The next part of the book which obviously begged for some comment was the incident the author described while living in Trenton during the war where he was refused service in a restaurant and threw a glass mug in the general direction of the waitress's head (for which he managed to avoid getting arrested). I grew up near enough to this town, which is very rarely featured in the world's literature, to have some familiarity with what it looks like, the type of buildings and restaurants and people it has, or would have had in the 1940s, and so on. The author observes several times that this sort of discrimination "in bars, bowling alleys, diners, places to live" was common throughout New Jersey at the time--noticeably worse than New York City, apparently. I do not doubt that this was the case, though as northerners are accustomed to think of this sort of blatant refusal of public establishments to serve black people together with whites as a southern phenomenon, I admit to have been taken aback for just a moment. I certainly knew that whites and blacks--as well as Jews and gentiles--did not for the most part frequent the same public spaces at all, and that anyone from outside one or another of the groups' intruding upon foreign turf would have been deliberately made to feel unwelcome; but the type of confrontational incident related in this story is never talked about as having been a fact of life, by white people anyway, in this area of the world. Indeed, it may not have been a common occurrence, for the general feeling seems to be that these arrangements were "understood" and adhered to by pretty much everyone apparently without thinking or worrying too much about it.

Most of my reactions to the Trenton story were colored of course by my own sympathies combined with my awareness that the author knows he is writing for a predominantly white audience--writing, in fact much more to the likes of me than Evelyn Waugh or Marcel Proust ever intended to write to such likes--about his desire to wring the neck of his waitress, a white girl with "great, astounded, frightened eyes", just description enough to plant the idea in our heads that she isn't some wholly discreditable fat, cretinous white girl that we can gladly join him in despising but somebody who might be cute enough to really desire to protect from the violence of this raging black man. "She did not ask me what I wanted, but repeated, as though she had learned it somewhere, 'We don't serve Negroes here.' She did not say it with the blunt, derisive hostility to which I had grown so accustomed, but, rather, with a note of apology in her voice, and fear. This made me colder and more murderous than ever." (emph. mine). (I also could not refrain several times from noting my astonishment at his being in a crowd where "everyone was white" or coming to "an enormous, glittering and fashionable restaurant" with the comment "in Trenton?!", which incongruities with one's own experience I have a bad habit of always finding slightly humorous even if the larger context within which the meaning of the amusement lies is not funny.) The point, I believe, is that he was driven to this undignified and dishonorable behavior (throwing the mug) by the circumstance that the world around him continually denied him any opportunity to be--or certainly to feel and appear--dignified, which last was of exceeding importance to James Baldwin, as it is to most people of course, but he was not the sort of artist who infuses a distinctly singular and self-contained relation to life into his work. Or as I wrote back on January 22:

--Baldwin has lots of good material and is pretty perceptive but there is always something a little off in his composition and general style. I don't know that he ever nails/achieves his own voice and molds it into the cast of literature. The incidents don't come together to make a coherent impression of the man's self...he has not the high mastery over the world that enables him to take in a whole picture. He remains unrealized--overaware--

"Racial tensions throughout this country were exacerbated during the early years of the war, partly because the labor market brought together hundreds of thousands of ill-prepared people, and partly because Negro soldiers, regardless of where they were born, received their military training in the south." James Baldwin himself seems not to have gotten drafted into the military; at least he doesn't mention it.

"It would have demanded an unquestioning patriotism, happily as uncommon in this country as it is undesirable, for these people not to have been disturbed by the bitter letters they received, by the newspaper stories they read, not to have been enraged by the posters, then to be found all over New York, which described the Japanese as 'yellow-bellied Japs'." I include some of these quotes because it seems to have gone widely unremarked during the hyping of the current military situation, in which the devoted patriotism, courage and devotion to the armed forces of the American people during World War II was continually extolled to shame the modern generation, that a great deal of the letters and books which were produced during and about the period, by white as well as black authors who were actually there, are pretty negative in tone, especially where Army life was concerned. Obviously there are the big names, Heller, Vonnegut, James Jones, Mailer, even Herman Wouk, among whom the consensus seemed to be that the military establishment was either insane, sadistic, incompetent, or some combination of the three (and the books about the British army in World War II paint an even more wretched picture--so much so that one assumes the accounts must be gravely exaggerated, but that is a matter for another time). But even such letters as survive from my grandfather and uncles written from the front are pretty grouchy--complaints about bad coffee and having to eat mutton for weeks on end (my grandfather spent a lot of time in England) seem to predominate--there was certainly no sense of poetry or excitement. My grandfather, who was a Catholic and not a bookish man at all, regarded England as little more than a sort of giant toilet until the day he died and thought it ridiculous when I would say I dreamed of visiting it someday. I guess the point is that they bothered to show up, they didn't shirk their duty, and the national goals were in very large part able to be achieved, which increasingly it looks like is not going to be the case in our own generation.

"It was the Lord who knew of the impossibility every parent in that room faced; how to prepare the child for the day when the child would be despised and how to create in the child--by what means?--a stronger antidote to this poison than one had found for oneself.."

I should have noted that the whole of the essay "Notes of a Native Son" centers around the events of the day of August 3, 1943, which besides being Baldwin's 19th birthday, was also the day of his father's funeral, as well as the day on which a big race riot had broken out in Harlem.

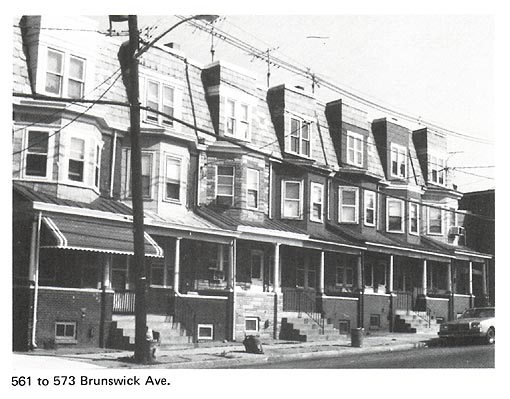

I had attempted to put up a picture--a stolen picture, let us make no mistake--of some Trenton rowhouses circa 1940 here. I confess I am so desperate to sex up my blog in any way possible and attract attention that I do steal pictures without authorization a lot.

I had attempted to put up a picture--a stolen picture, let us make no mistake--of some Trenton rowhouses circa 1940 here. I confess I am so desperate to sex up my blog in any way possible and attract attention that I do steal pictures without authorization a lot.

2 comments:

Dude, you've grown so laconic in your old age I hardly recognized you...

Paul Eskey

Thanks for writing. I am sure it really is Paul Eskey, too. The manner of expression is wholly authentic. I imagine the thought at least as pure spontaneous effusion. I never have thoughts of pure spontaneous effusion, so I am very keen when it comes to recognizing them in others.

Post a Comment