I took eleven pages of notes on this book, or such of it as I was able to find, but for my own sake as well as any potential reader's I am going to try to pare my observations down as much as possible. Having somewhat introduced the subject in the last post I will just briefly touch upon the main theme of the book, which is that the art and architecture of Venice from the origins of the city as a distinct society up until the early 1400s, if perceived properly, testifies to the ever-increasing wisdom, virtue, piety and good government of that society, and that that art and architecture which came after these qualities began to fall into disuse, however technically skillful, betray the ever-increasing emptiness and wickedness of the society that in turn produced it. Having never read Ruskin but only knew his reputation, I had expected him to be more of the prissy, phelgmatic type of scholar-author, who is generally resigned to unending cultural rot as the fate of the species and consoles himself with classical art and imported delicacies and wines. His style however is actually rather angry, and his book takes its inspiration at least as much from the contempt that is aroused in him by pretty much every development of the previous 400 years of history, and the worthless people who promote and accede to it, as from his love of the higher beauties to which he is trying to call our attention.

I made reference above to the difficulty I had in finding a complete, or "official text" of this book. It was orignally published, as far as I can tell, in three volumes in 1851, when Ruskin was 32 years old; while most authorities seem to consider this original work as worth reading in whole it is not readily available in any edition that I have found. It seems that there may have been a reprint of this edition a few years back--there is some fairly recent (i.e., post-1960) multi-volume edition--but what copies were available for sale on the Internet were $300 and up. Ruskin did at least one major revision, in 1879, in which large sections of the original book, particularly the third volume, were eliminated. There was another edition put out in 1900, a reprint of which, numbering 582 pages plus an index, was the version that I read, plus an additional 10 pages that were reprinted in the Norton Anthology of English literature that appeared in the 1851 edition but apparently did not make the cut for the 1900 edition. The New Hampshire State Library, which is a remarkable institution and resource right in my town that I stumbled upon by accident after I had already been living here some time, has a twenty-volume set of Ruskin's works from the late 1800s which includes a version of this book which seems to include several chapters which also did not make it into my edition. However, books older than the very arbitrary age of 100 years do not circulate (this is becoming increasingly unfortunate, as they appear to have been especially vigorous in building up their collection during the 1900-1910 period) and I do not have the time to sit in their reading room, though it would certainly be pleasant to do so (this building is all circa-1900 marble and porcelain and quartersawn oak and sycamore), and go through it. I did not find much of it scanned on the Internet either. So I have not read the entire book at least as it once existed but as much of it as I could cobble together.

Ruskin of course is more famous nowadays in some circles for his sexual problems than for his writing. The oft-repeated story that he froze in terror at the sight of his wife's pubic hair on their wedding night because he had expected it to bear a more exact resemblance to classical marble statuary is fiercely refuted by the majority of the most respectable scholars on the subject, but that this marriage was annulled after six years on the grounds that it had never been consummated is a matter of no dispute at all. His wife, Effie, who was "considered a great beauty", proceeded to marry the painter Millais (who painted the portrait above of Ruskin, incidentally), with whom, one book I have or once read which I cannot find now assures its readers, she went on to enjoy healthy sexual relations. Ruskin then fell desperately in love with a 9-year girl, to whom he unsuccessfully proposed marriage when she turned 18 (he would then have been about 50). He was also infatuated for a time with the teenage Alice Liddell, the daughter of the famous Greek lexicographer, and Lewis Carroll's very same Alice, a few years older (she must really have been something else). If he ever molested these girls rather than merely adored them hopelessly from a (psychological) distance, the historians do not seem to have any definite evidence of it. He is recorded as having suffered recurrent mental breakdowns over the last 30 years of his life.

