant (top 2% or so) of eighteen year-olds.

I was going to comment as well about the Gamma Male phenomenon, but as this post is already so long, the subject is such a large one and so peculiarly suited to my particular expertise I am sure I will have many opportunities to return to it in the future.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Back now to subjects that really matter, and whose relevance will never fade; of course I am referring to Elizabethan poetry.

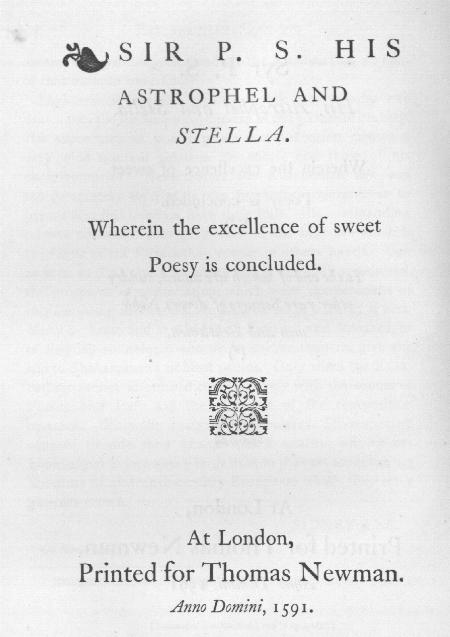

I wrote about Sir Philip Sidney's spectacular career in an earlier which I can't find at the moment. You may have noticed that I have slowly been going back and assigning labels to some of the old posts--eventually there will be a Sir Philip Sidney category. Sidney died at age 31 of an infection after being shot in the thigh fighting against the Spanish in Holland; in contrast to Laurence Sterne (whom I wrote about last week) however, his biography is packed with action and brilliant accomplishment. Obviously it helped that he was very well born, but plenty of people are well born and disturbingly never progress beyond mediocrity in any field. He entered Oxford at 13 and was graduated by 18. A portion of his recorded travels include Paris, Strasbourg, Frankfurt, Heidelberg, Vienna, Venice, Padua, Genoa, Florence, Poland, Brno, Prague, Dresden, Antwerp, and all over Ireland and England as well. At 22 he was named Cup-bearer to the queen, about the significance of which post I can't find much satisfactory hard information right at hand, but it appears to have been considered desirable. At 23 he was sent to Prague as ambassador. Member of parliament at 27. Appointed governor of Flushing in the Netherlands, which involved leading English troops in battle. Wrote hundreds of poems ("The Major Works") is 329 pages long, about 215 of which are poetry. Astrophil and Stella, a sequence of love poems, consists of 108 sonnets and 11 songs. As he did not publish his poems during his lifetime, it is considered by scholars unclear why or for whom he wrote them.

Since I have known about him, I have always regarded Sir Philip Sidney as a person whose development, preparation, experience and activity in his adolescence and twenties were pretty close to the ideal. It is one thing, and an admirable thing, to learn to cut fat out of your schedule, not waste time, be purposeful, and all that. I know many people who have succeeded in doing this however, without attaining the ideal level of development that one feels with regard to Sidney. Sidney seems to have been able either to cut the fat from his thinking or perhaps, living in the age he did, to prevent it from ever insinuating itself there in the first place. These things seem likely to be ever-increasingly harder to do in our age, though they are the most vital quality the imaginative writer of poetry especially can possess.

I read the entire Astrophil and Stella sequence back in April of 2004; as with Tristram Shandy, I was astonished by how long it had already been, for it seemed to me something I had read recently. The books I read before I had children I can place very neatly in memory with other things that were going on simultaneously in my life, seasons, outings, trips, the jobs or variety of idleness I had at the time, what rooms I lived in, bars and restaurants I went to, whether I read part of the book in the library or and what chair I sat in. Since the children were born and I have lived in the same house and had the same job everything runs together in a kind of eternal sameness. Evidently I was depressed or something at the time I read this book. My notes largely consist of sighs and 'too distracted to write about today' types of entries. Still I definitely had the impression that Sidney was a great poet, like many of the Elizabethans perhaps too great; their writing expressed their meaning and the process of thought by which they attained that meaning in such precise and perfect English that there seemed nothing really to say about them. As with Spenser, any sign of real struggle or conflict where impression, or truth, is concerned is difficult to detect. Language and perceptions are not with them, as they are to most people, further obstacles to truth, but its servants. This is what makes one find them so beautiful I think but also difficult to write about.

