BBC television production, in glorious black and white. Though I was taken enough with the whole effort, the highlight was the epically gorgeous 1967 hairdos worn by the lead actresses, who were both named Angela*; which hairstyles, imaginatively at least, translated well to the 1840s. One of the Angelas played Cathy Earnshaw as a brunette in the first two parts of the series, and Cathy Linton (the first Cathy's daughter; the mother of course died in childbirth) as a blonde in the last two. The other Angela played Isabella. The male leads were decent enough too, I guess, especially the guy who played Hindley was good. Ian McShane, who is something of a name, was Heathcliff. He did not to my mind emit to the full the masculine ferocity that this character so famously and belovedly exhibits in the book, though it does not seem as if anyone has managed to capture that on the screen (I have not seen the Olivier version, but supposedly he is an even milder Heathcliff than McShane). The sets and outdoor camerawork are simple but evocative, and one never feels that something would have been better if more money had been spent. Once again it is demonstrated that a little atmosphere, a few good-looking girls, supporting players with some presence and a good story can go a long way.

Regarding the story--like the Idiot, this is in my opinion one of the great stories of the post-renaissance era. It always works for me. I had the good fortune to read the book at a pretty young age, before I was fully cognizant of my mind's inability to keep up with my ambitions for it--it was the very first book I took up when I started reading again after I had been out of college for a while--so I remember it quite well. It is extremely funny, and all of the characters have either well above average verbal intelligence irrespective of their stations, or are so freakishly absurd in some way that their presence serves to stimulate rather than stifle the more intelligent characters. I think that the book resonates with as many people as it does because it does have all of this humor and intelligence while taking place far out of the way of great events or anything resembling intellectual ferment or heightened social stimulation or even economic and societal churn. To recreate this type of scene would seem to be more attainable to the socially isolated modern reader than those found in other books which either require extraordinary talents, years of high level training, or even generations of cultural indoctrination as their basis. Also, the characters that possess no inconsiderable amount of sex appeal (and any amount is not inconsiderable to me)--even Heathcliff--are not exactly surrounded by people equipped to properly appreciate and quench it, which does have the effect I suppose that its edge is never wholly dulled. I suspect a lot of people imagine this to be the case with themselves too and sympathize with the circumstance in the book.

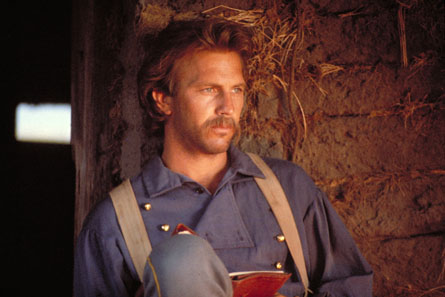

Angela Scoular as Cathy Earnshaw (with Heathcliff)

*I have always liked the name Angela a lot and have brought it up as a possible baby name but my wife always immediately shoots it down as having trailer park-ish conntations for her. Perhaps this is more the case around here (New England). In the suburban mid-Atlantic area in which I grew up, I associate it more with energetic, slyly nice but maybe also slyly naughty daughter of an orthodontist types. My idea of trailer park names falls more in the direction of Crystal, Brenda, Tammy, and the like, though I associate Tammy as being usually the good-looking one from this pool and therefore have some fondness for that name as well.

The Report on the Party and the Guests (1966)

