Love them and extol them as my favorite era in cinematic history though I do, I actually have not even seen that many of the classic films of these years. Today's group includes three I had never heard of previously and another that I had confused with something else. So I was pretty excited at the likelihood of discovering at least one unsuspected pleasure in the bunch, which kinds of pleasant surprises of course grow more infrequent with the inexorable advance of age.

The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

This is the one I had confused, thinking of Blackboard Jungle, the famous film about 50s juvenile delinquents who came to school chewing gum, flashing switchblades, and generally not bearing a mindset conducive to effective learning (Thank goodness we have gotten those problems under control). The one is a film noir directed by the legendary John Huston, with whose work however I am just beginning to become acquainted. Indeed I am just starting to distinguish his career from that of fellow legend (and John) John Ford, with whose work I am even less familiar, though the latter's legend is if anything even bigger at the highest levels of cinephilia than Huston's is--doubtless at this very moment some avant-garde Japanese director with pink hair that I have never heard of is declaring with complete sincerity that John Ford is one of the major influences on his work. Back to Huston, last year I watched and reported briefly on The African Queen, which came out the year after this, and which I was entertained but not much absorbed by. Some years ago I saw 1948's Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which I remember, albeit hazily, as more substantial, and probably great. I also saw his 1987 version of Joyce's The Dead even more years ago, which at the time however did not strike me as adding anything to the original story. My feelings on The Asphalt Jungle are again somewhat mixed--I have yet to make that connection with Huston's peculiar vision, or genius, that makes one an especially devoted admirer.

As noted, The Asphalt Jungle is another film noir, of which genre we have been on a bit of a run these past few years. Huston also made The Maltese Falcon and Key Largo, which I have not seen but which I take to be in the film noir spirit, though as they featured actors who were A-list stars at the time and had bigger budgets and promotion they are sometimes not included among the classic B-movie, harshly lit, ugly mug strain of classic film noir. This one had lots of ugly mugs and no established superstars (though it did feature several people who later on became stars, including, most notably, Marilyn Monroe), so it is often considered the most purely noir picture Huston made. Film noir story arcs all being largely the same, the style, characterization, idiosyncratic plot elements, sex appeal of the women, etc, etc, of this family of movies are especially important. These elements in Asphalt Jungle are not terrible, but they are not on the level of Double Indemnity or The Third Man, both of which have more evocative settings and sophisticated characters (and consequently dialogue), somewhat more developed criminal schemes, more interesting clothes and other props, as well as (to me) more appealing women. Of course both of those screenplays were written by celebrated literary authors (Raymond Chandler and Graham Green), a connection I had previously failed to make, and the significance of which clearly shows in these instances.

I have written before that I am not the greatest Marilyn Monroe fan who ever lived. She plays what most people would think of as a prototype Marilyn Monroe character in this movie. She is 23 or 24 here, and even I her detractor grant that she is eminently squeezable. There is nothing else in her persona here that particularly excites me however. The humor and warmth that she allegedly brought to her later celebrated roles is yet in evidence. She and the other main female character, played by Jean Hagen, are perhaps illustrative of a general transition in the depiction of womanhood as the 40s moved into the 50s, certainly in the realm of film noir. Both of the women in this are rather passive, weak and stupid compared to their mid-40s noir counterparts, either the famed femme fatales, who were hard, scheming, usually unsentimental agents of destruction, or, if they were virtuous, intelligent and forceful enough to assert their personalities with some effect against the evil that threatens to engulf them on all sides. The change I am describing is probably exaggerated here--from what I have seen and heard of Huston, he was a man's man whose genius did not lie in his depictions of women or male/female relations--but I most people have always sensed that something of the sort did broadly occur.

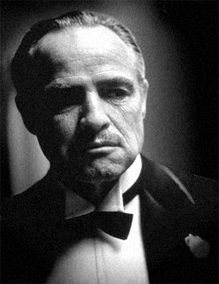

I have written before that I am not the greatest Marilyn Monroe fan who ever lived. She plays what most people would think of as a prototype Marilyn Monroe character in this movie. She is 23 or 24 here, and even I her detractor grant that she is eminently squeezable. There is nothing else in her persona here that particularly excites me however. The humor and warmth that she allegedly brought to her later celebrated roles is yet in evidence. She and the other main female character, played by Jean Hagen, are perhaps illustrative of a general transition in the depiction of womanhood as the 40s moved into the 50s, certainly in the realm of film noir. Both of the women in this are rather passive, weak and stupid compared to their mid-40s noir counterparts, either the famed femme fatales, who were hard, scheming, usually unsentimental agents of destruction, or, if they were virtuous, intelligent and forceful enough to assert their personalities with some effect against the evil that threatens to engulf them on all sides. The change I am describing is probably exaggerated here--from what I have seen and heard of Huston, he was a man's man whose genius did not lie in his depictions of women or male/female relations--but I most people have always sensed that something of the sort did broadly occur.Sterling Hayden, who I just saw recently further on in his career in The Godfather (he's the Irish cop who gets it in the Italian restaurant), was the lead in this. He was six foot five, which is unusually tall for a movie star. He's not one of my favorites either. It's not clear whether he is really kind of dense, or if he just got assigned to play a lot of dense characters. In any event, he played them perhaps a little more literally densely than was called for.