I read the entire Astrophil and Stella sequence back in April of 2004; as with Tristram Shandy, I was astonished by how long it had already been, for it seemed to me something I had read recently. The books I read before I had children I can place very neatly in memory with other things that were going on simultaneously in my life, seasons, outings, trips, the jobs or variety of idleness I had at the time, what rooms I lived in, bars and restaurants I went to, whether I read part of the book in the library or and what chair I sat in. Since the children were born and I have lived in the same house and had the same job everything runs together in a kind of eternal sameness. Evidently I was depressed or something at the time I read this book. My notes largely consist of sighs and 'too distracted to write about today' types of entries. Still I definitely had the impression that Sidney was a great poet, like many of the Elizabethans perhaps too great; their writing expressed their meaning and the process of thought by which they attained that meaning in such precise and perfect English that there seemed nothing really to say about them. As with Spenser, any sign of real struggle or conflict where impression, or truth, is concerned is difficult to detect. Language and perceptions are not with them, as they are to most people, further obstacles to truth, but its servants. This is what makes one find them so beautiful I think but also difficult to write about.The book I use for my reading list had a question on some lines from the 49th sonnet, so that is why I am going to write my commentary today on that one rather than on any other one.

Monday, March 22, 2010

I Try to Justify My Lack of Attention to Things Like the War

Monday, March 15, 2010

(This guy actually looks a little like what I imagine the young Tristram, who is about this age for a good portion of the book once he manages to introduce himself into the story, looked like. In any event he definitely has more of an 18th-century appearance about him than most of the other kids nowadays).

(This guy actually looks a little like what I imagine the young Tristram, who is about this age for a good portion of the book once he manages to introduce himself into the story, looked like. In any event he definitely has more of an 18th-century appearance about him than most of the other kids nowadays).I have been meaning to do a post on this for a few months. I actually read the book back in June of '03 (which lapse of time astonishes me; I thought it had been much more recently), but, I saw the recent movie which took it up as its organizing inspiration sometime last fall, around which time I also saw the book referred to in several other places in ways which for one reason or another bothered me; so I thought I should write something about it from my perspective, for I guess I don't like what I perceive most of its readers to be primarily choosing to take from it. Why would I even care? Well, I don't care that much, but it is, or ought to be, one of the greatest of all books in English, and there is a certain quality in it that I seem to strongly desire to feel that other people share my particular enthusiasm for, which I somehow consider never quite to be the case.

Though I will probably overwrite here, my points are but simple ones, and are not intended to dismiss several centuries worth of deep scholarship and analysis. This analysis is not on the whole what is interesting and noteworthy to me about the book however.

Though I will probably overwrite here, my points are but simple ones, and are not intended to dismiss several centuries worth of deep scholarship and analysis. This analysis is not on the whole what is interesting and noteworthy to me about the book however. It would be ridiculous for me not to try to explain what I mean when I refer to the book's having 'magical' qualities. This is really just the writing, which is as utterly natural and clear and precise as any imaginative work in the language while at the same time the sensibility and approach to the narrative are equally unique. It is pretty much unlike anything else that exists in literature, nearly every little chapter a singularly finely cut and polished jewel, but with a skill in characterization, setting and dialogue that is Dickensian, even surpassing Dickensian; for while most of the dialogue and activity and thought in naturalistic terms amount to quite a bit of nonsense, rarely have more complete and vivid depictions of individual fictional intellects and personalities emerged out of the arrangement of words on a page. What is more, his technique is apparently virtually inimitable, for I have to think far more people would write in this manner, which is both fresh and immediately effective, if they were at all able. The only reason I can think of for its not being more highly loved than it is among people who are not in some way professional literary critics is that it is easy to be sure one doesn't understand it the way one is supposed to, which makes one hesitant to talk about it and therefore to be able regard it as an influence or model. But this is all I will try to say about it for the time being.