Ruskin of course is more famous nowadays in some circles for his sexual problems than for his writing. The oft-repeated story that he froze in terror at the sight of his wife's pubic hair on their wedding night because he had expected it to bear a more exact resemblance to classical marble statuary is fiercely refuted by the majority of the most respectable scholars on the subject, but that this marriage was annulled after six years on the grounds that it had never been consummated is a matter of no dispute at all. His wife, Effie, who was "considered a great beauty", proceeded to marry the painter Millais (who painted the portrait above of Ruskin, incidentally), with whom, one book I have or once read which I cannot find now assures its readers, she went on to enjoy healthy sexual relations. Ruskin then fell desperately in love with a 9-year girl, to whom he unsuccessfully proposed marriage when she turned 18 (he would then have been about 50). He was also infatuated for a time with the teenage Alice Liddell, the daughter of the famous Greek lexicographer, and Lewis Carroll's very same Alice, a few years older (she must really have been something else). If he ever molested these girls rather than merely adored them hopelessly from a (psychological) distance, the historians do not seem to have any definite evidence of it. He is recorded as having suffered recurrent mental breakdowns over the last 30 years of his life.This last little scene involving three famous and decidly brilliant and interesting people (and members of their immediate family) who were on what we would call the faculty at Oxford University at the time, I want to comment a little on the intellectual environment which flourished in Oxford during the high Victorian period, from the 1860s to 1880s. We are left, it is true, mostly with the record of the most entertaining anecdotes and personalities, the most brilliant writings and advancements to human knowledge that were attained in the age, and the most stirring monuments to contemplate; the constants of university life such as pedants imprisoned rather than liberated by their knowledge, the lack of appropriate curiosity towards and work in certain subjects (Indian and Eastern Studies generally, technology, in this age--who knows what it will turn out to be in ours?) that have been leveled at the English Universities of this time by modern scholars, the stifling tediousness of official intellectual life imposed by the supposedly outdated traditions and program of study (i.e. unimaginative emphasis on classics) do not always recur so readily to the romantic's imagination. It appears to me however to have been a pretty lively atmosphere, in which what are broadly known as the Humanities carried a great deal of meaning and force to people possessed of the imagination and intellectual strength to make a world out of them. The students of this period tended I think to look back on their college days with more unequivocal fondness and to acknowledge the influence of their tutors deeper into life that at any other period in English history. Among the students at Oxford in this period who later wrote with affection of the place (an affection that other generations were more inclined to temper a little) were Oscar Wilde, the poet Housman, Max Beerbohm; I suppose Arnold and his friend Clough were a little earlier but the beautiful poem set in Oxford, "Thyrsis" (this is actually one of my all-time 10 or 15 favorite poems) was published in 1867 amidst this general mood. Besides the three mentioned above, famous teachers of the time included Wilde's guru Walter Pater and the famous Platonist Ben Jowett (I think the now-eclipsed Cornford may have been there too). Jowett was apparently a great prig but the spirit and acuity of the student body at the time was able to succeed in turning his lasting reputation into that of a quasi-ridiculous figure. I sure there are even better examples but offhand I cannot think of them.

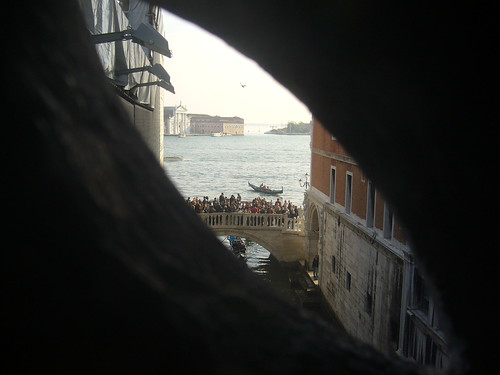

As the quotes in this book are of such a provocative and interesting nature that they stand alone well, and also as they provide a good overview of a subject--the rise and decline of the Venetian Republic as visible through its arts--that I think is not well known, I think I will just print the ones I like the best as they are, accompany them with illustrations if that can be managed, and comment on the quotes if I feel moved to. Here is what I wrote back on January 23:

As the quotes in this book are of such a provocative and interesting nature that they stand alone well, and also as they provide a good overview of a subject--the rise and decline of the Venetian Republic as visible through its arts--that I think is not well known, I think I will just print the ones I like the best as they are, accompany them with illustrations if that can be managed, and comment on the quotes if I feel moved to. Here is what I wrote back on January 23:

...His arguments are so unique as to be persuasive taken on his precise terms. Obviously his apparently fervent religious feeling which is the basis for much of his thought does not have much resonance w/us (sic. who do I mean by us?); also his classism. Nonetheless as a critic of art & architecture--the objects themselves--he is suberb.