There is a trope in the movie that each of the characters in on the heist has a weakness that ultimately leads directly to his downfall. I thought this was a rather hokey element that didn't really add anything to the movie, especially the Sam Jaffe character, who is the mastermind of the operation but is supposed to be an incurable old lecher who gets mesmerized watching a girl dancing to a jukebox in the kind of roadside tavern I am always searching for in my own travels and ending up shuffling into Friendly's twenty minutes before closing time after several fruitless hours of searching. I am coming off as down on the movie, but it has its good points, and it is fun to talk about. It did not grab me as great however.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943)

I am going a little out of order due to the way the pictures arranged themselves in the loading.

There is a considerable amount of awesomeness in the myriad parts of this movie, which, if they do not perfectly cohere into a completely staggering whole, still make for a uniquely great film after a manner. This was made in the midst of the war and is nominally a propaganda movie, but it is more sophisticated than the usual specimens of that genre. Colonel Blimp was a newspaper caricature which was supposed to represent the chauvinistic, tiger-hunting, war and empire-loving, intellectually obtuse, conservative element of society whose attitudes were relics of the increasingly remote Victorian era--i.e., he was not conceived with flattery in mind. The irrepressible, up to date, and rather brilliant filmmaking duo of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, whose work I am encountering for the first time, decided to make this restless and generally likeable (at least to people with some affection for the old British ruling classes), though frequently clueless creature the hero of their wartime epic; and it worked. The story, after a jazzy opening sequence in the (1943) present which is repeated and clarified at the end of the movie, finds the aged though still commisioned Colonel Blimp (who actually is a general and is named Clive Candy in the film) in the Turkish bath at his London club, where in the midst of a tussle with a young whippersnapper who has come to play a prank on him, we are transported back to the same scene 40 years earlier, when Blimp is a dashing young officer. Colonel Blimp, by the way, is played by the superb actor Roger Livesey, who was apparently a last second replacement for Laurence Olivier. Olivier's presence is not missed, which should give an idea of how good Roger Livesey is. We then follow Blimp/Candy through the ensuing forty years, which include numerous scenes of interest including a rollicking beer hall and a duel in imperial Germany, an abbey in World War I France, a dinner party at Blimp's house in 1919 with a (now) ridiculous gallery of pompous guests with important titles, and a visit to the underground bunker housing the BBC's wartime studios. Gaps, or, as Christopher Fry more elegantly put it in one of the bonus materials, lacunae, in the story, usually the periods between wars, are marked by a striking device which is remarked upon by every commentator on the film, in which the heads of the victims of Blimp's hunting expeditions throughout the British Empire appear, following the sound of a rifle shot, mounted upon the wall in his study, accompanied by a placard with the name of the country and the year of the kill. The study was actually looking like a pretty cool place to hang out by the latter stages of the movie.

This is a Criterion Collection film, and as such features a pretty good commentary, by Martin Scorcese and Michael Powell, the director of the picture himself. Powell died in 1990 at age 84, so his portion was evidently recorded some time back. He sounds quite aged in it. Scorcese's part is a little too film geekish for me, but Powell's is most enjoyable. Though he refers to his origins as middle class several times in the course of the monologue, he comes across as one of those old timers who was deeply educated and immersed in the European art tradition from an early age--perhaps that is an upper middle class signifier. While there is some technical movie directing talk, he also talks a lot about his Savile Row tailor, the fashions in ladies' hats through the early part of the 20th century, the etiquette of duelling in Germany, and things like that. When discussing actors, he noted that Deborah Kerr (pronounced "car") was intelligent, which was unusual in that profession. He did not say this in a perjorative way however, as we have being accustomed to take such statements, but as if there were numerous qualities of equal value that a good actor, or a good person, could possess. He clearly held the abilities of Richard Livesey, to whom he attributed the quality of unusual honesty, in high regard, though he did not praise him as intelligent, this the more pointedly as the discussion of his honesty came within five minutes of the comment about actors generally not being intelligent. There is a part at the end where he lucidly explains the impressiveness with which the Austrian actor and refugee from Nazism Anton Walbrook--I can't believe he wasn't intelligent--carries off a long speech, in English, a foreign language for him and in a different tradition, which makes Scorcese's and all contemporary people's gushings and conversation on interesting matters seem utterly inarticulate.

This movie was made in gorgeous Technicolor. On one of my old posts I wrote that I had never seen a British film in color prior to 1965 or so, and was only aware of the 1951 festival-commissioned The Magic Box, which for some reason is not available in North America, as having been shot in it. Evidently British Technicolor films constitute an entire genre of cinephile fetishism. Scorcese, in the most interesting observation he made on the movie, noted that British Technicolor films were widely considered more beautiful than Hollywood's offerings of the same, because the muting effects of the continually overcast English light made for a more delicate and striking effect, and after seeing this, I am inclined to believe him. Why don't they make movies in Technicolor anymore? Is it expensive? Because when done well, it looks better than whatever kind of color treatment is usually used now.

Deborah Kerr, best known among us for such 50s Hollywood classics as From Here to Eternity, The King and I, and An Affair to Remember, was, for lack of a better word--I am too tired to come up with one at the moment--a revelation to me in this movie. She played three different girls, one in 1902, one in 1918-19, and one in 1943. Her 1919 persona was pretty fetching--I like the style of that time too--but the 1943 version of her as Colonel Blimp's driver just about laid me out. It's the hair. There is no amount of exposure to 1943-44 women's hairstyles that is possible to weary me of them--and if you can believe it there are many creditable people who think those were the absolute worst years for women's hair in the whole 20th century!