It would be ridiculous for me not to try to explain what I mean when I refer to the book's having 'magical' qualities. This is really just the writing, which is as utterly natural and clear and precise as any imaginative work in the language while at the same time the sensibility and approach to the narrative are equally unique. It is pretty much unlike anything else that exists in literature, nearly every little chapter a singularly finely cut and polished jewel, but with a skill in characterization, setting and dialogue that is Dickensian, even surpassing Dickensian; for while most of the dialogue and activity and thought in naturalistic terms amount to quite a bit of nonsense, rarely have more complete and vivid depictions of individual fictional intellects and personalities emerged out of the arrangement of words on a page. What is more, his technique is apparently virtually inimitable, for I have to think far more people would write in this manner, which is both fresh and immediately effective, if they were at all able. The only reason I can think of for its not being more highly loved than it is among people who are not in some way professional literary critics is that it is easy to be sure one doesn't understand it the way one is supposed to, which makes one hesitant to talk about it and therefore to be able regard it as an influence or model. But this is all I will try to say about it for the time being.Friday, March 12, 2010

One of these days I am going to get around to writing some serious examinations of major issues confronting humanity in this ever darkening age, but I have been distracted this week by memories of certain songs that were constantly in the foreground of my consciousness nineteen years ago. In one of those odd transformations of perception that afflicts the mind, it now seems much longer than 19 years have passed since the songs I am about to present were in heavy rotation in the atmosphere about my life, whereas up until fairly recently that time had seemed to me much nearer than in fact it was. As for waiting until the 20th anniversary of that pivotal year to do my commemoration, I am sure if I did the event would come out stilted and artificial. I remember conceiving the idea of making a big statement on the 75th anniversary of the Armistice in '93, and then finding myself unable to pull such a statement together. I would have been much better off doing it on the 74th.

This all started because I the commercial for a stupid Reggie Miller versus the Knicks documentary on ESPN that was playing on the radio was using the riff for this song. I couldn't place the name of the song for a couple of minutes, but it took me to a very specific place; not a particularly great place, the parking lot of the old shopping center in Parole, Maryland, the occasion for my being there I have no recollection of, but I know that it was sometime in the late summer of 1991, sending a fairly strange chain of associations into motion.

I say strange because the immediate next leap from LL Cool J was to the Go-Betweens, and this song that had about a two week run as a hit in our dorm, and then just as rapidly disappeared, and which I had also not thought about in eons. This clip apparently is not the actual video for the song, though it fits the mood of it perfectly. I have no idea what the Go-Betweens actually look like. Somebody had this song, and played it, and I liked it, and that was about as far as it went.

From that the next step was to the Velvet Underground, which during the long and dark, though not as I remember especially cold, January through March of '91, received almost daily airplay. It was always said of this group that they were ahead of their time, and I think that is correct; to me anyway they will always belong much more of the spirit of 1991 than of 1967. While this analysis coincides neatly with the period of my highest susceptibility to them, I do think there is something in it. Their particular attitude and rather pessimistic relation to the world, had become pretty mainstream by the early 90s compared to 1967, it seems to me. Anyway, for them it is hard to pick just one song, but I will choose the two most melancholy ones to fortify the memory I am calling up, Sunday Morning and, of course, Stephanie Says.

The Pogues are perhaps obvious, but I did down an awful lot of booze and sucked on a lot of cigarettes--I'm drinking some Labatt's Blue in a can right now, in fact--to this song over the years.