This is a somewhat hard movie to find. I ended up doing something I don't usually do, which is shell out for a four-DVD Criterion Collection set of "Pearls of the Czech New Wave", which includes six movies from 1966-69, one feature by each of five different directors, plus one collective effort in which each the featured directors contributed a short movie based on a story by the important and very good Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal. The Report on the Party and the Guests is only 70 minutes long, so I watched it twice. I don't think it is a great movie, but one has to grant that it took some cojones to make it (and I would think to be involved with it at all) in 1966 Czechoslovakia. The plot is that a group of vaguely bourgeois adults out on a picnic in a place that looks like it could be the Sumava forest are surrounded while strolling through the woods by a large band of unfriendly men who do not pointedly hurt or even threaten the picnickers but nonetheless make it clear that their movements are restricted, that they will not be allowed to leave the area, that they will have to submit henceforward to the authority of the men who have interrupted their walk; apart from a few weak and half-hearted attempts at protest and rebellion, the picnickers accede and become resigned to their new condition relatively quickly. In the second half of the movie they are brought to a large outdoor banquet like a wedding dinner along the wooded shore of a lake, and a number of odd things happen--for example, the guests all realize they are not sitting in their assigned places at one point and move en masse to find them. The meaning of a lot of what went on the second part admittedly was not clear to me. One of the picnickers, who had remained silent and sullen, does slip away from the table during the banquet; a search party is raised to go bring him back, and his wife (who is kind of attractive in a matronly late 30s way, but does not possess much character to oppose any convention or authority) apologizes to the leader for his antisocial behavior. Another picnicker, flattered by the new authorities' assurances that he is a reasonable and intelligent man, spends the banquet trying to ingratiate himself with them. As happens to me a lot with Czech movies, something will appear on the screen--some kind of food or utensil or mannerism or even the odd word or phrase which I can still pick out--which reminds me of when I was there and sends me into a reverie which distracts me from following the movie. Still, on the whole, I have a much easier time getting into these Czech New Wave movies than I do the likes of Godard and some of the other French avant-gardistes, even when the narrative does not take an easily-deciphered form, because I feel I have some sense of at least the material world these movies inhabit. Also even the most talented Czech artists--and this seems to extend even to major international figures such as Dvorak or Smetana--tend to see themselves and their countrymen more as underdogs and subversives trying to cut a few slivers through the massive quantity of baloney weighing people down to expose any fleeting flash of truth than as people in a position to make grand pronouncements and discoveries about the state of civilization or the nature of universal man that will take the average person a few generations to catch up to and absorb anyway.

When the picnickers are first taken into power by the mysterious band their leader is a rather clownish guy who looks and kind of behaves exactly like Adam Sandler. Eventually a more distinguished gentleman shows up to conduct the captives to the party who is revealed as the real leader.

The Adam Sandler Guy

The women in all of these films are variously quite attractive without being classically movie star beautiful. In this one they all seem to be in the 32-37 range for age--of course that is young to me now. I have gotten to the point where I at least am finding some 32 year olds as beautiful as I once thought women ten to fifteen years younger to be. Anyway these are the kind of women I imagined I would have hung out with a lot if I had ever been able to establish my artsy credentials. Of course our imagination always outstrips reality. As I have written before, I imagined myself before I went to college hanging out with women of a certain type that I thought, and congratulated myself for thinking, reasonably realistic, whom I found upon arriving at school barely existed at all, and when they did had far more desirable social and physical options than I could offer at the time.

The Women I Found Attractive Despite Their Being Rather Weak and Stupid in the Movie

I have watched a couple of the other films in the collection. The first was Pearls of the Deep, which is the collection of shorts based on the Hrabal stories. It is a superb mixture of quirky Hrabal stories, imaginative and beautiful film-making, and documentation of the Czech life and personality. The directors were Jiri Manzel (Closely Watched Trains), Jan Nemecs (The Report on the Party and the Guests), Evald Schorm, Vera Chytylova (Daisies), and Jaromil Jires. If I had to rate the shorts, I would say Schorm's ("The House of Joy") about a butcher and amateur artist who covered every bare surface in his house with his painting, is the most interesting idea, Chytylova's (The Restaurant The World) is the most cinematically arresting, Jires's ("Romance") the most evocative of what it is like to be out and about in Prague. Menzel's ("Mr Baltazar's Death") is also very good--I wonder if it was not the most effective as a literary story--and had many ingenious images and directions that it took. The Nemec ("The Imposters") was good too, though the simplest and most straightforward of the set. I also saw the somewhat famous Daisies, which I liked for a while but of which I eventually grew a little tired. In its story of two anarchic girls running wild, rejecting conventional romance and other girlish concerns, cutting up penis-shaped fruits and meats, putting old men on trains they don't want to be on, and smearing food and various other things all over their beautiful young bodies, I was reminded a lot of Celine and Julie Go Boating. How much was I reminded of it you say?

Sedmikrasky (1966)

Celine et Julie Vont en Bateau (1974)

Quite a few other people on the internet have noted the similarities between these two films. It is not my special insight.

At one point of the girl's names in Daisies was Julie too, but their names kept changing.

The Adam Sandler guy was briefly in this also, as a hopeless sap in love with the more extreme 60s chick of the duo, the one with the rust-colored hair. I thought they were both sexy, but I suppose if I had to pick I have a slight preference for the brunette.