This one doesn't really fit in with the rest, and I don't really like it, but through association I have to include it. This was what the 6'4", 270 pound guy in the room next to me used to crank full blast when he was getting psyched up for an intermural sports game, or (much more rarely), if he was meeting some lady or other of an evening. This guy was a much less intimidating figure on the playing field than his size might suggest, mainly because he could rarely make it 30 seconds into any contest without suffering some injury that would debilitate him for the rest of the game. There are always a handful of guys around like this, who are constantly afflicted with some ailment, and for whom crutches, casts, braces, etc, come to constitute a regular facet of their general look. This fellow I'm speaking of was more commonly weighed down by ice packs than crutches on the sideline, though once he was stung by a bee and was laid up in bed for the better part of two weeks. It had nearly killed him, at least that was what was reported. Kidding aside, on the two or three occasions a year when he managed to make it through a whole game, his unusual and rarely seen array of skills would catch his opponents off guard a couple of times in the course of a game. In basketball he had a kind of Gheorghe Muresan style offensive package where he never got off the floor. One time he went up fully extended for a shot and I flew at him and, as he pulled it back at the last minute, right past him, after which he proceeded to casually lay it in, no up-and-down in the least. In softball he actually had kind of fearsome power for our league, though the lack of a DH rule definitely hurt him, for he frequently injured himself playing defense and running the bases.

I didn't actually listen to this with other people, but I saw it on 120 minutes and always thought it was a cool song and video, not to mention the essence of all things 1991 down to its ashes.

And yes, we listened to the Smiths a lot too. This was an especial favorite of that season. And this one. And one more.

I can't find a video for the last song I was going to do, which had an elaborate story that went with it anyway, so I will save that for either another time or, more likely, never.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

I figured everyone would want to see Defoe's grave. These are from way back in '96. I was alone on this particular occasion and I didn't make any friends so, no people in the photos, breaking the first rule of tourist photography. I should have taken the opportunity to figure out how to use the camera. I was reading that the first time Buster Keaton was shown a movie camera he took it apart and examined all the things that could be done with it. It fired his imagination. Meanwhile I stumbled about looking unsuccessfully for artistic shots.

1. Defoe was buried in the Bunhill Fields, a very small cemetery in Finsbury, just east of the City, near the Angel and Moorgate subway stations. I suspect a good many of the tombs have been plowed under over the years. The famous guys, besides Defoe including Bunyan, Blake, and the poet Isaac Watts, who wrote the lyrics to a sizable chunk of the standard Episcopalian Hymnal, have had their monuments gathered in the center of this little ground for the pilgrim's convenience. The rest of the remaining graves are enclosed within fences and are not open to be wandered among. Blake died in 1827, and there doesn't seem to have been many new residents added since about that time. Thus you have a very, very small, semi-preserved corner of old London here, though the modern city still pretty much rises and buzzes around you the whole time.

1. Defoe was buried in the Bunhill Fields, a very small cemetery in Finsbury, just east of the City, near the Angel and Moorgate subway stations. I suspect a good many of the tombs have been plowed under over the years. The famous guys, besides Defoe including Bunyan, Blake, and the poet Isaac Watts, who wrote the lyrics to a sizable chunk of the standard Episcopalian Hymnal, have had their monuments gathered in the center of this little ground for the pilgrim's convenience. The rest of the remaining graves are enclosed within fences and are not open to be wandered among. Blake died in 1827, and there doesn't seem to have been many new residents added since about that time. Thus you have a very, very small, semi-preserved corner of old London here, though the modern city still pretty much rises and buzzes around you the whole time. 2. If you want to read the incscription on the tomb, which is dated 1870, 139 years after Defore actually died. I forget what happened to the old tomb, or if simply wasn't grand enough for the sensibility of the times.

2. If you want to read the incscription on the tomb, which is dated 1870, 139 years after Defore actually died. I forget what happened to the old tomb, or if simply wasn't grand enough for the sensibility of the times.Monday, March 08, 2010

Though published eighteen years before Pamela officially got the era of the novel underway in English, this is certainly a very near ancestor of that beast, if not a full-blooded member of the family. Like many old ur-novels of this type, including Don Quixote, it starts off quite rough, but eventually finds a kind of rhythm that hurtles it forward. A modern writer would have gone back and corrected the beginning once he found his bearings, incorporated more smoothly into the rest of the book, but this was apparently not thought important in 1720; the origins of the genre, we are told, being humble, and it being held in low esteem by the real literati of the day, no doubt accounts for this neglect. The evocation of atmosphere, details and other textures--houses, sense of place, possessions, all the things that I like, are also rather spare by more recent standards. Everything is in the service of relating the story in as straightforward a manner as possible. As far as there is any literary decoration, it would be the good number of sly observations on human nature and society that are dropped in from time to time among the narrative.

Though published eighteen years before Pamela officially got the era of the novel underway in English, this is certainly a very near ancestor of that beast, if not a full-blooded member of the family. Like many old ur-novels of this type, including Don Quixote, it starts off quite rough, but eventually finds a kind of rhythm that hurtles it forward. A modern writer would have gone back and corrected the beginning once he found his bearings, incorporated more smoothly into the rest of the book, but this was apparently not thought important in 1720; the origins of the genre, we are told, being humble, and it being held in low esteem by the real literati of the day, no doubt accounts for this neglect. The evocation of atmosphere, details and other textures--houses, sense of place, possessions, all the things that I like, are also rather spare by more recent standards. Everything is in the service of relating the story in as straightforward a manner as possible. As far as there is any literary decoration, it would be the good number of sly observations on human nature and society that are dropped in from time to time among the narrative.That was about all I could muster to say about the book at the time I read it. It marks a significant development in English literary history and I am glad to have gone through it and become familiar with it, but on the whole I found Moll and her world to be only very faintly perceptible, three-dimensional, whole, alive, what you please, to me. There was nothing in it that was really fascinating to me.

Great Picture Here of the Modern Imagination Firing on Autopilot. There appear to be at least four or five film or television adaptations of the novel, though none as far as I can tell is rated as especially fine. Obviously the elements of the story would have cinematic appeal, though in what form is not something that shines through in the book itself. I would imagine that the interpretations are wildly varying and perhaps even outrageous.

People familiar with the story may recall that after being orphaned, Moll managed to be taken into the house of some gentlepeople where she claims to have had a proper upbringing, dancing, French lessons, refined manners, only to get into trouble when she allows herself to be seduced by the family's eldest son. I used to think that the tone of the narrative in most of the rest of the book was not consistent with this education, but I have since come to understand that it is difficult to keep up certain postures if one falls out of regular contact with the circles where one acquired those postures.

People familiar with the story may recall that after being orphaned, Moll managed to be taken into the house of some gentlepeople where she claims to have had a proper upbringing, dancing, French lessons, refined manners, only to get into trouble when she allows herself to be seduced by the family's eldest son. I used to think that the tone of the narrative in most of the rest of the book was not consistent with this education, but I have since come to understand that it is difficult to keep up certain postures if one falls out of regular contact with the circles where one acquired those postures.There was a point around a third of the way into the book, when Moll is working on about her third husband, in addition to several other past lovers, when the demands of chastity in a new ongoing situation became ridiculous, and despite some great arguments regarding the matter, the struggle wearied me.

The cleverest episode in the book was the one where Moll and a male counterpart mutually deceive themselves into marriage, she by intimating that she possesses a fortune, he by posing as the owner of a large estate in Ireland. When the deceptions are found out (the man opens his letter of confession to her "My dear--I am a dog"), though they have grown fond of each other, they call the marriage off anyway to better pursue their respective self-interests.

One of the favorite pastimes of contemporary critics is to complain that modern literary novelists don't pay any attention to the primal struggles and machinations of ambitious people in the pursuit of wealth, which is after all perhaps the driving narrative of all human existence, especially at this point in history. I doubt in the long run this that this will seem true of our era, but certainly there are plenty of people in the MFA/writers' workshop/conference circuits seem to exist in a world of rather languid plenty. Given that many of them procure a sizable income themselves and follow the modern upscale lifestyle of exercise, healthy eating, 3.6 university degrees and 2.2 fellowships per person, it is obvious that they do not suffer from too great a deficiency of energy in ordinary life, it is only in their literary (and perhaps sexual) activity that they become sapped of vigor. Not having any of the difficulties, with the possible exception of sexual/romantic ones, which dog ordinary people--money, school, oppression, lack of self-control, the police, the legal system, macro-inferiority complexes--finding any drama in life becomes a struggle. Hence we have a deluge of books by people with glittering academic and professional credentials who apparently find taking care of a baby completely overwhelming. There is a kind of artist's poverty, a combination of sporadic or under-employment, debt, a certain level of squalor and discomfort which is marked by sparseness rather than grossness, leavened with regular exposure to interesting and lively people and ideas, that seems to be optimal for the imaginative faculties but also seems very hard to re-create in society as currently constituted in the necessary form.

Robin Wright as Moll in Another Adaptation. Evidently she was not good in this.

p.180--A breakdown of Moll's history, which is impressive: "...how is this innocent gentleman going to be abused by me! How little does he think, that having divorced a whore, he is throwing himself into the arms of another! that he is going to marry one that has lain with two brothers, and has had three children by her own brother!...one that has lain with thirteen men, and has had a child since he saw me! Poor gentleman!"

p.180--A breakdown of Moll's history, which is impressive: "...how is this innocent gentleman going to be abused by me! How little does he think, that having divorced a whore, he is throwing himself into the arms of another! that he is going to marry one that has lain with two brothers, and has had three children by her own brother!...one that has lain with thirteen men, and has had a child since he saw me! Poor gentleman!"

This reminds me of how powerful the effects of the electronic revoluton, cameras, cell phones, lack of necessity of carrying cash, etc, on street crime, robbery and so on, the nature of which hadn't changed much between 1700 and the mid 1990s, have been in the fifteen years since then. You don't seem to read much about people getting mugged or robbed on the street anymore compared to when I was a kid, or maybe I just am not paying attention.

Like many older (pre-1900) as opposed to newer novels, this one did pick up the longer it went. The technique of accumulating characters and incidences which build on their own momentum in the service of the story and don't whirl out in a variety of directions is evidently more difficult to master than it looks

My edition--the Heritage Press, 1942--is illustrated by probably a hundred pen and ink sketches executed in lines and curves and other flourishes. I don't know what the technique is called, but the effect is more like cartoons than exact representation. I didn't like them so much at first but they grew on me. I should have scanned one for display here. There don't seem to be any of them posted elsewhere on the internet.

Moll sails to Virginia at the end, noting that they entered "the great river of Potomac". Unlike the ancient rivers of Europe and Asia and Africa and some of our celebrated western rivers in North America, one doesn't often see or think of our eastern rivers celebrated as 'great' either in literature or song or art, with perhaps the Hudson as an exception, but quite a few of them certainly are, the Delaware, the St Lawrence, the Connecticut.

More on Virginia, it was noted that it "did not yield any great plenty of wives". They aren't lying there (I never had any very good luck with the ladies from that rich and stately commonwealth). I also noted that Moll Flanders managed to journey to America twice in her life (and once back to England) despite not living in an era of cheap airfares, so maybe there is some hope that when Peak Oil, the Global economic meltdown, etc, comes to pass, that the majority of us will not all be trapped wherever we happen to be for all time afterward as some predict, but that some limited brand of movement will be on offer.

There is maybe more in the book than I am giving it credit for. There are better 18th century novels, and I am sure at the time I was comparing it to those and finding it lacking, but it has endured better than almost anything else from its time, and is still in print from a major house as I speak.

Thursday, March 04, 2010

But as with everything else, producing one even halfway good is not as easy as it ought to be. What a truly odd exercise this whole business of existence is.

Political Update. My understanding of the current crisis in the economic situation, if not the crisis itself, is very slow-developing and perhaps obvious, but I don't like the drift of things. Among anybody who still has anything, their entire focus seems to be on preserving what they've got at all costs, without much thought for the millions who are facing impoverishment and ruin, which I don't think can be a sustainable approach. I am disappointed by the lack of wisdom and leadership being displayed on this issue by the most able classes, those who perhaps alone still have a relatively strong future to anticipate. The near 20% real unemployment rate, with bankrupt governments and no recovery of real jobs to live on any kind of mass scale anywhere on the horizon, is a problem that somebody is going to have to own, and come up with some kind of better vision for its resolution than widespread homelessness, squalor and general societal breakdown. Is nobody on the side of the increasing large portion of the populace without any real promising prospects?

Literary Update. On a positive note, somebody bought one of my books. This marks a real milestone for me, as it is the first time anybody has paid for a piece of my writing. I hope to God whoever it was bought the download for $5.95 rather than the $45+ book. I have been meaning to organize and make available a paperback version, which would be cheaper. In any event I am very moved at having sold a book, though...oh, I will let it go at that. I do really need to write another one though, before I lose whatever knack I have for it altogether.

Literary Update II. For about the last six months I have been occupied with reading really long, earnest, hyperrealistic and exhaustingly overstuffed Edwardian novels. First there was H.G. Wells's Tono-Bungay (460 pages), then Arnold Bennett's The Old Wives' Tale (640 pages), and, last but decidedly not least, Dorothy Richardson's 13 volume monument to extreme navel-gazing, Pilgrimage (2,110 pages, of which I am approximately on page 1,752). The first two of these books weren't bad, though of Bennett I preferred the thinner Anna of the Five Towns, which I read sometime back around 2003, and there is a really good 250-300 page novel that could be hammered out of the Richardson, I think. Over the course of the winter I could feel this endless reading combined with other tiresome aspects of day to day existence wearing me down. So I decided not to take Pilgrimage to Florida with me, opting instead for the somewhat famous account of 1970s Hollywood, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, (or How the Sex, Drugs, and Rock and Roll Generation Saved Hollywood). Hollywood books are an odd genre to come upon after you've been devoting yourself to self-consciously serious literature, history, etc, for a number of years. For one thing there is more speculation and conjecture than there is even in Plutarch ("it was observed by several people that her mother spent an unusually long time in the casting director's office the day she got her big break"), and anonymous sources are relied upon liberally. That said, I was rather burned out on high seriousness and the relentless Sturm und Drang of contemporary politics and economics, so I enjoyed much of the book, especially the parts set in the late 60s and early 70s before the era started to play itself out.

I have never considered myself an especially big fan of the movies of the 70s, though I realize that that is in part because I haven't seen that many of them. Most of the ones I've seen that they talk about in the book I guess I do like, though none of them are favorites, nor did I ever especially like most of the famous stars or directors featured in the book, though I did find myself interested in all the sex and power games, all which was more or less rawly expressed and experienced. One might wonder why I have become interested lately in the culture of (old) Hollywood rather than that of the army, or the biotechnology world, or Wall Street, or politics, or even art and music, which I seem to have written about more a couple of years ago. Maybe the sense that America, at least as I knew it, is collapsing, is making me nostalgic for a time when ordinary red-blooded middle-class Americans--which is the background from which most of the figures in this book emerged--were interested in things like sex and art as participants and not merely as theorists or consumers, and who actually managed to make some things happen in those directions. Though it is a little late for me to be studying this, I am always interested in how people manage to become successful in the arts. Having bought into the notion as a young man that being an artist is a good calling for morose and senstive people, I underestimated the amounts of energy and hustle that are desirable both to animate your work, but also to establish the relationships you need to get yourself into a position where people are willing to pay you. Even Warren Beatty, who seems to have more of both of these qualities than almost anyone who ever lived, in addition to other advantages, needed to employ them pretty much relentlessly to ensure himself of a career. At the same time filmmaking, as it is presented in this book, seems in comparison with playing in an orchestra, or opera singing, or ballet, or even acting in high level live theater, not to require an especially extraordinary amount of education or training to be successful. Steven Spielberg's background before getting hired by a studio for TV work at age 21 seems to have consisted of watching a lot of television and largely teaching himself how to use a movie camera, which wouldn't get you a sniff of the stage at Beyreuth. The process of filmmaking also appears to be far more messy and unpredictable than would be possible in most of the traditional high arts. The final form of most films that end up being regarded as classic often seem to be wholly unanticipated even by the filmmakers themselves until they are very deep into the process.

Peter Bogdanovich seems to be the 70s director most like myself both in temperament and approach. He had a good sense of what movies ought to look, and perhaps more significantly, feel like, but was openly derivative and not a great generator of original ideas and material. His two best movies, The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon, both of which I like, were atmospheric period pieces he was basically assigned to. He would probably have had a better career in the system of the 30s and 40s which he was obviously perhaps over enamored of. He seems to have been well-matched with his first wife, who appears to have been smart and had some artistic talent as well, doing the set design on his more successful earlier movies, but having been a nerd in his youth he threw her over for a bimbo when the opportunity presented itself, his infatuation with whom is certainly presented in the book as contributing to the premature fizzling out of his talent, which sounds like something I might have stumbled into if I had suddenly made it in Hollywood at age 32 or whatever. There is a story in the book where the very young Victoria Principal came up to the at that time still geeky but rising Spielberg in the Universal cafeteria, thrust her breasts in his face and said "I'd like to get to know you better." I mean, Victoria Principal is the kind of person who doesn't excite me at all at a distance, but I have a feeling six inches away it would have been a somewhat different matter (obviously I mean in 1974, not now). Bogdanovich apparently also became really obnoxious and arrogant during the years when he was at the height of his success, which I could easily see myself becoming if I were ever to attain any status whatsoever anywhere.

The part where a completely drugged out and raving Dennis Hopper was excoriating the audiences that stayed away from his (apparently unwatchable) The Last Movie as not wanting to do a lot of thinking reminded me that the whole book has a kind of early baby boomer mindset wherein one can recount an anecdote such as this as if it were not in fact entirely absurd.

Another instance of this ur-baby boomer mindset are the general low level of regard for the mainstream culture, Hollywood in particular, of the 1940s and 50s. At one point the author (Peter Biskind is his name, by the way), in describing the new generation of cinephiles that emerged in the 60s, singles out as one of their characteristics that "they knew John Ford was better than William Wyler, and why." I have never actually understood why this is obviously so, though almost every reputable film scholar considers the matter to be beyond doubt. I haven't seen a lot of John Ford, but what I have seen (The Quiet Man and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon) has not blown me away, while obviously I think highly of many of Wyler's films, including some of the lesser known ones like Counsellor at Law, which I wrote about last fall and which I was really impressed with.

Maybe executives at multi million dollar companies still take tons of drugs at work like Hollywood people did in the 70s but somehow I doubt it.

The sexual hysterics among people in their 30s and even older in this era, married or not, is also like reading something out of science fiction. Maybe I need to be taken out and shown more, but the people of my generation just hit 25 or maybe 30 and basically threw in the towel as far as developing any kind of sensual side of themselves went. I mean, God, the French and other international playboy types are just getting started at that age, and the Americans are packing it in with 40, 50 years to live.

Margot Kidder slept with almost everybody who came to her party house, yet I still came out of the book with a mild crush on her. As with my Victoria Prinicpal repsonse, this is not a good instinct on my part, given my personality and so on.